Transcript: Adam Tooze at CCG

June 30 , 2025

Columbia University’s Adam Tooze delivers keynote and interacts with audience on green transition and China’s influence in Beijing

On June 30, 2025, Adam Tooze, Shelby Cullom Davis chair of History at Columbia University, Director of its European Institute, and renowned author of the Chartbook newsletter, visited the Center for China and Globalization (CCG) in Beijing for keynote speech, a dialogue with CCG Founder and President Henry Huiyao Wang, and a Q&A session with a live audience.

A full transcript of the discussion, based on the video recording, is made available here. Please note that the transcript has not been reviewed by any of the speakers.

Good afternoon. My name is Wang Zichen. I’m a Research Fellow and Director for International Communications at the Centre for China and Globalisation (CCG). So, welcome everyone. We are very glad to have Professor Adam Tooze with us this afternoon. Let me just give you what’s going to happen. He will give a presentation, after which he will engage in a conversation with Henry Huiyao Wang, the founder and president of CCG, and after that, he’s happy to answer questions from the live audience. We expect the event to last for maybe a little bit longer than an hour.

So, without further ado, let me give what I believe to be a comprehensive introduction to my friend, Adam. Adam—I mean, he can go anywhere without an introduction—but he is one of the most influential historians and economic thinkers of his generation, renowned for his penetrating analysis of the forces that have shaped and continue to shape the modern world.

As a Chair Professor of History at Columbia University and Director of its European Institute, Adam’s scholarship and public commentary span global finance, geopolitics, war, and systemic crisis, making him a vital interpreter of both history and contemporary affairs. Tooze has a PhD, I believe, from the London School of Economics. He taught at the University of Cambridge and later at Yale, before joining Columbia’s faculty. He also serves as the Director of the European Institute there.

He is the author of quite a few books, many of which have won the leading awards in the world, including The Wages of Destruction, Crashed, and Shutdown: How COVID Shook the World’s Economy, which was published in 2021 and chronicled the unprecedented economic and political disruptions over the COVID-19 pandemic.

Beyond academia, Tooze has emerged as a leading public intellectual, sought out by policymakers, journalists, and the public for his clear-eyed analysis of global economic and political trends. He also writes—as I believe many of you subscribe to Chartbook, a widely followed newsletter on Substack launched in 2021, where he publishes essays, data-rich analysis, and timely commentaries on subjects ranging from inflation and central banking to climate finance and geopolitical risks. Chartbook has become essential reading for those seeking to understand the structural drivers of crisis in real time. And as many of the Chinese audience here understand, there is actually now a Chinese version of Chartbook available on WeChat. So check it out if you haven’t.

Tooze is also the co-host of Ones and Tooze, a popular podcast produced by Foreign Policy magazine, where he engages with whom I believe to be a deputy editor of the journal. I had the opportunity to attend one of your live recording sessions in New York City, I think, last year. So, each episode there explores a major story and a single illuminating statistic, offering accessible yet sophisticated discussions on topics like European energy shocks, emerging market debt, or the geopolitics of green transitions.

As a contributing writer for Foreign Policy and a frequent columnist for The Financial Times, The Guardian, The New York Times, and other major publications, Adam regularly provides incisive commentary on global economic governance, monetary policy, geopolitical conflict, and climate-related risks. His columns are widely cited and have influenced debates on how institutions, from the Federal Reserve to the European Central Bank, navigate crises.

I think we are all big fans of Adam. His unique strength lies in his ability to place today’s events in a historical and systemic context, helping audiences grasp not just what is happening, but why it matters. His interviews, commentaries, and public talks appear in major media outlets such as Bloomberg, BBC, CNN, and NPR. I think he’s here in China this time for the World Economic Forum in Davos, and he also spends a few more days in Beijing.

So, we are truly honoured to have Professor Adam Tooze come to CCG. And so, Adam, you’re welcome to come to the podium and share with us this crucial topic that everyone is talking about—not just in China, but also across the world—which is “The Global Green Transition and China’s Role: A Historical Perspective.” Thank you.

It is easy, when talking about China’s industrial development, to fall into a sense of hyperbole—that we may, in some senses, be exaggerating what’s going on. But in this particular case, there is, in fact, a need to, in a sense, restate the hyperbole.

One of the challenges of thinking about China’s economic development—material economic development, especially the energy side of China’s economic development—is whether or not we can in fact, whether we have the terms, and whether we have the historical experience large enough to do justice to the radicalism as what has happened, and therefore also the challenges that lie ahead.

And part of my mission, as I see myself, in intervening in Western conversations in the current moment, especially on what you might call the progressive side of climate politics in the West, is to bring home the scale and the drama of what needs to happen and what will be driven by the Chinese side—what, in fact, is already being driven.

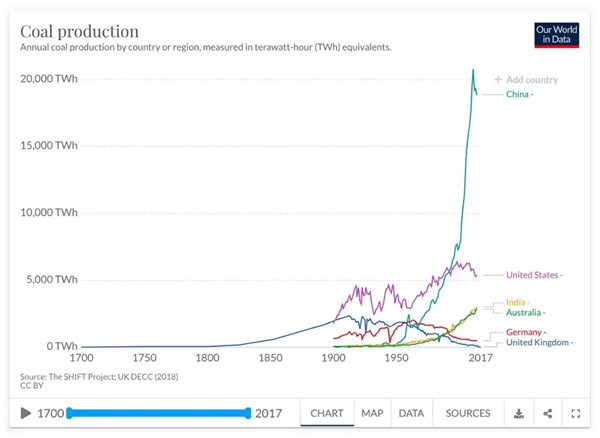

And what this requires us to do is, if you like, to pinch ourselves. This graph, which comes from Our World in Data—a very familiar source—is as staggering a graph as I could possibly put on this board, and we look at it and just go, “Oh yeah, well, that’s what we know what’s going on.” This is coal production in recorded human history. This is species being, in the Marxian sense—all humans who’ve ever lived. This is how much coal they have ever mined. And I don’t need to tell you, but coal is a really good proxy for modern urban industrial development. Without it, no Industrial Revolution, no industrial capitalism, no fully organic surplus value production and exploitation, as Marxian texts laid it out in the 19th century.

If you use this metric, it is impossible to avoid the conclusion that the history of our species on the planet—I do not exaggerate, this is all the numbers there are; there’s not some other bit of unrecorded energy history out there that isn’t captured here—it falls into three phases. The phase up to 1750, where human societies relied largely on a somatic, biological energy regime—firewood, human power, animal power. The period between 1750 and the end of the 20th century, which was the classic industrial regime, started by the British, copied by the Germans, the Americans, the Japanese, the Soviet Union, by China in the phase of development in the ’50s and ’60s.

What we take to be industrialism and what, crucially for our purposes today, climate politics at a global level was framed around in the 1980s and 1990s, when we thought we knew what the climate problem was. And it was American-centred. It was Exxon. It was Texas. It was Europe. It was Krupp. It was the Ruhr. It was Europe. It was Western industrial history.

And the third phase in the history of global economic development starts within, I think, literally all of our lifetimes. Everyone in this room is old enough to be part of this history, because it starts almost on the dot of 2000. And it is this explosive curve here.

Again, let me just re-emphasise: there’s no “out here.” There’s no other bit of history we haven’t considered. This is all of fossil fuel history as summarised by the coal variable, and you can see what China did to that history in the last 25 years. It’s a sudden, utterly radical break with all previous human history. It’s a break with China’s previous history. China had heavy industrial development in the Mao period, which was heavy; it was large; it was incredibly inefficient. In the early phase of opening up and reform under Deng Xiaoping, there were two radical policies: one-child policy, and the other radical policy was energy efficiency.

So, in that period, China grows without exploding the fossil fuel envelope through the late 1990s. And then, within all our lifetimes, something completely mind-blowing begins to happen in China. It shocks the Chinese government apparatus itself. No one can really keep up, and we see this huge explosion in coal consumption and production, which is literally unlike all previous recorded human history.

