Wang Huiyao in dialogue with Barry Buzan

July 05 , 2024

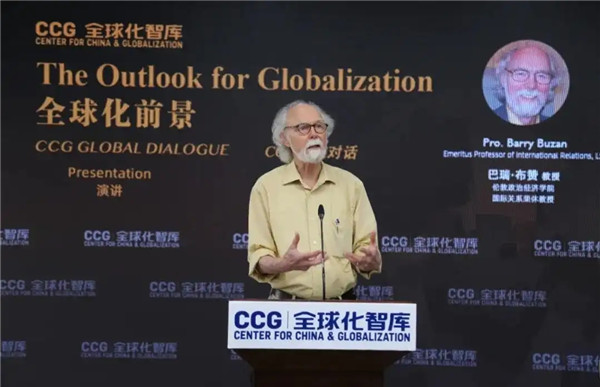

On the afternoon of July 5th, the Center for China and Globalization (CCG) hosted Barry Buzan, Emeritus Professor of International Relations at the London School of Economics, for a presentation and dialogue with CCG President Henry Huiyao Wang. Following this, Buzan participated in a live Q&A session with:

▶ Debin Liu, Professor of History and International Studies, Associate Vice President of International Affairs, and Dean of the School of International and Public Affairs at Jilin University

▶Denis Simon, Chairman of the Alliance of Global Talent Organizations, Advisor to the Global Young Leaders Dialogue (GYLD), and former Executive Vice Chancellor of Duke Kunshan University

▶ Chinese journalists from including CCTV

Presentation: “The Outlook for Globalization”

Barry Buzan:

Thank you for that kind introduction and thank you for inviting me here to CCG. I’m very pleased to be able to talk here today and to join this new network of people. I’m going to try to give a broad overview, a big-picture view of globalization. I’m drawing this in part from a new book that Robert Falkner and I have just finished. It’s now in press and will be out in the autumn, “The Market in Global International Society.” So, some of the threads I’m going to speak to will come from that work.

I want to start by giving a general overview of globalization, then look at how we got to where we are now, then take a close-up look at exactly where we are now and what kind of forces are in play, and then draw some conclusions about where globalization might be headed.

The general overview of globalization is quite straightforward. In my mind, we are in the middle of a shift from an economic understanding of globalization to an environmental understanding of it. In other words, the significance of globalization is changing from economic to environmental.

Up until quite recently, globalization has been about the global market, both in terms of market ideology and market practice. And I think that this is now in significant decline. Globalization as a shared crisis of human development versus the carrying capacity of the planet on which we all live is rising, I think. This is going to be increasingly the principal subject matter of globalization. And it’s a very interesting question to which I will suggest various kinds of answers as to how these two things interact. In other words, will the shift towards a more environmental understanding of globalization work in favor of restoring the global market or will it work in favor of actually diminishing the global market even more?

If we turn to how we got to this point, I think here it’s quite a simple story. The economic side of globalization can be understood in terms of almost a dialectical process which has been going on for more than 200 years between the global market on the one hand and economic nationalism on the other. And there have been a number of very clear cycles here. We are in, I think, the fifth of these cycles.

- The first one ran from roughly 1840 to 1914 when the global market was dominant: free trade, the gold standard, and all of that. The first big outing of the global market.

- 1914 to 1945, a period of world wars, was a period largely defined by economic nationalism basically because it was war economies for the most part. And then in the 1930s, imperial economic zones.

- 1945 to 1972, the so-called Bretton Woods period, was one of compromise where, in a sense, putting it very simply, the global market was applied to trade but not to finance. So finance was restricted during this period. It was a kind of compromise between economic nationalism and the market because the understanding had been that the global market created too many difficulties in domestic labor relations and labor politics.

- From the 1970s to 2008, you have another period of the global market, the so-called neoliberal period, with extensive economic globalization. But this comes to a fairly abrupt halt with the big economic crisis in 2008.

And since then, we’ve been in a rather mixed period, a bit hard to describe, in which there don’t seem to be any good solutions. It’s clear that neoliberalism was overextended and unsustainable in a variety of ways. So there’s a question on the table now: how much of the global market do we want to keep and how much economic nationalism do we want to have? And there are arguments around those two things, and it isn’t very clear where we’re going to end up. So we’re in a sense in a period of transition around a discussion on those questions.

That’s where we are now, I think, on the economic side of globalization. The environmental side is quite different and has been, in many ways, not very closely related to the economic one. The consciousness of the environment as a global issue and as an understanding of globalization in the sense “we are all in the same boat” didn’t really get rolling until the 1970s. The Stockholm Conference in 1972 would be a good benchmark. By the time we get to 2015, there’s a broad global consensus that states and people have a responsibility to address climate change together in some way. So, there’s an acceptance of that responsibility, although there’s still a lot of argument about how to do it.

Since then, there has been a steady rise in the costs of climate change, not yet it seems significant enough to change a lot of people’s minds, but people are becoming more and more aware that climate change is becoming an ever bigger issue. The key question then is how do these things play into each other? Should global warming be addressed through the global market, or does the addressing of global warming require, in a sense, the cancellation or pushing backward of the global market? That, it seems to me, is a very big question.

If we move then to a more detailed close-up view of exactly the transition that we are going through now, it seems to me there are several broad factors in play at the same time, overlapping and interacting often in very complicated ways as this story works itself out. And I’ll look at four factors here.

The first one is that neoliberalism created a crisis of liberalism and the global market generally. It was overextended. Its political ambitions were unrealistic. It had too many costs in terms of instability, particularly financial crisis and debt crisis, and inequality, so that it undermined (itself) even in its heartlands, in the heartlands of liberalism in the West. Neoliberalism undermined itself because of its excesses and extremes.

So, there is a general crisis of liberalism going on at the moment, and China plays a very interesting role in that in the sense that China has managed to detach the market from the whole political and social package of liberalism. And that creates some very interesting questions and dilemmas for the liberal position, which is where the market idea originated. So, crisis of liberalism is one of the strands in this.

The second one, and quite a big one, is that I think it’s fairly clear that we are at the end of the era of Western dominance of world order. It’s not that the West is disappearing. It’s not like the fall of Rome or anything like that. The West is still rich, it’s still powerful, it’s still strong, and it’s not going away, but it is relatively weaker, and it is relatively less willing and indeed less wanted as a global leader. So, we have a situation, technically I would apply the name “deep pluralism” to this, where wealth, power, and cultural and political authority are all becoming more diffuse. So there’s no longer the concentration of power and status and influence that there once was to underpin a world order, and therefore the management of global society is getting weaker.

It’s not that there’s a lack of wealth and power around, but it’s distributed in a much more diffuse way, and there’s no agreement about what kind of global order there should be. The old great powers are basically fed up with the job of leading the world. Their electorates no longer support it. The new great powers don’t seem particularly willing to take up the task. So, there’s an under-management of the global order in play at the moment.

I think this is partly also a consequence of the fact that we are seeing a second round of modernization. There was a cluster of modernizations in the 19th century which stopped with Japan. So, Japan and then mainly Western countries were that first round, and then there was nobody succeeding in modernization until the 1970s. There was a whole century when basically nothing happened in terms of modernization. But in the 70s, the East Asian Tigers and China, and then a bit later India and others, have joined in and begun to be able to accumulate the wealth and power and political authority that goes with modernity. So, there’s a very big shift going on here, and we are kind of in the middle of that shift, and it explains a lot about why there is no consensus about what the global order should be.

To make things even more complicated and worse, and I will say something unfashionable here, we’re in a second Cold War, and we have been for at least the last four years. I know that there’s a lot of political denial of this fact, but by any reasonable definition of Cold War, that’s what we’re in. There are issues that are worth fighting about, but because of nuclear deterrence and other things, nobody dares to fight a war about these things, except of course the Russians. And that makes this a particularly dangerous kind of Cold War. And it is driving back economic liberalization at a great pace and also preventing any kind of cooperation and coordination on global environmental factors.

And then there’s the rising crisis of global warming which at some point will reach a tipping point in terms of how people see it. At the moment, it’s an inconvenience. It’s too hot, or it’s too cold, or too wet, or too dry depending where you are. But at the moment, this has not become serious enough really to change people’s behavior in a drastic way, and it’s a very interesting question as to what will have to happen in order for people’s attitudes to change. I don’t know the answer to that. It has to be something big. The flooding of New Orleans or New York or Bangladesh is not enough. It’s got to be something, probably, like the image of the Titanic here, because it has to be something big enough where a lot of rich people and a lot of property get destroyed all in one go, and then people will stand up and pay attention.

So, those four things are all going on at the same time here, and they interact in very complicated ways which makes it kind of impossible to predict anything very definitively. Let me then try and draw to a conclusion on this. It seems to me then that environmental globalization is only going to get stronger. It’s definitely going to get stronger in a physical sense that the climate is changing, and that’s now kind of hardwired into the coming decades and unlikely to change as a trend. Whether this will generate a more social and political form of globalization around it is a big question. Maybe it will, or maybe it will just add into the second Cold War and become yet another set of reasons for people to be divided and to disagree and not to be able to cooperate to try to address these issues.

Economic globalization, it seems to me, is not in a good position in this because many things are pushing against it to more in favor of economic nationalism and less in favor of the global market. So, the second Cold War–very much pushing more towards economic nationalism in all kinds of ways as countries want to reshore their supply chains and their industrial base. The crisis of liberalism–because liberalism was, in a sense, the intellectual fountainhead for the global market, this is also pushing or weakening the support for the global market. Anti-Westernism in the third world can often be mobilized against the global market as well. There’s a lot of residual anti-capitalism inside anti-Westernism, and that’s quite a big part of global politics at the moment. I’m happy to talk more about that in the discussion if anybody wants to explore that. And the weakening of global governance, there’s a self-reinforcing cycle here. International institutions, think of the World Trade Organization for example, are becoming less and less effective, less and less able to operate in this political environment of deep pluralism.

So, it seems to me the main, and I’ll finish on this point, the main hope for the global market, in other words, the economic side of globalization, is that somehow it is made to serve as the basis for a global embracing of sustainable development. So, sustainable development is where we have to go in order to address the environmental crisis and global warming. And that can be done through the market, but it can also be done against the market, and it seems to me that is the interesting political space that we have to play in if we want to carry on with a good measure of economic globalization. Thank you for listening.

Dialogue

Henry Huiyao Wang:

Thank you, Professor Buzan, for your excellent keynote and opening speech. And also, I’m very glad to be joined by Dean Liu Debin but also our friends from the Adenauer Foundation. Denis Simon is sitting behind, who was the former provost of the Duke Kunshan University on the American side. And of course, many think tank fellows and friends are here this afternoon. But of course, we are going to put it online. We have more people to watch this as time goes on.

So, Barry, actually you studied a very good topic. Of course, the topic for today is the outlook for globalization. We know globalization has been on the fast track. Let’s put it this way, since you mentioned the Bretton Woods system, the 70s that Asia took off, and China after that. But what has been seen now is actually the escalating of geopolitical tensions. We see also the big power competition has been intensified. When I was talking to Graham Allison just about two months ago here, he was also thinking of how we can avoid Thucydides’ trap. Also, Joseph Nye was telling me that maybe we are at the lowest cycle of China-U.S. relations. Hopefully we could get out of that. Maybe we can reach a new equilibrium in another 10, 15 years’ time. But right now, we are locked into this competition phrase. As U.S. Secretary Blinken put it, we are in this competitive mode for a very long time.

But I agree with you. You mentioned very well in your keynote speech here. I think I totally agree with you that we are in the middle of a shift probably for purely market economy to a more dynamic, more complicated, war situation now. For example, the human security is less emphasized now. We will talk about national security more. Also, economic globalization was not emphasized. I think all those really present enormous danger to all of us.

What I can see now is you give a very good highlight of the challenge we are facing and also the focus we are missing. We actually haven’t focused enough on the human security, particularly not on the climate, on the environment, on those common threats that mankind face. So, in your talk, you highlighted the shift from economic to environmental concerns as the defining aspect of the current globalization. So, as a permanent leader in the international relations arena, which you have emphasized the society approach, what do you think of this shift impacts the theory both broadly and in specific terms? What would be the next really big outcome of this shift? Perhaps you can give a bit more elaboration on that.

Barry Buzan:

I certainly agree that the language of world politics has shifted into a geopolitical language, and it seems to me that is one extremely good indicator of a second Cold War. When people start to talk in geopolitics then you’re in a cold war. But whilst I say that, I think when you use a phrase like “locked into competition”, that raises alarm bells for me.