This is one dimension of it, but it’s also true for steel. It’s also true for cement. And it’s what we see all around us. It is, the West will often say, driven by exports to Europe and the U.S. You all know that’s nonsense. That’s maybe 10 to 15 per cent of the Chinese growth. Most of it is Chinese urbanisation. It is the building of buildings like this—the one that we’re currently under. Zichen was telling me this is a building that came from the ’80s–’90s period. It is the construction of China’s massive new cities, the urbanisation of new migrants—of 500 million people—and the modernisation of the entire Chinese housing stock in the course of 30 years.

One of the most staggering numbers—those of you who know me know how much I carry this close to my heart—that it was in an IMF report: almost 90% of the apartments that Chinese people live in today, all of you lived in and grew up in, were built since 1990. As a European, that’s unimaginable. I’ve actually barely ever lived in anything that was built after 1990 in my whole life. In China, everyone has lived in a churned, remade fabric. And the basic argument of this paper—what I’m going to say—is that that changes the climate policy game.

Chinese climate policy in the 1980s and 1990s was formulated around this bit of fossil fuel history. It was a Western-centric story. It was an oil-centric story because it centred on the United States. It was largely the diagnosis of Western scientists of a global problem. It followed an incredibly classic stereotype of the formulation of global problems by Western intellectuals, which, in this case, they could also claim culpability for creating. You could argue—I would say—that the climate problem, as it was formulated at Rio and at Berlin and then in the Kyoto Protocols, was the last great Western cause. We did it. We diagnosed it. We have to save the world from the consequences of what we did and are still doing.

And what we are still coming to terms with is the consequences of what happened in China in the last 25 years, because that changes the game. It changes the game in a negative sense, you could say. It changes the game because it accelerates the climate crisis at an absolutely dramatic pace. But it changes the game also because it calls the bluff in thinking about development. China actually delivers on the promise of development. The West had talked about development for decades—China actually does it. And when it does it, even if its per capita emissions are at European rather than American levels, because 1.4 billion people are carried along by this process, it completely changes the geography, the geo-economics, of the climate story. And it makes China—whether comfortably or not, whether this is convenient for Beijing or not—the dominant player.

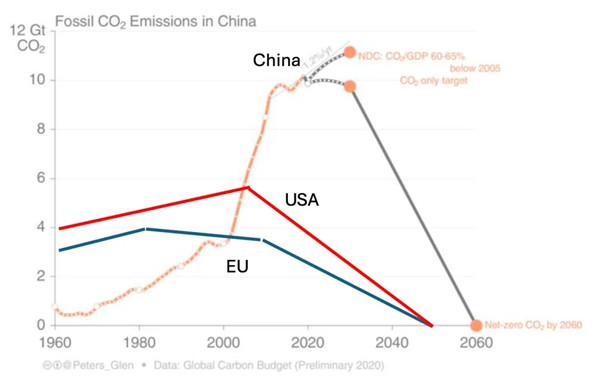

What I’m doing right now is actually writing a history of this moment. It’s really fascinating. All the way down to the late ’90s, climate politics in the world was conditioned on the expectation that China might never overtake America’s emissions. The most activist American business opinion argued that China would overtake America’s CO₂ emissions in the 2010s. In fact, China overtook America’s emissions in 2006, right? And from that moment onwards, it took time, but Beijing was faced with the increasingly awesome responsibility of realising that China is the decisive variable in climate politics going forward.

And that is the world, that is the history that we are dealing with. This is the dimension, I would argue, in which the overtaking of the West by Asia, and principally by Asia, has happened first, most dramatically. And we actually have to come to terms with this.

You will know that military technicians argue about when China will overtake the U.S., and economists argue about purchasing power parity and current dollars and so on, and we don’t know when China will overtake the U.S. But in climate politics, it happened 20 years ago. China’s electricity production today is two times America’s electricity production—twice. So there’s not an argument about the relative size of the economies as physical apparatuses.

So, 1990s climate policy followed a Western, U.S.-dominated energy history. It was oil-centric. Coal was relatively marginal. It was a Western transition model of climate policy that dominated, where it was about marginally tweaking downwards energy consumption away from fossil fuel towards less polluting sources. Policy tools that the Europeans and Americans pushed were largely negative—it was about carbon taxes, cap and trade, and all these kinds of things—and it fitted within a minimalist policy paradigm, which was neoliberal. The climate regime of the 1990s and the 2000s isn’t in contradiction to neoliberalism, I would argue, but is actually married at the hip. They’re joined at the hip in the West.

China destroys that paradigm. Its oil is secondary. Coal is absolutely dominant. Growth, not substitution, is the key dynamic. Carbon taxes, cap and trade are present, but secondary. Industrial policy is king, and it fits within China’s unique policy synthesis, which is clearly not easily assimilable to anything that we could call neoliberalism. And that, I think, is the reality that we are communicating about globally. And it’s really difficult to talk about this because it goes to such fundamental issues.

The scale of the challenge is spectacular. This is what I mean about the difference between the way in which the Europeans and the Americans think about the energy transition and the way in which China will have to go to bring about the energy transition.

Since my childhood, one of the most famous images for the energy transition in the West is steering an oil tanker. If you think about an oil tanker, it’s huge, it’s slow-moving, and you can only move it really gradually, right? China’s energy transition problem is like a race car—a huge race car, the biggest race car anyone’s ever seen—and we’re going to go like this, and then we’re going to swing it around and head it down like no one has ever seen. A physical process of transformation like the one that China is currently contemplating—it’s not the same problem as in the West.

This is the first thing, I think, to get our heads around, right? The drama of this graph here—it is such a different type of problem. It’s all about growth. It’s all about change. It’s not about slow substitution.

So, in the philosophy of history, we talk about Europe and the “end of history” hypothesis—Fukuyama, you will have heard of it. This, I would submit, is a Fukuyama-style energy transition: gradually, gradually, gradually, the Germans and the Dutch are going to persuade themselves to do things even more optimally and even more greenly, and they’ll recycle a little bit more, and then we’ll get to net zero and stability. That’s not China’s story. It’s drama from start to finish—huge urbanisation and then the most spectacular decarbonisation, if we’re actually serious about the promise of net zero by 2060. If you’re serious about that, the implications are utterly spectacular.

I would argue, in fact, that so far, the framing of the climate change problem from the perspective of the U.S. and Europe obscures not just one alternative but three alternative prospects that face the world, when we think about the energy transition not as the unipolar model of the ’80s and ’90s—the Bill Clintons, the John Kerrys of this world, or the Joschka Fischers in Germany. But if we think about it as a global proposition, we have four regimes, right?

We have the high per-capita energy consumption, low-growth world, which is where the problem was first conceived. We have the high per-capita energy consumption, high-growth world, and that’s China. At this point, per-capita energy consumption in China is at the same level as in much of Europe. There is no hiding place anymore. CO₂ emissions per ton per head of Chinese population is at a par with Germany and substantially higher than Britain, France, or Italy—obviously half the American level, but the American level is this obscene, special world of Canada, Australia, and the Gulf.

Then there is the Indian case, which is low per-capita emissions and high growth. Their question is: how do we change the direction of a growth path which is really rapid? And then there’s a billion people in Sub-Saharan Africa who, up to this point, don’t have a viable growth model and exist at incredibly low levels of energy consumption. And really, if we look forward to the next 30 to 40 years, the problem of the energy transition and global climate policy is the relationship between these four components. And that’s what I want to spend the rest of today’s talk talking about.

It’s always been the case, if you go back in the history of climate policy to the 1980s and 1990s, everyone’s always understood that this won’t work—the energy transition, the move to a green energy system, unless it is rolled out to the entire world. Because no one has really been able to contemplate a world from the ’80s onwards, from the Brundtland Report on sustainable development. It has not been a plausible suggestion of a future that the world doesn’t develop. Once upon a time, you might have said billions of people are condemned to poverty. That isn’t a plausible hypothesis from the ’70s and ’80s onwards.

So there’s always been an idea that we need to roll out green technologies. But the problem, of course, is that up to the present moment, until the very recent past, those technologies have been utopian. They’ve been hypothetical. So what we’ve seen is various types of development policy, which have been financial architectures rather than actually translatable solutions.