I am not a fan of realist thinking about competition because realism is a self-fulfilling prophecy. The more people who believe what the realists say, the truer what they say will be because they say conflict is inevitable. If you believe conflict is inevitable, then it becomes inevitable because you believe that and so does everybody else and their behavior goes that way. So I think one has to be extremely skeptical when listening to realists who make that kind of argument and say conflict is inevitable, we are stuck with this, there’s no way out etc. There is always a way out. It just requires a different kind of politics and a different kind of mindset.

The realists may actually be right most of the time, but they are not right in principle. By arguing the way they do, they close the door to any other possibility. So, if you believe the realists, then there’s nothing to discuss here. It’s just going to get worse and there will be more and more conflict and climate change will play into that conflict. It will divide people, add to the reasons why they fear each other, are suspicious of each other, and play against each other in these kinds of power games. You can take that point of view if you want to. It’s a very easy, in some ways, quite a comfortable point of view. It just happens to be wrong. So I will start from that position and I need to be clear about that.

The realist position is now having a moment in history because as I mentioned, liberalism is in a degree of crisis. And liberalism has been the main counter to realism for the last century and a half. So, the decline of liberalism puts a burden on those of us who want to encourage globalization in its positive way meaning that as a species and as humankind, we think like a species and behave like a species when we are confronted with a common problem. So liberalism has been the vehicle for that, and liberalism is now in some disarray.

So I think the point I was trying to suggest about climate change was that this might be something which can be built upon. It’s a new factor in the game and it puts us all in the same boat. None of us can fix it by ourselves, but we will all bear the consequences of it if it isn’t fixed. And therefore, it’s a very big collective action problem that doesn’t require you to be a liberal. It just requires you to recognize that you’re in the same boat as everybody else, and that the boat is sinking, and that something needs to be done about that.

So it seems to me if one is looking for the space for political action, it’s the interplay between what [inaudible] say that climate change is good news, but there is at least some good political potential there for what might be done. Now you ask me what comes next, and well, in all honesty, I can only say: “I don’t know” because climate scientists don’t know what comes next either. So, I have a very strange vision of optimism here which is to say that what we actually need is for climate change to get steadily, and I underline, steadily worse because the other alternative is that climate change gets suddenly worse. And if it gets suddenly worse, it may take us outside our capacity to do anything. So, if you get a step level change into a hot house or something like that, (it’s) possible but not possible to predict with any kind of certainty. So, we don’t know. If we’re lucky, it will get steadily worse, and that will pressure us into doing more and more collectively. That’s the best I can say.

Henry Huiyao Wang:

Thank you, Barry. That’s excellent. I think you made an excellent point, and absolutely, I agree with you. Some people actually propose that competition is the theme, and there was overemphasis on the competition, less on the cooperation. And also U.S. has made China a strategic rival, and EU has made China a systematic rival. If that is the case, as you said, there could be self-fulfilling prophecy China does become a rival and that that is really not a good thing for the world.

So I would really think that the world, as you said, (we are) already in the second Cold War now. It’s probably happening already. And then we have actually just finished the first worldwide virus war, COVID war. We just finished that. There’s about 20 million people who lost their lives during this first worldwide virus war. We haven’t really drawn the lessons on that. We did not collaborate. So I totally agree with you that probably the things that can glue us together is this climate threat. We need to build up this new climate globalization, as you suggested, that we find a common ground and then we can work together. So, I agree with you. This is probably the low hanging fruit that really can combine the mankind together. We are really talking too much about national security which is drive(ing) up all the military budget, and then escalating each other, and we will be really fulfilling the self-fulfilling prophecy that we bound to be competitive and bound confrontational and conflict. That’s something we want to avoid.

So, what I think the next draw-in I would like to ask you is about in addition to the climate is: What about AI? Artificial intelligence is so uncertain. It’s something new. The U.S. is doing that. China is doing that. A few weeks ago, we had the German ambassador and the French ambassador come to CCG. We had a dialogue together, an event about EU-China collaboration on how to avoid risk of the AI. And a few days ago, Chinese representative at the UN proposed how the countries work together to harness the AI but void the risk. That has been unanimous passed by in the UN General Assembly, including the U.S. So, in addition to the climate — I mean that’s something can really bind us together — what about this AI which is so unknown? Human beings could be the slaves of AI in the future if they’re not careful, or if automation decision (has) been built into AI, they could destroy the mankind. So, what do you think about this new area that there could be an AI globalization happening that we didn’t realize?

Barry Buzan:

Good questions. I think in terms of competition versus cooperation, I’m not sure that’s exactly the right way to pose it in the sense that competition could work. So if it could be arranged so that the great powers competed with each other to promote sustainable development and control of climate change, that would be a very effective way of doing things, perhaps more effective than trying to actually agree a cooperation. I’m not quite sure what would be necessary to make that work.

As far as I can see, China, for example, is a strange case here because in some ways, quite a few ways, its domestic environmental policy is really rather progressive: lots of nuclear power, and solar power, and all of that kind of stuff. So, in many ways domestically, China is doing the right thing, but there doesn’t seem to be any connection between that domestic policy and its International policy where China tends to be more obstructive than helpful on the cooperative side. It sides with the third world saying basically it’s all your fault; the West, you pay for it and we don’t care; let the boat sink. So competition might be the way to go. It might be easier to do it that way.

The COVID example is an interesting one. I agree it’s worth looking at because it’s a demonstration case of a collective action problem and how we did. It seems to me a mixed picture. In some ways, the whole COVID crisis pushed more for economic nationalism because of the supply chain issue and people hoarding vaccines and hoarding the protective equipment and all of that. So partly, we reacted badly and competed about it. But underneath that, there was actually quite a lot of cooperation going on, particularly in the scientific community, I think. Not perfect but substantial. I mean the speed with which vaccines were rolled out was really rather astonishing if you think about that historically. I mean, within a year or so, there were good vaccines available and they were being mass-produced, which is amazing that that kind of problem could be solved that quickly. So scientific collaboration, while not perfect, was a big part of that. So, it’s a mixed picture. You get some good sides and some bad sides.

Several points on AI. I think the one thing I’m absolutely sure about AI is that we are going to have a lot more of it very quickly, and it is absolutely unstoppable. It’s simply because so many very powerful factors support it. Militaries everywhere are absolutely keen because they know if they fall behind, they are lost, and that’s a very standard situation. In military establishments, they’ve got to keep on the technological edge. Corporations are desperate for this because they think there’s money to be made out of it. Scientists are very keen on it because there are careers and Nobel prizes and all sorts of other things to be got out of it. The public is increasingly keen even though there’s some negative associations with AI, but when you have your first encounter with ChatGPT, you go: “that’s amazing!” So, people are enthusiastic about it because in many ways, it’s an absolutely wonderful transformational technology.

So, many, many factors are pushing in favor of this, and it is inconceivable that it would be stopped. So that will have good sides and bad sides as most things do. It might, on the good side, it might help us with the climate change problem because it increases one’s analytical capability hugely. You can see that already partly on the vaccine issue — the application of AI to searching for new kinds of drugs and new kinds of chemicals. That kind of search capability for scientific understanding is really enhanced by AI, and that’s going to increase by leaps and bounds. So, it may be that this is one of the things we absolutely need to solve the problem of climate change because it will enable us to analyze better the things we can and can’t, and should and shouldn’t do.

AI is going to be part of the general militarization that’s going on with the second Cold War, inevitably. You don’t need to be any kind of great expert to follow the literature on that. Just read the military analysis in The Economist and you can see exactly what’s going on there, and very quickly and very powerfully. So that’s a negative side there, but I don’t think we can do anything about that. The forces pushing that are too strong.

The other element I think I mentioned there is surveillance AI is going to very much amplify surveillance societies. Now, we’re all living in surveillance societies. It’s done differently in different places. Here in China, the government does most of the surveillance. In the West, it’s corporations that do most of the surveillance, but the government in the West can always get the information from the corporations if they want. So, the systems are different, but in some senses, wherever you are and whoever you are, everything about you will be known and traceable. And this has all kinds of implications, social and political, which are bigger topics than we have time for here.

How and whether that might play into the climate change question is interesting because if everybody’s behavior is, in principle, public, that might become a useful factor in how climate change is addressed, how the behavior of the public is changed, controlled, or manipulated in whatever way to serve the goal of sustainable development. That’s a very complicated question and I’m not exactly sure what it would look like, but it seems to me that’s a very likely area where AI will play a big role.

Henry Huiyao Wang:

Great. Thanks Barry. Absolutely, you mentioned quite a few great points. I agree with you. I think cooperation should probably put it in more constructive mode which it does benefit competition as well.

One of the examples I can give is that there’s a huge global deficit on infrastructure worldwide where China realized that and China has actually put forward on the Belt and Road Initiative to really benefit the Global South countries. China has already invested 1 trillion U.S. dollars in about 3,000 projects across the developing countries. So, 70-80 years later, then we had U.S. proposed “Build Back Better World”, a U.S. style infrastructure project, and the EU put EU Global Gateway, and India has put India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor. Because China did that, everybody’s like: “Oh, there’s a big deficit on infrastructure”, and then they actually come up with their respective plan.

But the key is that can this plan be collaborative and cooperative? We have the World Bank; we have the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank; we have the Asian Development Bank, African Development Bank, European Development Bank. Can they really work together? Can we have an Olympic-style cooperation?

Another example I can think about is, you talked about environment. We are facing environmental challenges now, but 10, 15 years ago, Beijing was heavily polluted. There was smog. Foreigners come told us, “it’s so polluted that we don’t want to come to Beijing.” And the U.S Embassy started to monitoring the PM2.5 on the roof of the U.S Embassy in Beijing, and then they announced that on a daily basis. First, Chinese was not happy about that, but later on they accept that, and they made a huge determination to change that. So, a decade ago, Beijing used to be heavily polluted by the automobile, diesel and gasoline driven. But now, half of Beijing automobile is EV, and then China becomes the leader in the EV Market, solar panels, and batteries. And Beijing got cleaner. So, that’s another thing through competition.

But then, we have been facing all those tariffs: 100% from the U.S., 20% to 38% from the EU blocking Chinese EV cars, even for the climate, something that is so common that we want to change. For example, the International Atomic Energy Agency forecast that (if we were to) follow the Paris climate agreement, we need to spend $ 4.5 trillion U.S. Dollars on green spending annually, (but) we only spend 1.8 trillion. And the world needs 800 gigawatts of green power, we only do a quarter of that, far from oversupply. Sometimes politics also block this kind of process. Even though we wish to have Olympic-style cooperation, politically, we cannot do that.

So, how do you think we can solve this dilemma that we are facing now? 20 years ago, China was blamed for not doing something. Now, China really takea a big strike forward and did quick upgrading, and then (they said) :”you are doing too much”, “you are oversupply or overcapacity.” So, it’s really in a difficult situation. How can we solve that? Or maybe explain to the world, even with this climate awareness, we have to work together.

Barry Buzan:

On the question of the BRI and its imitators, the kind of global financial infrastructure as it were, and how it relates to development, that’s not an area I know a lot about. So I would put the question back to you: are these rganizations or how committed are these organizations to sustainable development? Always when I’m looking at these kinds of questions, I’m looking for where’s the scope for political action? What can we still do something about it? Where do we still have meaningful choices about how to influence things? If these outfits are not fully committed to sustainable development, then they need to be pressured in that direction. I don’t know the answer to that question, but perhaps you do in which case you could say.

The case study of Beijing air quality. I’m one of the beneficiaries of this particular change. I remember the days of Beijing smogs and all of that. I was born in London in 1946 when smog was an extremely serious problem in London, and it actually played a big role in the life of my family. My family had to immigrate to get me out of London because the doctor said, “If you don’t move, you will lose this child.” They are good parents, therefore they moved. And therefore, the rest of my life kind of followed from that. So Air quality has been a big factor in my personal story, and I’ve been to Beijing often enough to appreciate the change. It’s blue sky. It used to be “You never saw blue sky from Beijing. You were lucky if you could see the building next door to you.” So, a big change, I agree.

I also agree that — and here I’m going to sound a little bit like The Economist–actually the best way forward would be if China were allowed to export its green technology more or less freely regardless of whether other governments think that it’s subsidized and therefore the trade is unfair because the the Chinese companies get all kinds of cheap loans and etc., and therefore nobody can compete with them because companies elsewhere don’t get those kinds of support. But even so, I mean on free trade principle, the argument would be if the Chinese want to sell these things at less than the cost of production, then we should buy them. You can bankrupt yourselves, saving the rest of us as it were, and that’s fine because it’s still good for us. We get the same thing cheaper.