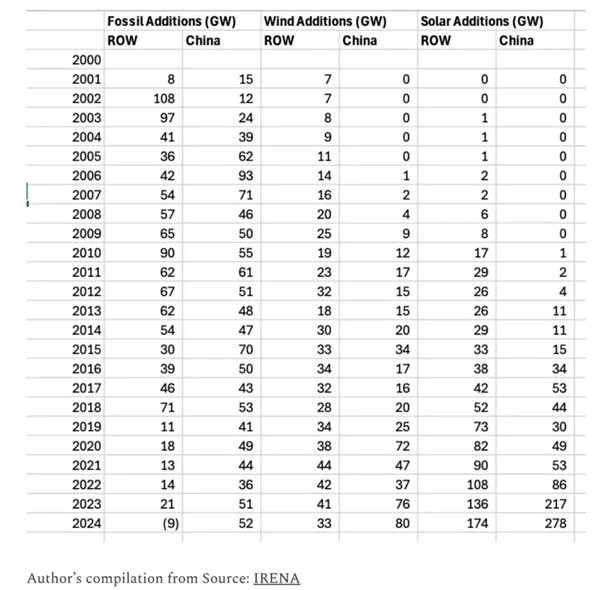

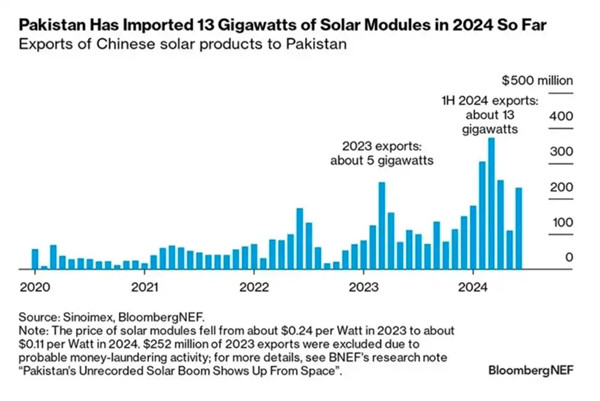

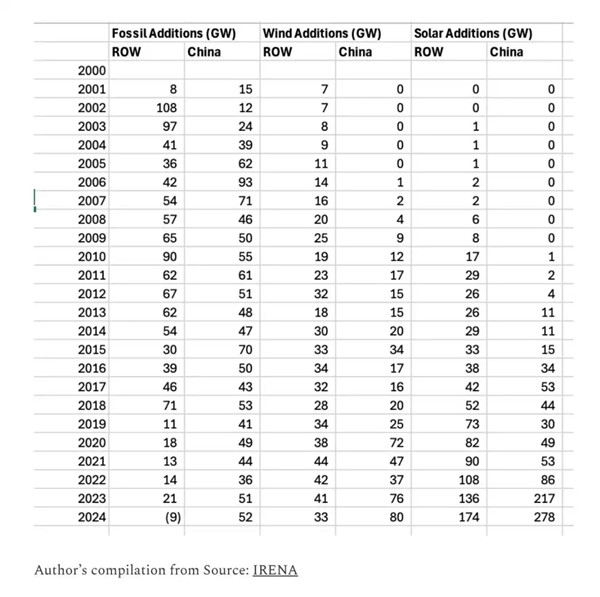

Sorry for the coarseness of this graph, but the numbers are really dramatic. They come from IRENA. China’s huge surge in renewable energy capacity changes the game, and it changes the game for everyone in those four quadrants of the global energy transition. I don’t need to tell you and belabour the point here, but the numbers really are worth thinking about.

Here are, from IRENA, the annual net additions in terms of gigawatts of fossil fuel, of wind, and of solar, and this is China compared to the rest of the world.

And what this tells you again is that what we are going through—and what China has gone through—is not in one but in two bursts. There’s a big burst in China, if you look at solar, in the 2010s, and then a second huge, gigantic surge in the last two years. So, as a historian, again, I’m insisting on specificity. This is a fast-moving story with a profile of acceleration that’s truly dramatic, and it changes the balance radically between China and the rest of the world, crucially in the dimension of solar, and also in terms of wind, where China’s dominance is, if anything, even more spectacular than it is with regard to solar.

The question mark, of course, is: what is the future of China’s ongoing investment in fossil? China, as you will know, is the only substantial global investor in coal at this point. I mean, these are really mind-blowing numbers. What this is telling you is that nowhere else in the world is investing positively in fossil at all last year. The only country adding any substantial fossil capacity in the earth is China. The only country. So when I say that China becomes the singular centre of the entire global energy drama, I’m literally not exaggerating. It’s true. It is the entire fossil game and by far the dominant wind and solar player.

And to reiterate, global politics is having a really hard time adjusting to this utterly lopsided state of affairs, which has emerged since COVID, really. This wasn’t the case before COVID. China, in fact, went through a lull—many of you will remember it—in renewable energy investment just before COVID as the subsidy regime was shifted. And then in the aftermath of COVID, there has been this sudden, spectacular surge.

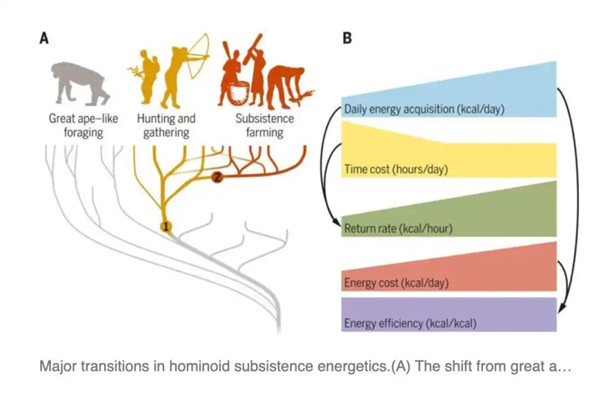

And what I want to say is that this opens up possibilities of transformation at an even larger historical scale. Like, I started by saying that the entire economic and industrial history of humanity can be summarised through that coal consumption graph. But what we are looking at now, with the massive rollout, with the spectacular rollout of solar and wind, is a transition at the anthropological level.

What we’re essentially talking about is moving a system from a hunter-gatherer mode of energy procurement—which is what fossil fuel action is—to a farming model of fuel generation. We’re going to produce power in the same way as we produce food. We cannot feed 8-plus billion people by hunting and gathering. We feed them by intensive agriculture. We are going to provide the energy systems that we need in the same way. And this is what’s being made possible by the gigantic scale of solar and wind.

The other thing that this does is that we move from a world in which energy is essentially produced in autonomous ways—in other words, people locally burn their fossil fuels to drive their blast furnace or fire their car. It truly is—you spend a few days in Beijing and you become increasingly shocked by the internal combustion engine reality of the city that I still live in. In the hutong I’m living in, there are no internal combustion engine cars. Everything is electric. It’s silent. It moves past us. The implication of that is a) immediately less pollution, but it also means that the entire system is a system.

When I fill my car up with petrol, it’s for me to go burn it wherever I like, right? That’s the freedom that the petrol offers—the fossil fuel civilisations. This is why the Americans are so profoundly committed to it. Be part of an electricity-based system, and you are inherently dependent on a network. You are profoundly and irreducibly dependent on a complex interchange. So here we are looking at a transition at the level from fossil fuel autonomy, if you like, to networks. And people in the West are increasingly contrasting the American model of fossil fuel autonomy with the Chinese model of electrostate. So it’s an inherently political organisation.

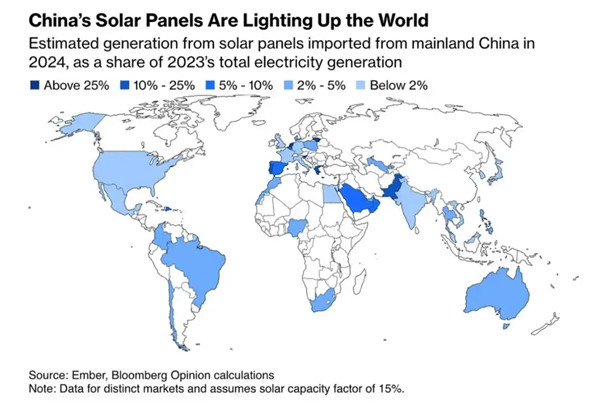

And the third thing that has suddenly become possible is that global transformation at a technological level is, in fact, truly conceivable. So the idea of electrifying Pakistan at the numbers that I’ve quoted here from 2024—this is one of the truly amazing stories. Pakistan, an emerging market economy—obviously one with very close connections to China for diplomatic reasons—a chronically broken power system basically imported a national capacity worth of solar power and batteries from China in a matter of months. This is becoming conceivable.