But the problem with that is there’s a good if you’re a pure economic liberal, you can think like that, but most politicians are very long way from being a pure economic liberal. They don’t think like that. They have to think about the security side of things. And there’s no question at all that the second Cold War has poisoned the atmosphere about this because a lot of this kind of trade has been weaponized to the extent that trade produces dependencies. And you saw this in the COVID crisis.

The standard liberal argument about trade is that you don’t have to worry about security because there are always lots of suppliers. If you don’t produce this thing yourself, several other people do, and therefore you get to choose who you buy it from, and that’s where your security lies. But in the case of China, China, as it were, monopolized a certain number of industries by subsidizing them, an d therefore nobody can compete with them, and therefore there’s only one supplier. China is more or less completely ruthless in weaponizing trade dependency. It’s very quick to punish people if they do things it doesn’t like, and if there’s a trade dependency there that they can be punished with. Think of Chinese relations with Australia, for example, or Canada, or Norway, or a dozen other countries with whom China has tried to use trade dependency for political purposes. That tendency was there already.

And now that we’re in the second Cold War, the whole security issue becomes politically much more prominent, and the security issue will always override the trade logic. So basically, politicians now have to answer to populations who say we do not want that COVID thing to happen again. We do not want to find ourselves in a crisis where we find even a big country like the U.S., we don’t produce this stuff, and therefore we’re completely dependent on somebody we think is our enemy for the supply. No, that’s not politically acceptable. So, the cold war is poisoning the trade atmosphere there, and the logic is perfectly sound. I agree that in an ideal world, that should happen. Everybody should buy that technology as quickly as they can, and that would help green development faster than anything else, but it’s not going to happen because the political environment that supports it has collapsed.

Henry Huiyao Wang:

Well, it’s very unfortunate to see that. That’s right. I remember every year when they have a COP27 or 26, or even now going to be 28, there’s a complaint that there’s not enough financing to really help the developing country to fight climate change. If China can produce solar panels cost-effectively and cheaply, it’s indirectly China’s contribution to this money pool to fight climate change to help the developing countries. So, the Cold War mentality and these kinds of series are really blocking people from using each other. But I think, for example, 90% of China Fleet is composed of Boeing and Airbus. China didn’t say, “Because they are produced in the U.S. and the EU, that’s oversupply or over capacity.” China still buys a lot. So, absolutely, this Cold War mentality doesn’t really help. And then I think for people in the academia and think tanks it is really how we can really get more focus on this and reduce the tensions and the mistrust between the major countries.

So, I would like to think now, for example, we are seeing the developing world is getting really big. We are having a BRICS Summit coming soon, and last year, the BRICS Summit doubled. That’s also a new wave of globalization because they want to join the BRICS because they see the economic benefit. So, maybe we are living in a more fragmented world now. A unipolar world is gone, and then the multi-polar world system is not there yet even though the multipolar countries are coming up. Also, there are midpowered countries and many countries like that. So, what do you envision? Maybe we open after this to our audience to talk. What do you envision as a future globalization structure? Because the unipolar war is not there anymore and yet the multipolar world hasn’t really been formed or shaped like a new Bretton Woods moment. And the UN has sometimes become marginalized and not really effective. So, in this chaotic world, what’s the way out? What’s the path out? And how China, the U.S., the EU, Global South countries, and mid powers can work together? I mean climate is certainly the common cause for all of us to work together. AI is another one. Maybe there could be more opportunities. Human security, probably; Global South. And also, we’re facing war now. That’s really getting us into a very dangerous situation. So, what’s the way out? That would be my question.

Barry Buzan:

I agree the aircraft market is also one-sided. I’m not quite sure whether that’s to do with subsidies possibly or whether it’s just extremely difficult to produce. That kind of aircraft engine and aircraft landing gear are extremely difficult technologies to master, and only a few leading-edged countries have done that. China will get there, but it will take time.

Let me talk a little bit around your unipolar and multipolar world. I’ve never liked unipolar. The world was never unipolar, and it will never be again. So, we can forget about unipolarity. These are both realist concepts. Basically, unipolarity says no balance of power. Multipolarity says the balance of power. And multipolarity implies that the competition amongst the great powers is to dominate the world because that’s the way it used to be. But that’s not the situation we’re in now. The situation we’re in now is that nobody wants to run the world. Nobody wants to take responsibility for it. I actually believe the Chinese Foreign Ministry and the Propaganda Department when they say they don’t want to run the world. I think that’s quite right. The Indians don’t want to run the world; the Americans don’t want to run the world; I mean what is Trump about it if it’s not deciding we’re not going to run the world? Let the world run itself. The Europeans might like to run the world but can’t. The Russians would definitely like to run the world but nobody else would let them anywhere near such a job, and they have not the capacity for it anyway. So, we’re in a world where none of the old great powers and the new great powers want to run the world, and that’s the problem.

The world we are leaving, the Western dominated world, was one in which the kind of globalization was defined or understood in a universalist way, in a kind of liberal way, because for a long time, modernization was equated with Westernization, and that was a big problem for China, Japan, and other countries. It was always wrong. Japan modernized very successfully but it certainly didn’t become Western. I’ve been to Japan plenty of times, and I can tell you it is not a Western country. It’s a modern country for sure, but it is absolutely not a Western country, and China is going down the same route. It’s modernizing, definitely a modern country, but definitely not a Western country. So, what we’re going to get is a kind of more and more universalized modernity spread more widely through the world, but with different interpretations and different understandings.

The liberal understanding, which has been the only understanding of modernity for a long time, is now giving way to a world in which it is perfectly obvious, led by Japan a long time ago, though nobody recognized it. The Japanese were the first people who modernized without Westernizing. They adopted some Western elements but they didn’t become Western. They didn’t surrender their own culture. And that will be increasingly the case, so we will be in more a world of diversified modernities which will have different kinds of societies and different kinds of politics attached to them.

So, the world that we’re heading into is going to be a decentralized world compared to the one that we’ve been in. It will be decentralized in terms of wealth, power, and political and cultural authority, much, much more than it has been during the Western period when there was just one central power wealth and culture.