And it’s happening. These are data from Bloomberg. This is not Chinese government sources. These are data being compiled by Bloomberg showing the transformation of the global energy system being enabled by the cheap provision—the ultra-cheap provision—of Chinese solar. So three fundamental transformations: from hunter-gatherer to farming energy, from autonomy (individual fire burning) to electrostate, to third fundamental transformation—the possibility of a truly global rollout.

This is delivering the “second China shock.” This, combined with the tech revolution—China’s incredible advances in tech and AI—symbolised, of course, for those of us in the West who follow the American markets, by DeepSeek. This is the core of the second China shock. Unlike the first China shock analysed by American labour economists, which was a socio-political shock—in other words, it upheaved American society in parts—this is one that actually challenges European and American leadership at a strategic level.

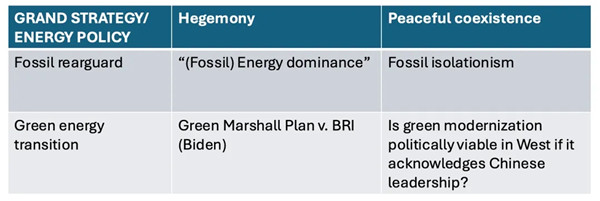

And here again, it might be useful to think in terms of the way in which this is disrupting Western politics. So this is a two-by-two in which I’ve put energy strategies down this side and international strategic options on this side here. And what this allows us to map is the narrowing window, if you like, for progressive, dynamic, green strategy in the West.

At one end, we have fossil rearguard American hegemonic strategies, which are exemplified by certain parts of the Trump administration, certain parts of the American power apparatus, which you might describe as an energy dominance strategy. This is how they themselves speak about it.

You might also, however, think about a future strategy for the U.S., which consists of a kind of fossil isolationism. It’s hard to deny, I think, increasingly, that this might be a strategy which the Americans are currently aiming at—let China do the green energy transition, we will live within our fossil world. And it’s possibly one of peaceful coexistence, except the climate will, of course, continue to be stressed. But it doesn’t imply an international position.

What we saw with the Biden administration was an attempt to reboot global hegemonic aspiration on the part of the United States, and to combine it with green energy transition. This was the talk about a Green Marshall Plan, Just Energy Transition Partnerships, all of them quite explicitly pitched against China in a progressive, modernising green vein. The challenge for green modernisation strategies, which in fact prioritise green energy transition in the West, is increasingly whether it’s possible to combine them with something you might describe as peaceful coexistence with China. That becomes the central question mark: Is this possible? Is green modernisation politically viable in the West if it acknowledges Chinese leadership?

And this was a question that we saw powerfully struggled over in the last German government with Baerbock and Habeck of the Green Party—both the champions of the green energy transition and the champions of a relatively hawkish, values-based foreign policy. And the two things sat very uncomfortably next to each other.

The challenge for the Americans is obvious, I think. They’re a deeply fossil-fuel-committed society. For the Europeans, you can read it off here. This is the same numbers as we had earlier, as percentages, and what this tells you is another story of European decline. Because this is the share of renewable investment that was attributable to Europe over the last 25 years. And you can see why the Europeans have an almost nostalgic attachment to the idea that they are the leading green power, because there was a period in the 2000s in which they were, to a truly dramatic extent.

And in fact, if you speak to German counterparts, you’ll hear them tell you that China’s green industrial development is largely owed to the benefits of the German subsidy regime of this period. The humbling reality, of course, is that now they are all fundamentally eclipsed by the dramatic rise of China. This is the narcissistic problem for the Europeans: Is it possible really to get over the fact that China has become the dominant power?

So, that’s the political strategic problem posed by the China green energy shock. What about the economics? Well, economically, China’s new energy revolution is a huge shock, because it’s not the same as the first China shock. The first China shock was, in fact, initiated by Western elites themselves. It was initiated by the generation of American policymakers in the ’90s and the 2000s that saw huge benefit from bringing China into the WTO. It was initiated by people like Hank Paulson, who was Treasury Secretary for Bush, as Goldman Sachs’ CEO, who was managing the strategic partnership with the United States.

The price was paid in the West by a limited section of the Western working class who were hit by relatively low-value Chinese imports in sectors like textiles and basic manufacturing. And it was secured by the fact that Western populations as consumers were huge beneficiaries of cheap Chinese imports. So this was a stable social bargain, as long as it lasted.

The China shock 2.0 is much harder, potentially, for the West to digest, because it’s China-driven, not Western-elite managed. If you want to point to the source of agency, it will be Made in China 2025—just for sake of argument. That’s crude, but nevertheless, it gives you an idea of where the agency lies, and it challenges core interest groups in the West, deep down into the power structure of the West.

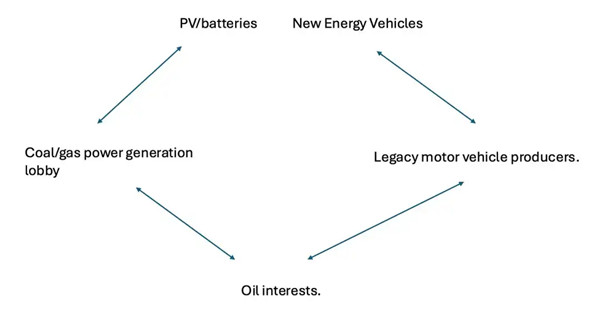

If you were to map the force field that is at stake here, it’s obvious, but I think, to me, it’s again and again worth putting this on the board. There are two groups of interest that are powerfully shocked in the West by the Chinese green energy revolution.

The PV (photovoltaics)/batteries hit the energy-generating sector. That’s the electricity-generating sector, and that’s not oil—oil isn’t used for making electricity. That’s coal and gas in Europe and in the United States. And that’s a very, very powerful and entrenched group.

The new energy vehicles hit the motor vehicle sector. The motor vehicle sector matters. You might think America, Henry Ford, Detroit—in the United States, the motor vehicle sector is a subordinate player, because Ford, GM, Stellantis are so lost now. But in Europe, they’re the dominant interest group. And in Japan and South Korea as well, they’re profoundly significant.

So, you have a two-pronged challenge. And behind all of them, to an extent that’s actually really quite interesting how buried it is, sits oil. Oil sits at the intersection here because insofar as the new energy vehicles replace the legacy motor vehicles producers, of course, the oil interests lose out. And oil interests in the U.S. now allow coal and gas to do much of the heavy work in campaigning against green energy policy.

So, how does this play out? How do we go forward from here? How do we think as social scientists, as historians, about a shock to society like this? Let me conclude by making a few observations about this.

How do we think about this? Well, these are problems—and I’ve hung them up, as the Germans would say, this high—at the level of world history and species being, because these are problems, I think, which challenge the very foundations of modern social theory. And modern social theory in its classical form does offer us some ways of thinking about these problems.

Karl Marx is undoubtedly a thinker of an energy transition like this. And I’m going to leave that tradition for my colleagues in China to think through. In the West, unsurprisingly perhaps, that’s not the main mode of policy thinking about this issue. The main mode, if you want to understand the way in which critical social scientists in the West think about this issue, it’s Karl Polanyi.

Why Karl Polanyi? Not because he’s as brilliant as Karl Marx—he’s a journalist, he’s a second-order thinker. But what he does is to problematise and theorise, and there may be specialists. The last time I was in Beijing, why did I say that? Last time I was in Beijing, I ran into somebody who was a huge specialist on Karl Polanyi, and they schooled me on Karl Polanyi. So, no disrespect to Karl Polanyi—he’s a fantastically interesting thinker. He’s a fantastically interesting thinker because he thinks the relationship between capitalism and democracy. And whether we like it or not, on either side, the problem of the green energy transition in the West is thought through the prism of the relationship between capitalism and democracy. It is through its apparatuses that this problem is processed.