We’ve never been in a world like that before ever. It’s an entirely new thing. We’ve been in a world which had many different cultures and civilizations in it before, but then they weren’t very closely connected with each other. China was quite remote from the Mediterranean cultures and all that, and the Americans even more so. Now we’re in a world in which cultures are different, and they are increasingly equal in terms of modernization, but they’re extremely interdependent both economically and also now in relation to climate change and kind of planetary management.

That’s a new world. And I think it’s there. Whatever assumptions you make about it, you have to start from the idea that it’s going to be a relatively decentralized political order, and the question will be whether that order can agree that it has some common problems which need to be dealt with together. It is not going to be aiming for a universal political order around liberalism. So the kind of Francis Fukuyama model is gone. This new model is something completely new, and we have to try to work to find the way of respecting the differences and operating with the differences but being able to cooperate when we need to for collective purposes.

Henry Huiyao Wang:

That’s a great comment. I think a decentralized world is the right world, but I also probably see there’s regional decentralization too. There’s United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, European as a block, ASEAN, and RCEP, the largest Free Trade Agreement happening, and BRICS countries are forming more tightly now. So, there could be a block of different kinds in this world happening. How to really peacefully cooperate together while we’re decentralizing is still a new challenge. So we find this discussion very fascinating, and I would like to open it now to our guests. Maybe first I’ll invite Professor Debin. You also had a long relation with with Professor Buzan. You have also been the Dean of the International school for so many years. Perhaps you can share your observation and comments please.

Q&A

Debin Liu:

Thank you very much Henry. I think it’s a very good dialogue. I learned a lot. I think if we ask people to give one keyword to put the international issues right now associated with globalization, you’ll find a lot of problems, questions and issues that you want to know. But first, I would like to ask Barry a question: what about the political election in Britain? He just came from London. When he was on the way to Beijing, the conservatives still controlled power. When you head back, politics totally changed. We know Britain is one of the leading powers in the Western world, so what kind of change could take place in the future years with the relationship between Britain and the EU, between Britain and the United States, between Britain and China, and between Europe and globalization? This is the question I want to ask.

Adenauer Foundation:

I took his class in International Security 15 years ago at the London School of Economics. It’s the first time I’ve seen him. He looks the same, hasn’t changed a bit. Also, his thoughts are still as interesting as they used to be.

One question I ask myself is also how do you see Europe’s role, the role of the European Union in this future era. I would totally agree and it’s interesting to have you here as an academic because in our field, when we talk to politicians, nobody’s actually saying that it’s a new Cold War. But I would totally agree what I found very striking about our German China strategy was that we are always talking about China as a partner, and then we have not many fields to name, and we always say climate change. But I would totally agree with you too that at least right now, this is an area of competition, and this might not only be bad news because when it comes to solar panels, at least those we are still buying for a very cheap price from China now, this might help all of us. But at the same time what I’m seeing now is also a divide when it comes to technology. That’s my fear between the so-called West and China. I believe that’s also where we are heading, and I don’t know if that is going to be something good. I fear it’s rather something bad when I see that the free transfer of technology is simply not happening anymore.

Denis Simon, Chairman of the Alliance of Global Talent Organizations, Advisor to the Global Young Leaders Dialogue (GYLD), and former Executive Vice Chancellor of Duke Kunshan University:

Actually, I was kind of perplexed a bit. Henry, you said there’s a kind of imperative nature to addressing global climate change, dealing with AI, and a number of issues like that. And then you said, but the problem is the politics gets in the way. I’m wondering, maybe the politics is, in fact, the show. The game is really not either global climate change, or AI, or whatever public health, or COVID. It really is politics. Then, the question has to become “why did the politics suddenly change?”

And then you look at the bigger picture: was this age of globalization the aberration in a world in which — even though I know Professor Buzan said he doesn’t like the realpolitik kind of model, but maybe the world is, in fact, much more Darwinian than we’d like to believe. The aberration really was the last 25-30 years in which we did things in the world in a way that we almost had never done before. And I know there’s a lot being written about the roots of globalization going back into ancient times in some cases etc., but the reality is that, in fact, maybe the nature of the current political situation is much more the norm, and that the politics itself hasn’t really changed very much. Then we have to ask ourselves what happened during that short period in which globalization proliferated that made it all possible because somehow we let that go and get out of the cage or whatever where it was, and we’re back to where we we had been.

So, whether we call it a new cold war or whether we call it something different, the reality is that we may be leaning back to the norm. I will tell you if you ask an American perspective: if Donald Trump becomes the president again, it will be even more so the norm. The philosophy of “Make America Great Again” is not very different than what a lot of other countries are talking about their own Renaissance of bringing back the greatness of their own country. I’m just wondering when you say politics gets in the way, I would push harder and say “the politics is the real game of it all.” And how can we restructure or reconfigure the politics so it can allow for the kinds of things that happened over those last 25 years that seem to no longer exist?

Barry Buzan:

A modest set of questions. About the UK election, thanks to the great Chinese firewall and my inability to make my VPN work, I don’t know the outcome of the UK election because all of my connectivity is gone. I know that Labour won but I don’t know by how much. So if anybody knows, tell me afterwards because I’m quite curious.

I would dispute your characterization of Britain as a leading power. Britain is now a rather minor power of extremely little consequence as a result of the last government having taken us out of the European Union. The ridiculous slogan of “Global Britain” in a world that is deglobalizing very fast—that’s how wrong they got this. The country is not quite bankrupt but close, so it’s very heavily indebted. The incoming government, whilst it will want to have easier relationships with the EU and it will want to try to address the problems of low productivity that have plagued Britain for a long time, it doesn’t have any money to play with. There just isn’t money there. So, they’ve either got to raise taxes which would be very unpopular or not do very much, which is the more likely outcome. So, I guess the main good news is that relationships with the EU will be easier because there isn’t that kind of big ideological wing in the Labour Party that is obsessively anti-european as there is in the Conservative Party. So there will be some changes. They will matter very little to the rest of the world, although it will be a bit easier with Europe.

On the European question particularly: how will Europe operate in a deep pluralist world? I think the EU is having to learn to think geopolitically, which it has never done and never wanted to do before, but has now been thrown into this by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. And I take that the Ukraine war is extremely serious. It is a very, very dangerous war because it’s basically a war about a civilizational boundary, and the stakes are extremely high on both sides. If Russia loses Ukraine, then its whole claim to be a kind of Slavic Orthodox trans-Eurasian civilization collapses. Gone. If Europe loses Ukraine, then the whole rhetoric about Europe is being in decline, no longer consequential, the third world rhetoric, and also–I’m sory to say–China and Russia participate in this rhetoric of Western decline, and all of that will then be reinforced. So, the stakes for both sides are extremely high. You are seeing the boundary between the EU and the Russian sphere being extraordinarily militarized and very quickly. The idea of Finland and Sweden joining NATO after having decades in one case and centuries in the other case of strong traditions of neutrality is absolutely transformational. It’s mindboggling, in fact.

So this is a very, very serious war. Neither side can afford to lose. The likely outcome is that it goes on and on and on for a very long time. And the big immediate question is what happens if Trump wins the election? Because Trump is a completely unpredictable factor but mainly it seems that the Russians have something on him, and therefore he’s a Russian puppet. He plays to Russian foreign policy interests and uses Russian foreign policy tropes.

I think the curious thing about Trump, getting on to the third question, is Trump and his slogan of “Make America Great Again.” Trump has, I think, utterly and totally failed to realize what made America great was not only its material, technological, and cultural strength, but the position that it held in the world where it had a lot of friends and allies. In other words, it had a strong social position and had cemented that with a whole string of intergovernmental organizations and multilateral processes and everything. That is what made America great–that the whole range of other great powers were prepared to go along with it and accept its leadership because the terms were okay. Trump just doesn’t get that at all. And therefore, he is throwing away, in my view, about half of American power. He is making America much less great than it was. And if he gets in again, the damage done the first time around was sustainable; the second time around may not be sustainable. So, it will be a very different world that unfolds as a result of that.

On the idea that politics is the main show, that’s a very good question, and a very nice way of putting it: was economic globalization an aberration? This, I think, is a very clear demonstration of what I was saying about realism earlier. Realism is a really comfortable place to be because you never have any doubt about anything. You always know that the world is going to revert to being nasty and conflictual, and therefore you just have to go along with that. There’s no puzzle about it. We had this long aberration, remarkably long, and therefore a bit difficult to explain a way in which it appeared that some quite basic things about the world had changed. And I think that takes us back to the globalization theme. You know, globalization is not dead, and it may be, in some senses, inevitable. We are now living in such a densely packed world, something that we have never lived in before. Some elements of globalization simply have to be there. We can’t exist in this world any longer without them. It would reduce things to complete chaos. So, we are still struggling to find what the balance is going to be between a globalized economy, parts of which are still there, and economic nationalism. We don’t know what that balance is going to be, but it’s not going to be 100% economic nationalism. If that’s what Trump does, then he will simply impoverish America, and everybody who’s anti-American will cheer that because it makes America less great.

Henry Huiyao Wang:

Great questions and a lot of feedback. I agree with you. The “Global Britain” Theresa May put forward. I was just with her about two weeks ago in Austria. She now thinks of Brexit is because, at that time when people voted, they were not satisfied with the government. They just anchored on the Brexit to leave the EU. But looking back, it’s probably a terrible mistake. I agree with you, so we have to fight that back. For the EU, I would think now the EU is so important. Rather than totally one-sided, it could be really instrumental in mediating China-U.S. Relations in the middle so that we still have a multipolar world, and multilateralism can continue. I agree with you that the international social capital that the U.S. used to have is because of so many webs of global organizations and the global Bretton Woods system that can sustain that. And if they really detach from that, the U.S. impact will be greatly minimized. Now, we have the second round.

Journalist from CCTV:

I’m a journalist from CCTV. I have questions for Professor Barry. The first one would be, how do you view China’s role in improving the effectiveness of global governance? And the second one would be, since globalization and global governance face multiple problems and challenges, how do you view the role of multilateralism in global governance? And the last one would be, what will be the trend of globalization in the future? Thank you.

Another journalist:

My question is maybe very easy, but the answer might be difficult. Just about globalization: we saw many results of the election in the world just like France and Europe, and maybe just like the other guys think, Trump will come back. So maybe now globalization faces some challenges. Do you think globalization is that and many people didn’t believe in globalization?

Wang Xiaofeng, CCG:

Thank you, professor, for coming here to share your view with us. My question is, you introduced the concept of environmental globalization. As you can see, if economic globalization is driven by cost efficiency or comparative advantage, what are the fundamental rules or the principles that underpin environmental globalization? Can it lead to or encourage more cooperation? Because inside the cooperation, as you can see, the countries are vying with each other for the dominance in energy transition. So what are your thoughts? Thank you.

Barry Buzan:

First to your point about will the EU be able to mediate China-US relations. I would think potentially that might happen, but not until there is some kind of resolution to the Ukraine war. From a European perspective, China is now deeply implicated in supporting Russia. I know there are disagreements on that. I’m just saying that’s the perspective.

Henry Huiyao Wang: The perspective is there, but I do think China has a huge influence and impact and an enormous role to play in mediating this war between Russia and Ukraine. And so vice versa, China can help the EU, and the EU can help China. So I think there’s enormous support from each other.

Barry Buzan:

But the present situation is that the second Cold War, driven by the war in Ukraine, has pushed Europe on side with the United States. So, they now both think that they are against China and Russia and that China and Russia are, in effect, an alliance. I know China doesn’t have alliances, but….

Henry Huiyao Wang:

No, I don’t think so because if you look at the substance, Barry, China said all the things that support the EU. China says the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Ukraine should be respected. President Xi told Olaf Scholz that no nuclear war should be fought in Ukraine. If Russia cannot fight a nuclear war, what power does it have? And then, when President Macron came, President Xi called Zelensky, and China had an envoy to mediate already now among those countries. China has proposed a peace plan with Brazil and another 40 Global South countries. So the only (reason) China hasn’t gone to 100% position for the EU on Russia is because China wants to save little face to Putin so that when the time comes, China can intervene. But on the other hand, there are some people in China who think if China is doing too much, after the Ukraine solved, they’ll all chase after China. So, they view China as rival No.1, actually, before Russia.

So, you see, China is in a dilemma, but I know China wants to help, and China doesn’t provide weaponry. China does the normal trade with Russia. But in the Western press, that has been always interpreted as that China has been so strongly supporting Russia, but not necessarily. If China provided weapons to Russia, Russia probably would have made a big headway already. China does not provide weapons, whereas the U.S. and the EU provide weapons to Ukraine. So it’s totally true that China was not in the same position as we support Russia as others.