What Karl Polanyi diagnosed is not a neat dialectic—not a dialectic that resolves in a dramatic and final way—but a “back and forth” between interests in society shocked, and then attempting to reassert leadership and control over society—what he called the “double movement” in the process of economic development.

Now, he describes this for one phase you may know: from the 19th century unfettered economy, the making of the economy, into this weird autonomous thing. Karl Marx, of course, writes about this in theories of alienation, for instance, and the mystery of the commodity. For Polanyi—he’s an anthropologist-historian—he looks at the 19th-century world almost like an anthropologist from Mars and says, these people are crazy. Why have they allowed the economy to run free like this? How does society respond? It responds with social protectionism. It responds with tariffs on trade. It responds through the limitation of agricultural commodities to protect the land. It responds through the creation of a managed money system like Bretton Woods to replace the gold standard. We enter the period of Keynesian management.

And if you ask how Western theorists think about the way in which we expect the shock—this second China shock—to be managed, it’s through mechanisms like that. Please don’t be surprised by Western protectionism. It’s the most obvious reaction in the world. The last time I was in Beijing, I encountered all sorts of indignant responses: Why are the Europeans resisting? Why don’t they take our cheap, wonderful BYDs? Because there’s 2.7 million people that work in auto manufacturing in Europe. And because it’s a democracy, they’re voters. And so, if those voters vote the wrong way, we have huge governance problems.

And I can show you the AfD populist in a German car factory who’s mobilising a right-wing nationalist, racist politics, which you’ll like even less than the politics you’ll get from the Red-Green coalition, the Ampel coalition, or the CDU. So on the part of Beijing, a realism about how these mechanisms work is really fundamental.

What interests me, of course, being here is how this plays out in China. Because I’ve described this as an international logic. But if you go back to the beginning of the talk and you think about what China’s got to do, you, me, and everyone else in this planet is hugely invested in how this story plays out here. Because we would, of course, be kidding ourselves to imagine that it doesn’t play out here. I don’t think anyone could be naive enough to imagine that it doesn’t.

China has been through far too many shocks, and we understand the political economy of those well enough to know that if China is going to leave the coal complex behind, there will be massive politics to be played out—class politics, urban politics, regional politics, between provinces which are coal-heavy and provinces which aren’t. Those in the West that have a new energy future, those in the old Maoist Rust Belt that maybe don’t have a new energy future. How is that going to play out?

I was reading Caixin the other day—had a brilliant report on Great Wall Motors. Not a firm that most of us in the West spend much time thinking about, because it’s not BYD. Everyone in the West is obsessed with BYD. Why don’t we think about Great Wall Motors? Because all Great Wall Motors does is internal combustion engines. It was described as a “fossil” in the headline of the Caixin report. It was really, really illuminating.

Where are they going? The same bad, low-end markets the American manufacturers are going to. It is pursuing fossil isolationism within China in the current moment. Where is it going? Literally, Russia. Great Wall Motors’ major market right now is Russia. The other markets it’s looking at are Brazil. It’s looking at the middle-income market.

So, if China is going to accomplish that incredible hairpin bend, I want to know, as an outsider, how these political economy moments play out here, because there isn’t a more important drama in this moment of history. What happens in the West is significant, but it is fractional compared to the scale of the stakes right here at home.

Thank you very much for your attention.

Thank you, Adam. That’s just classical Adam Tooze, and I think we all enjoyed it very much. It’s just fascinating.

The next stage of this event is to have Henry Huiyao Wang, the Founder and President of the Centre for China and Globalisation, join Adam Tooze in the conversation. It is part of CCG’s Global Dialogue series. The series actually started, I think, amidst the COVID pandemic, when travel between China and the rest of the world was basically shut down. So, Henry started this initiative to talk with foreign dignitaries and public intellectuals.

Among the conversationists in this dialogue, we have Hank Paulson—who you just named—and Niall Ferguson, Stephen Roach, Pascal Lamy, Graham Allison, Angus Deaton, Adam Posen, and many others. So, we are very glad that after the COVID pandemic, CCG is able to continue this dialogue, to promote the knowledge from China and also from the outside. We will post the video recording both on Chinese social media as well as on YouTube. We will also transcribe this dialogue, as well as the lecture and the Q&A at this scene, so that the wisdom from Henry and from Adam Tooze can be heard by many more people, fulfilling the mission of the Centre for China and Globalisation.

For those of you who do not know Henry very well, he is the Founder and the President of perhaps the No.1 non-governmental think tank in China. He was appointed as a Counsellor for the State Council, China’s government cabinet, in 2015 by China’s then Premier. Before that, his career spanned the Chinese government, the Western private sector, and then China’s public sector. He was a visiting fellow at, I think, Harvard Kennedy School. He was a senior fellow at Brookings. He founded CCG together with Mabel Miao in 2008. And under his leadership, CCG has grown to be one of the leading non-governmental platforms for dialogues like this, as well as for Track II diplomacy between China and the West.

He has also played pivotal roles across the world. He is, for example, the only Chinese national on the Steering Committee of the Paris Peace Forum. Often, CCG, under the leadership of Henry, is perhaps the only Chinese organisation at events like the Munich Security Conference and the Aspen Security Forum.

So, let’s also give a warm round of applause to Henry to join Adam Tooze and have this wonderful conversation.

I remember when I was talking to Larry Summers two or three years ago, he was saying that lifting 800 million out of poverty was something comparable to the British Industrial Revolution. But now you’re having this green transition—Green Revolution—which is probably even more impactful, more sustainable. So I’m very happy that you have given this very comprehensive overview of your research and your findings.

I have some questions. You are a historian—a very famous historian. In your recent research, you described China’s renewable energy surge as unprecedented in human history. That’s something, which is true. I think that since COVID, we noticed that acceleration. This newly installed capacity has been really staggering, and it’s a huge paradigm shift. The capacity installed is exceeding the rest of the world combined.

So, from your perspective as an economic historian who has done a lot of studies, how do you evaluate and situate China’s green transition within the broader arc of global economic history? What historical precedents, if any, can help us understand? I think you’ve made a lot of comments there already, but I’d like to know: what is this going to be the future of global governance and green governance? Can this new paradigm shift be modelled in a way that works out both for China and for the rest of the world?

I see that you mentioned very correctly that in Germany, the auto workers don’t like BYD because they have a lot of local labour employment issues, tax issues, and the local voting process. So, how, in the long run, can we solve this? And what can be the solution to that?

I mean, this is the fundamental question. I think maybe one way of thinking about this, to kind of double down on something I said, is that in terms of climate politics, the first phase—shall we say, the first half-century—was almost—I mean, it’s astonishing we have climate politics. They start there. It’s mad. It’s extraordinary, right? It’s this far-flung hypothesis that if you measure really, really hard, you can see a gradual increase in CO₂, which we only really began to do. Do you know what? They began to do it because they were doing above-ground atmospheric hydrogen bomb testing, and they decided it would be a good idea to measure the composition of the atmosphere before they exploded many more bombs. The ’60s were extraordinary in terms of anthropocenic ambition—no one had any problem with exploding hundreds of huge hydrogen bombs in the high atmosphere.

So, in that spirit, we decided to measure and then hooked up with a bunch of speculative science, which said there could be global warming. By the ’80s, we kind of began to believe that was true. But we also, in the ’80s, realised that if you took this at all seriously, it meant the end of the world as we know it from the industrial point of view. There is no version of the world that began with the Industrial Revolution that’s compatible with this hypothesis.

So, unsurprisingly, it kind of banged around international conferences for decades because everyone could see the problem. It wasn’t very real in the short run, but the science seemed incredibly serious, but the possibility of changing the world was just far too daunting. So, little happened.

This is all building up to the colon, and then China actually decided to push towards manufacturing wind and solar at actual world-changing scale. And it’s only really in the last 10 years that we’ve gotten to that point.

So, when you ask, how do we adjust to this? The short answer is—it’s the old cliché—it’s too soon to tell, comrade. It’s far too soon to tell. This is going to take some time to figure out before we wrap our heads around this.

Like in your report, you say the IEA says $4.5 trillion [on renewable energy annually]. We’re nowhere near that yet. One thing we know is we’re going to need unbelievable numbers of photovoltaic panels. And what we already know is that Europe and the United States are going, “Oh my God, we can’t cope. Like, there’s far too many.” And yet, the answer from all the scientists is you need even more.

So it turns out that first you start thinking about it and go, “This is a huge crisis. Oh, there’s nothing we can do.” And then you get to the point in the last 10 years where the Chinese go, “Well, there is something we could do. Here are the photovoltaics.” And then in the West, the response is, “Oh my God, we can’t actually do that, not with yours. I mean, we’re going to make them.”

So I think we’re still, in terms of this relationship, shall we say—or like stages of grief—we’re in kind of an early stage of coming to terms with this process. I’m not impressed by ordering projects, like the plan for some big solution. But what I do think is possible now is real change. What we can do is actually secure sustainable electricity in Pakistan. Pakistan is a non-trivial part of the global jigsaw puzzle. To be able to do that is huge.

Could China, for instance, agree to bolt its baby CO₂ pricing system onto the European, much more sophisticated system, and get real about CO₂ pricing in China? Yes, it could. That would make a huge difference. Would it be a global carbon price? No. But it would be two large pieces of the world economy and a very sophisticated mechanism. That would be a step in the right direction.

Can you do this with the United States in its current form? No. Don’t even waste your time. It’s not worth bothering. They’re living out their own drama. But could you maybe do it with Brazil and Europe and China? Absolutely. And so it will be those kinds of steps. We should recognise how early in this process we are.

Like the CCP, the Chinese Communist Party, thinks, as we know, in multiple generations, ten generations, that kind of scale. We don’t have that amount of time. But we definitely are in a process of generational, epic historical adjustment. So, that’s why my answer is modest, not because I don’t understand the force of your question, because I just think it’s just too soon to tell.

Absolutely. I think we are seeing now, of course, some unease on the trade war, tariff war, and also China–West relations in general, there are sometimes tense relations. But I think that this new Green Revolution could probably be a solution to soften these tensions in the long run.

For example, you imagined exactly right—you talked about Pakistan, you talked about Brazil, and many other things. I’ve also been thinking, in your presentation, you mentioned Africa. Something comes to my mind, like solar power in Africa. Africa has abundant sunshine. Let’s do a huge solar farm there.

And then, if we can solve this transmission problem, let’s get that power to Europe. China could invest in the African solar farms, and the power could be harvested by the European Union. They are now trying to diversify away from Russian energy reliance, which is great. So there’s no risk, actually, for Europeans to have the power from Africa, but China already invests heavily. And that could be a win-win. Africa gets some revenues as well.

But this—this is a vision which, I know, if you speak to people in Namibia, if you speak to people in Africa—I host a regular panel, it would be very great to welcome a Chinese colleague to it. We host a monthly panel, hosted by the German Böll Foundation, on the problems of green energy transition. It would be fantastic to get a Chinese perspective. If there are colleagues from this group who’d like to join, they’d be so welcome.

And we recently heard from a representative from Namibia, where they’re thinking about doing precisely that kind of project. Because, obviously, it’s a desert state. They want to do hydrogen. They want to do green hydrogen. They want to do some of the supply chain, so they won’t just be a raw material export. And Chinese photovoltaic is key to that.

But don’t underestimate—in that vision you were carrying forward, one of the key moments was, okay, then we’re going to do transmission on a large scale from Africa to Europe, right? I didn’t even say this, but the space where China has completely ruptured the envelope. You could say, with photovoltaic and wind, the Europeans and the Americans pioneered the technology—solar came out of California, wind came out of Europe. China scaled it up and did it bigger and cheaper. But where China has completely broken the envelope, and is actually mapping a world in truly utopian terms, is ultra-high voltage transmission. And no one else is even close to the scale of the buildout that China is pioneering.

But that, let’s be honest with each other, is the global electrostate. That will be the China State Grid, using its completely unprecedented expertise to do something we definitely need. But it’s the China State Grid, and it has the China State Grid label on it—proudly, and rightly. But that’s what it is.

So at that point, the politics of this intrude. And we need to talk détente. We need to talk mutual coexistence. We need to talk protocols. We have to get real about the politics and not pretend that this is just great technology, because power is entailed, and dependency is entailed. And as quickly as China’s technology develops, the fear of dependence on China’s expertise is real. And again, Chinese policy won’t succeed unless that is factored in, right?

Well, I think probably this is an evolving process. It won’t happen in the short term, but it’s going to take a long time, probably. But again, you’re absolutely right. You know, Chairman Mao used to say that you start from the rural, and then that’s urban. So, probably it’s good to start with developing countries—if they are more accepting of green solar, EV cars. And then, when that has been benefiting Central Asia, Latin America, Africa, and Gulf countries, that spillover may someday come to the others.

I had Pascal Lamy coming to my office just a while ago. We were talking about German Volkswagens and BMWs all here, but let’s have those JVs in China reinvest back into Europe someday and have a JV approach. It’s probably more acceptable by that time, if we can really work out something.

We’ve seen it in the last two years. I’ve been in meetings in Berlin—I was at one of the early meetings where somebody said, “Oh, I’ve got an idea. We’ll do the opposite of what the Chinese did to us in the 2000s. We’ll invite them, and we’ll steal from them, rather than the other way around.” And it was like this ripple of recognition in the room of going, “Okay, well, that’s a great idea. Could the government actually do that? Could we set up a JV and invite a Chinese firm, and then we’ll appropriate their technology?” We literally watched it happening.

But go back for a second and pause, because this is, I think, something that China’s experienced after all—one of the things, so many things it teaches us is that when large-scale development happens, it’s obviously a huge human benefit, but it also utterly changes the power balance. Because it constitutes the most powerful nation-state the world has ever seen. China is the most powerful single nation-state the world has ever seen.

Now, imagine—there won’t be another like it. I don’t think it’s plausible to imagine India emerging in the same way. But then imagine, for a sake of argument, that that project you’ve just outlined works in Africa. We would then be facing a world of multipolarity, the likes of which we have never seen before.

Imagine, 20 years from now, a successfully developed Nigeria, a successfully developed Ethiopia. Even if the Nigerians got to Turkish levels of GDP, it would completely transform the politics of West Africa in a staggering way. Because that’s going to be a 350-million-people state. In the sustainable development idyll or under the auspices of major political power, that’s not just humanitarian benefit—fewer babies die, fewer mothers die in childbirth, Nigeria steps forward. In a world without that hegemonic envelope, who knows what Nigeria does next with the power that will be conferred on Nigeria by that development? We genuinely don’t know.

And so, to my mind, unless we think that project to its logical conclusion, we’re not beginning to encompass the world that we’re getting to. Part of it is relativities, and that’s quite a high standard—catching up is really hard to do. But in terms of becoming a significant global player, it’s thresholds that matter most. It’s about whether you get to drone competence right now. And to get to drone competence, you don’t need to converge with the United States. You need to cross a threshold of like $5,000 PPP, something like that, and all of a sudden, you can begin to do really regionally significant stuff.

This is why we need to go back to Sunnylands, we need to go back to a new model of great power relations, we need to actually be thinking through some kind of comprehensive model of global geopolitics.

I agree. Basically, now you see from this time that, even from the trade war we are having now with the U.S., you can see it’s totally different from the first term. Because China has more experience now. Trump is more flexible, and they’ve been reaching Geneva, London agreements, and things are starting to smooth out somewhere. And we are now talking about Trump may come to China sometime.

But what I think is, with the multipolar world coming, where is the common denominator for everybody to focus on? The climate threat, climate change, is still probably going to be the bigger politics. And in that sense, China and the EU have a common understanding. Trump may have a different view, but he’s only there for three and a half years, and then we may have another one who has a better understanding coming up. So, if they have a common focus on this green transition, and China is leading on that, there could be a way of peaceful coexistence somehow.

Of course, COP30 is one of them, but we could have more mechanisms than that. Europe can conduct studies on that. For example, we talk about BRI, could we have a green BRI? A digital BRI in addition to the green BRI? Green BRI means 150 countries will sign MOUs with China. Let’s green them first, and then the world benefits from that. And then gradually, we’ll see cheaper, more productive models.