Barry Buzan:

We should probably agree to disagree about this. But I think the main point is the EU is not going to be a mediator between China and the U.S. while that war is going on. So, until it’s settled, it’s going to happen.

On the question about China and global governance, I think the interesting question there is: China is finding its place in global governance. It’s interesting about multilateralism, and multilateralism is what the Americans invented. The American order is now disappearing, but multilateralism isn’t disappearing. So it’s a kind of principle, realism notwithstanding. It’s a principle that has taken root. And it’s a way of doing international business that it looks like it’s got life in it. Yet China, I don’t know a lot about this, but China was reasonably cautious and slow to get itself involved in multilateralism and intergovernmental organizations. So for a long time, it seemed to sit and watch and learn how things work. Now it seems to be in a next phase, where it’s interested in getting its people in positions in various intergovernmental organizations so that they can influence things and shape agendas. And that’s already been quite effective.

I think, in the longer run, a part of this transition that I mentioned between a narrowly based Western dominated world order and what I called a deep pluralist world order is going to require what will be a decades-long process of change, either reform or replacement of many intergovernmental institutions. So, you see already things like the Asian Infrastructure Bank, BRICS Bank and all of that. Those kinds of organizations are the beginning of that process. They’re basically saying, if you won’t give us the status in the existing institutions, we’ll set up our own institutions and compete with you. And those become bargaining chips for reform in places like the World Bank, the IMF, and the World Trade Organization.

So this is going to be a decades-long process. It’s not going to happen quickly, quite what will happen with the United Nations and the Security Council. I mean, China is a conservative member of the Security Council because China is in a good position there, so it doesn’t want to let the Japanese, Indians, Germans, and anybody else into that privileged club. But that club is now ridiculous. Britain and France have seats on the Security Council, P5 seats. I mean, that’s just insane. So the EU should have that seat, and too bad for Britain that they left, but that institution is in very serious need of reform. How that’s gonna be done: we need institutions that reflect this new distribution of wealth and power and cultural and political authority, and it’s gonna take a long time to get them. So, that’s gonna be a process that will go on over many decades. And China will, of course, be a major player in that as it has already become.

Is globalization bad? Well, like most things, it’s good and bad. You can find globalization has been extraordinarily efficient in some ways in spreading wealth and power, and the principal beneficiary of that has been China. You just have to look at what happened to the Chinese economy as it were let into the Western world economy, it boomed. And hundreds of millions of Chinese people became middle-class, people like yourselves, which wasn’t the case before. So for very large numbers of people, that period of globalization was profoundly possible. For a whole bunch of other people, it was profoundly negative because they lost their jobs and found themselves priced out of markets or became dependent on supply chains that were not reliable. So, it’s a complicated question, which has big positives and big negatives. As I say, this is part of a long cycle, almost a dialectic between economic nationalism and the global market, of which we are now in the fifth cycle. And we’re casting around once again for how do you get this balance right. Too much global market is unsustainable. Too much economic nationalism is unsustainable. You have to have some kind of balance between the two, but how you do that balance and how you agree on doing that balance, we’ve lost that for the time being, and that’s what we’re looking for. So I don’t think you can make a grand judgment about whether it’s good or bad.

I didn’t quite get the question about the winter of global economics. I mean, yes, the global economy is not in as good shape as it was a while back. But then again, a while back, there were big financial crises and debt crises and all that kind of things. So, the global economy was not organized in a sustainable and optimal way, and that seems to be the problem. If you look at this pattern I describe, hardly any of these phases last more than three or four decades. So too much of one, too much of the other is unsustainable. Bretton Woods was the first attempt at a compromise, but that was unsustainable as well because it had a design flaw in it. It was dependent on the U.S. dollar, and that meant that the U.S. eventually built up big trade deficits, which became domestically unsustainable. So that system didn’t work either. So if any of you have got a good idea about how we balance economic nationalism and the global market, now would be a time to write it down and publish it because we are in significant need of such ideas.

The last question on environmental globalization and what would be the fundamental principles of that. I think if you’re interested in that question, it’s worth investigating the work of a group of people who identify themselves as Earth System scientists. This is mainly natural scientists, and their campaign is to use the skills of the different sciences represented in them to try to work out what the limits are and how many of them are. There are about 15 or 16, I think, in their present set of global planetary physical limits affecting the global planetary systems. How much CO2 is there in the atmosphere? How much nitrogen is there in the water? How salty or not, or acidic or not are the oceans and a number of other measures like that. Most of these things are measurable. So, this group of people has identified a series of thresholds saying if you go over this threshold, and we are already over two or three of them, you’re in deep trouble because the planetary systems begin to break down, and therefore, the support on which humankind and the rest of the biosphere depends begins to cease being supportive and becomes more and more demanding as a place to live.

Basically, the underlying philosophical drift of environmental globalization is that human development, however you understand that, and whether you think it’s about catching up for the developing countries or about continuing to develop for those already at the cutting edge, it has to be sustainable. It’s gotta be sustainable within the carrying capacity of the plant. Because if it isn’t, then we are going to overwhelm the carrying capacity of the planet and undermine the conditions of our own existence, and possibly quite quickly. So we don’t yet have a very clear understanding of how all of those planetary limits interact with each other and at what point you might get a sudden tipping point, like a catastrophic tipping point where there was a big change very quickly that was very hard to reverse like, say, 10-degree temperature rise if you’ve got a sudden release of large amounts of methane into the atmosphere from permafrost melt and from ocean plate rates, which are, icy substances on the seabed which contain a lot of methane. If the sea warms up enough and if the permafrost areas warm up enough, one of the dangers is you might get a huge surge of methane into the atmosphere, which would suddenly accelerate global warming by maybe 10 degrees very quickly.

Now, we know that could happen. We don’t know if it will happen. We don’t know whether there’ll be a big volcanic eruption. Most of you may not know, but volcanoes play a very big role in climate change. And we have been lucky enough, even me, and I’m getting pretty old and lucky enough to live through a time when volcanic eruptions have been relatively few and relatively small, and therefore, the climate has been relatively stable. But if a big one goes off somewhere, somewhen, that could easily precipitate a global winter lasting several years, possibly. And we’re not prepared for that. So we don’t know.