Recently, I was in Brussels last week, and I heard a story that Geely has teamed up with Volvo to manufacture EV cars in Belgium. And believe it or not, they were telling me that the cost of making an EV car in Belgium now is comparable to China or even cheaper. So that’s without any subsidy from China. It’s made in Belgium. Maybe it’s because of automation or technology. That’s very interesting.

So if we can have this win-win JV approach back into Europe or sometimes in the U.S., as I recently wrote in an op-ed, China invests everywhere, provides local opportunities and benefits. That could be a solution to the trade war or something in the long run.

So what do you think about this—starting with developing countries, the Global South, and then the spillover to middle powers, and of course, to Western countries? And then, if we use this green as a more moderate, softer approach, this is really a common threat we have to face. So the multipolar world needs something to glue on to hang on.

So, I mean, I would take up two elements of that. One is that, speaking to, say, Indian colleagues who are part of this dialogue that we do through Böll—it’s one of the most valuable things that I gained from talking to them—is they say: forget climate. For the poor developing countries—and India, in large part, as anyone who’s been there knows, is still a very poor developing country, with hundreds of millions of people—it’s all about the green energy transition. That is a story you can sell. So that is a common denominator.

What people want is energy, and they want it now. Climate is a problem over decades. It will affect certain parts. It’s affecting us now, but it’s not affecting us as acutely as not having power. Not having power is the absolute priority. And having green and clean power that doesn’t pollute, doesn’t give your kids asthma, isn’t coal, is a true universal. And that is something, I think, to structurally organise around.

So, at that level, yes. The problem is the manufacturing side of the story. And I really do think that this is another one of these adjustments that Chinese policy thinking is forced to go through because of the historic nature of the change. I mean, we have moved over the period of the last 20 years from “China Shock One” to “China Shock Two,” from a world in which China could compete on low cost with relatively low productivity and low sophistication in many key areas of manufacturing, and kicked off development that way. We’re now in a world where China essentially has dominance in the economic sense. In other words, it’s better in every way in a huge swath of mid to high-tech manufacturing. Forget the low end, which it already totally dominates. Its share of global manufacturing has rocketed to a third. This is an utter, utter transformation.

And I do think that this poses really deep questions of adjustment for China’s positioning in the world, because that dominance—and it is dominance—of so many areas of production, very high quality, very high flexibility, and integration across the entire supply chain, and reasonable cost, means that it’s difficult for other people to imagine their economic future.

Now, the economist has an answer to this, and it’s called comparative advantage, which says that even if China is better at absolutely everything, that doesn’t mean that it should entirely dominate trade because there are still spaces for other people to produce into. Bangladesh in garments, for instance. Doesn’t make sense for Chinese labour necessarily to specialise in that.

And this is where I would then connect with—I’m going to channel Michael Pettis here or Brad Setser and bring the macroeconomics back, which is that China can make its dominance of the higher end of manufacturing less terrifying for the rest of the world if it becomes a bigger buyer of other people’s manufactured goods. Right now, China is, if you’re Brazil, a wonderful customer for Brazilian raw materials. But it is not a customer of Brazilian-manufactured goods. That, I think, is a major issue.

And if you think about, say, the British model of hegemony before 1914, it relied incredibly heavily on import power. China doesn’t deploy its import power anywhere near as far as it might.

But maybe I’m just thinking, you know, that could be an interesting way for China, probably—because when China is accused many times of subsidising and doing a lot of things—I remember one year I was at the Munich Security Conference, and a colleague from the German Council on Foreign Relations was saying, “Look, if China can give the world cheap solar panels and high-quality products, let it be. Let China subsidise the world.”

As you said, if China is not buying enough, maybe China can really provide good products for the rest of the world, and in a way, to Africa, to those developing countries. So maybe that is the way to address some of those imbalances.

I mean, the problem with that logic is, if I may, I’m just going to think this through. Like, who paid for the very cheap photovoltaic panels in China? The Chinese tax base. All of you in this room paid for them fractionally by having a lower standard of living and not enjoying the full benefits of the economic prosperity.

And so the full rebalancing story is, in fact, to redress that imbalance, to refocus Chinese economic growth around consumption and human services, to centre China on the new problems of economic growth, which are beyond new energy and micro tech. They’re about the human. They’re about human services. They’re about welfare. They’re about the demographic crisis. They’re about childcare. They’re about the possibilities of social reproduction in China as it becomes affluent.

China has demonstrated to the world that it can do manufacturing. It can do heavy infrastructure. The question is: Can it create a policy framework for a more balanced socio-economic system?

Yeah, I would think maybe in the long run, China has to do more technology transfer in terms of green technology because it does have to find a way through competition. For example, there were several hundred EV car producers in China. Through fierce competition, there are now a few dozen left.

But I think that we are now finishing the 14th Five-Year Plan, and we’re getting the new Five-Year Plan starting from next year. When President Xi said at the UN a few years ago that China was going to realise carbon peak, it was not “by” 2030, it was “before” 2030. Carbon neutral is before 2060. So “before” could be a few years ahead. For example, 10 or 15 years ago, Beijing was heavily polluted, but the mayor told me that the reason for that was 60% of the pollution came from automobiles. Now you go to Beijing, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, or Shanghai, over half of the automobiles are EVs.

So I think that kind of benefit could be spread around the world. When one locomotive was invented, that revolutionised the world. When Edison invented electricity, it revolutionised the world. But what about this EV? China’s green power revolutionisation could benefit the world.

I agree with you that we need to find an acceptable, more mutually beneficial way of doing that. And I think we’re still in that process. But I’m very pleased that you spearhead this kind of research on green transition. That, in this new industrial age, is really relevant.

So maybe now I’ll turn to our audience for some questions and comments.

Cui, Zhiyuan, Professor, School of Public Policy and Management, Tsinghua University

Yeah, thank you to both of you. Such a wonderful presentation, very good discussion. Adam, I’m not sure how VPN works in your hotel today. Today’s Financial Times has a report that, this November, Brazil will hold COP30 in Brazil, but one of the key challenges President Lula has to deal with is that some scientists now publish and emphasise that the 1.5-degree target has already been surpassed now.

So I think this cuts both ways. Because on one hand, we’re seeing this urgency of the climate crisis, but on the other hand, this challenge is maybe the right-wing climate change deniers will use this to say, “You actually, from the very beginning, exaggerated the crisis. Because now, we’ve already surpassed 1.5, and we are still, it seems, basically okay.”

So this is in connection with the recent debate about whether or not total reliance on wind and solar in Spain and Portugal caused the recent crisis, and there’s debate whether this is really the cause. But you can see, my question is about: What do you think about these new problems in climate politics?

Those are indeed very pressing questions. I like the way that you frame them. It is undoubtedly true that 1.5 degrees was always a political [threshold]. Global climate politics is a weird, theatrical creature. It’s kept alive almost by suspension of disbelief. Like I was saying earlier on, the problem was identified decades before we had any remotely feasible solutions, and we still don’t really have a viable roadmap at the global level.

Nevertheless, at Paris in 2015, it seemed crucial to anchor at 1.5. And this has to do with the logic of global climate politics, which is that it’s UN General Assembly–driven. And in the UN General Assembly, the small island states, which are a tiny fraction of humanity, but are really, I think, about a quarter of all members of the United Nations General Assembly, have a very large voice.

And in that voice—it depends on how you look at it—either a totally unreasonable imbalance: Why should a monolith like China or India care about 100,000 people living on a Polynesian island? Like, that’s one block of Beijing. Why should China care? And on the other hand, out of that voice speaks the principle of sovereignty, the principle of human diversity, autonomy, which the United Nations General Assembly is designed to represent and to respect. And it’s a really fundamental tension that sits within climate policy. The 1.5 degrees was agreed to enable some kind of agreement on a deal because if we had agreed to a more “reasonable” target of 2 or 2.5, from the point of view of those states, we’re basically signing a death warrant for them.

And we are still negotiating. I think we’re going to go through a prolonged process. This goes back to this point about it’s too early to tell. Some of us are so old that we are not going to see very much of this process, but over the next quarter century to 75 years, we are going to see a creeping, progressive adjustment of the entire planet to a warming, which, I think, reasonably, we now have to expect is going to be 2.5 degrees at least. We’ll be lucky if we stabilise short of 3. And we don’t know what the consequences of that are, but it’s going to be disruptive. And this is a moment in that process.

So the first quadrant is high energy, low growth.

Sorry, it’s just that quadrant in general. Is it possible for any of those groups to move between different quadrants? Or are we saying for kind of path dependency reasons, everyone’s kind of locked into those groups? Or, as Henry mentions, could outward investment solve some of this problem, and could China share some of this growth with the rest of the world, be that the EU or actually helping with the sub-Saharan African problem of low growth?

Oh no, absolutely. The aim of that grid is not to fix places. It is to widen our perspective on the current snapshot of what the energy transition problem looks like. So the aim of the game is to get us out of our G8 thinking, and to understand that there are four other problems out there. And it comes actually out of the lived experience of engaging in these dialogues through Heinrich Böll with colleagues all over the world.

And people in India just laugh at you when you talk about energy transition. They’re not transitioning anything. They don’t want to shut a single coal-fired power station because their per capita energy consumption is a fraction of ours. And so forget it—like, they will reduce their coal-fired power stations when they have enough electricity for people to have more than a light bulb.

And people in Mali shouldn’t be talking about this at all. And there’s something absurd about the EU sanctioning or refusing to provide development assistance for African countries that want to have gas power plants, right? Because they’re not going to go down the terrible path we’re going down, for which we desperately need gas. It’s a grotesque misunderstanding of the relative balance.

And so, absolutely, of course, countries can transition. I mean, China—the story I’m telling is that China popped from here to there, right? That’s literally happened in our lifetimes. It’s still quite difficult to convince people that China’s per capita energy consumption now is larger than that of almost everyone in the EU. China is up there with Poland and Germany because it’s coal. It’s the coal that does the CO₂ damage.

So yes, countries flip around, and the project should presumably be to have everyone in the high energy per-capita consumption, low emissions box. But we’re going to get there—and this is the other point I guess I’m making—we’re going to get there on different trajectories.

The Indian case is, you know, down here. They’re going to bump. They get it like this. The African case—there’s really no emissions growth at all. And China has to perform this, has to perform this. So this two-by-two is really just an expansion of that graph into two extra dimensions.

And so, no, it’s not fixed. The aim of policy should indeed be to move people around. And that is what a commitment to net-zero convergence means.

I was curious about your sort of petrolstate–electrostate split, and I wonder how to think about that in the context of developing economies. I think particularly of your Pakistan example. It seems like there are ways in which it’s kind of straddling the two, not because in how it’s engaging with the solar transition, because it’s almost importing entirely, not as part of a centralised system, but to replace the centralised system that doesn’t work at all.

And I’ve just come from Vietnam, doing field work there on their solar and wind deployment strategies, and there’s a similar story of the distributed framework is much more effective currently than the centralised procurement framework, because of challenges for the grid in keeping up.

So it seems like it sort of sets up an intermediate state. I guess my question for you is: Is that kind of intermediate state of hunter-gatherer using distributed power one that is a stable one for kind of long-term development, or is that one that only exists at a stage, like it cannot fundamentally support the high-growth manufacturing path that’s required for long-term development?

I think this is a really fascinating question. It expands the argument in a very good way. I mean, you know, when you say, how does Pakistan fit into this model of either fossil-state or an electrostate? One’s tempted, flippantly, perhaps cynically, to say, what Pakistani state? The fundamental problem in Pakistan is state formation. And that brings us to a much more fundamental point beyond the flippancy, which is that it points to the fact that energy systems are profoundly politically embedded projects, right? I mean, Lenin was not—remember Lenin? What did Lenin say? “Communism is Soviets plus electrification.”

The Chinese state grid is not just an electric provision system. It’s building the Chinese state. Because, as we all know, China in the 1980s was a giant colossus. There is the Communist Party, but the integration of the regions of China, given the lack of infrastructure, is really tenuous. One of the great stories of China over the last 40 years is the creation of a national market. It’s a little bit like the United States in the 19th century, with railways, with telegraph. In China, since the 1980s, through migration, through urbanisation, through the state grid, you all of a sudden have a system where the Western power producers are linked to the coastal regions. You’ve created a state structure.

And so just to go back to your question. To my mind—and in the U.S. right now—the problem of policymaking is also about the fundamental decomposition of the U.S. state apparatus as a state apparatus. That’s the radical level that we’re reaching at this point. How far do tiny sectional interests dictate policy? Jesse Jenkins is your colleague at Princeton. If you’ve been following him on Twitter, you know the heartbreak. A large part of the American technocratic establishment is really in an almost suicidal mood this week because Congress is dismantling a state-building project. It was about building the apparatus so that America could rethink how political power operated in a green way.

And so, this is—I don’t think there’s a simple answer here. But the point I’m making is the same answer I gave to your point about hooking Africa up to Europe, is that these projects of powering up with different types of power all imply political projects. And at their grandest, when you’re dealing with huge distribution networks, you are literally mapping the boundaries of territorial states or regional governments.

And in a place like Pakistan, that’s going to be hugely fragmented because the state apparatus operates so poorly. And there could indeed be counterproductive eddies. And I believe this is the fear in Pakistan, where the private provision breaks the economics of the public grid, which is already broken, and the system spirals downwards into essentially full privatisation, which is hugely unequal because the Pakistani middle class can afford this, and the Pakistani population can’t.

Same logics in South Africa, right? You inherit from apartheid a hugely centralised coal-based system. Then the ANC promises electrification to the townships, and then the system breaks because the coal-fired plants are being increasingly dominated by various types of gang warfare and lack of investment. And then you say, okay, we could open this up to Chinese photovoltaics. And there’s a huge resistance from within the ANC apparatus because the coal miners’ union, the electric power apparatus, wants to resist an essentially privatised solution, which would give advantage to the oligarchs and the white upper-middle class—again, right?

This is why I also ended with that final challenging slide about China. Because we will really know how this Chinese story enters its second chapter when we move from radical growth, markets for everyone, green and coal side by side, to decarbonisation sooner than 2060. Because that is going to require incredibly tough decisions like this within China. And it’s going to be the destiny of the great coal-producing states. What is their future if China is going to migrate as quickly as it needs to away from [coal production]? What is the future of Inner Mongolia or Shanxi province when they’re no longer the hub of massive coal production? Where do those people go?

China has done this before. Late 1990s, heavy industrial shakeout. And we know what tensions that were accompanied by. We know what legacy it’s left in Chinese popular memory of that breaking of the iron rice bowl. That’s what’s on the horizon here. And it’s a huge political challenge for China as well. And it’s about state formation. What kind of state are you? How do you manage this? How do you manage the trade-offs? Can you do a just transition? Can the Party, in the Chinese case, mediate this somehow so as to hold this together? How do the ministries square off against each other? So as an outsider, I try to talk to as many NGO people as I can—it’s very difficult to understand how those forces will play out in Beijing and between Beijing and the major provincial power centres.

Maybe I’ll just add a brief thought on Pakistan and similar countries. I think China’s success in infrastructure and the green energy transition in general rests on a unique trilateral model of roughly 60% private sector, 20% state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and 20% multinationals. That has made China so different. And I think countries like Pakistan or South Africa could benefit from that. That kind of hybrid JV model combining SOEs may be a solution to these countries, rather than just the SOEs.

China has built 70% of the global high-speed rail network, and 4.5 million 5G stations, compared to 150,000 in the United States and 400,000 in Europe. Eventually, people will find that there is some benefit from China’s development methodology.

I also see a lot of emphasis globally on state governance. SOEs have been reinstated in many countries. Particularly for big projects, you probably need a state-enabled approach rather than the private, profit-driven approach. Someday, this may be applied to the economy on the green transition.

I think we are running out of time, but we appreciate, Adam, your coming all the way here to start such a meaningful dialogue. This will be widely spread, and we look forward to continuing the conversation with you. Once again, on behalf of CCG, thank you so much. And we appreciate all the scholars, professors, think tankers, and embassy officials who have gathered here today.

Also, I’d like to give you a book. This is the book about the dialogues we had with many others, and this is the recent book we had for Graham Allison.

Note: The above text is the output of transcribing from an audio recording. It is posted as a reference for the discussion.