Wang Huiyao in Dialogue with Stephen Roach

The Center for China and Globalization (CCG) hosted Stephen Roach for a public event on the afternoon of Friday, May 31, where he gave a presentation on “Global Economic Outlook: Implications for China,” engaged in a conversation with Henry Huiyao Wang, Founder and President of CCG, and answered questions from journalists in the audience.

Stephen Roach is a Senior Research Scholar of the Paul Tsai China Center at Yale Law School. He joined the Yale faculty in 2010 after 30 years at Morgan Stanley, mainly as the firm’s chief economist heading up a highly regarded global team followed by several years as the Hong Kong-based Chairman of Morgan Stanley Asia. His latest book is Accidental Conflict: America, China, and the Clash of False Narratives.

The following transcript is based on a video recording of Roach’s presentation and his dialogue with Wang Huiyao at CCG and has not been reviewed by them.

Stephen Roach’s speech

Thank you, Henry, for your kind remarks. It’s a pleasure to be back here in front of CCG and try to stimulate some thinking on China and its role in the world economy. The conventional wisdom is that China is the world’s most powerful engine of economic growth. I think that has been true for a number of years. But I think we need to rethink that dynamic between China and the world, and the world and China.

My thesis that I want to just lay out for you today, with the support of a few slides that I brought with me, is that the engine, the Chinese global growth engine, is not as powerful as it used to be. There are some new sources of global growth that are evident, but even they are not enough to give the world the same type of support that we have become accustomed to. And the U.S.-China conflict, which is an ongoing subject of my own writing and research, represents probably the single greatest threat to the overall global growth dynamic in the years ahead.

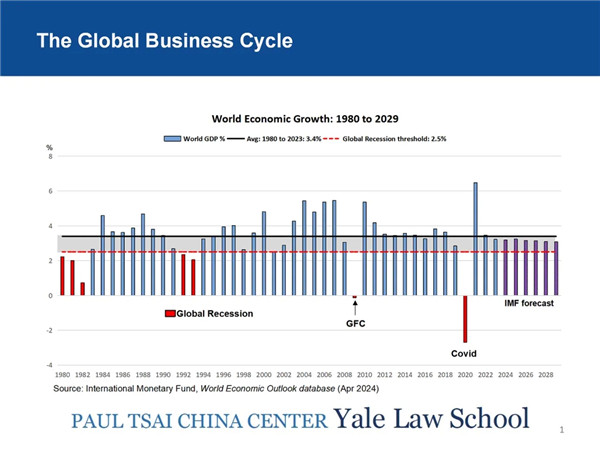

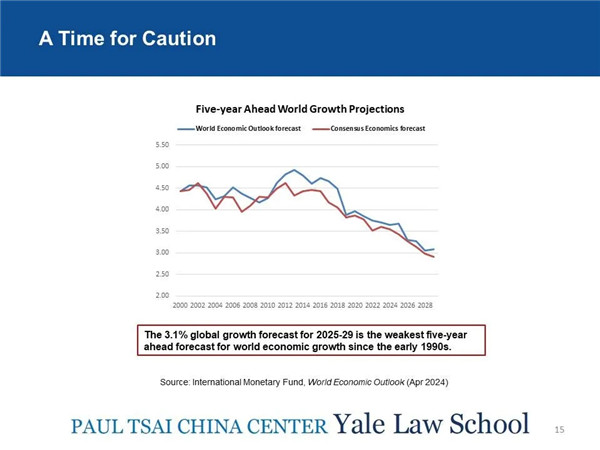

This is a busy slide, but it shows you a couple of things. 1, the IMF’s latest projections of global growth through the year 2029. And 2, a couple of horizontal lines, one drawn at 3.5%—the black line on the top, which represents the trend rate of growth in the world economy since 1960. Then the red line at 2.5%, below which the world is normally considered to be in a global recession.

The forecast looks okay between now and 2029, but it’s most importantly below trend. And when the world is growing below trend, it lacks the cushion that is normally required to deal with shocks, should they occur. That leaves the world vulnerable to the onset of a new recession.

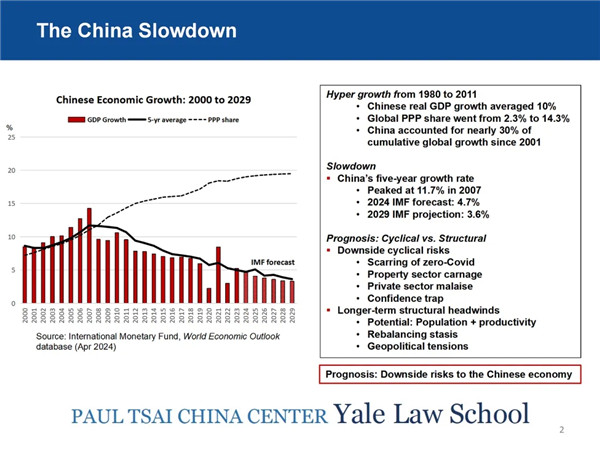

The China outlook is a very different outlook than we are accustomed to in examining your long, dynamic, and major source of global growth. On the left, the solid black line is the five-year trend in Chinese GDP growth, and it’s moving steadily lower and projected to do so between now and 2029. The peak five-year growth rate was 11.7% in the year 2007, and by the end of the forecast period, that number is projected to be 3.8%. That is a dramatic slowdown by any account that you can think of.

The slowdown can be broken down into short-term or cyclical pressure such as the property crisis or longer-term structural issues that I will talk about shortly that have to do with demography, total factor productivity (TFP), and geostrategic conflict with the United States.

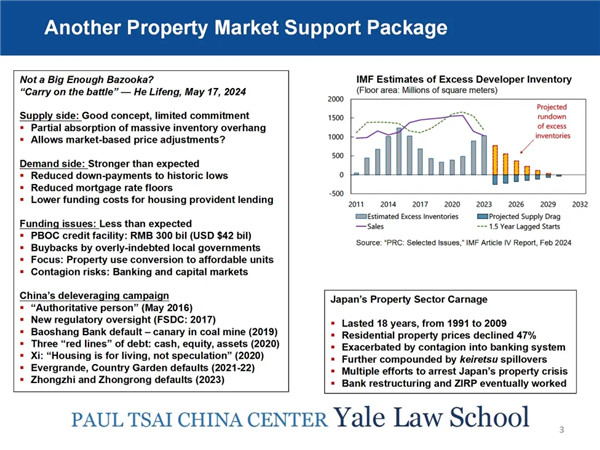

The property problem is China’s major cyclical growth impediment, in my view. The government has just announced a new property support package. In my humble opinion, it’s a step in the right direction, but it is not nearly large enough to absorb the excess inventory on the supply side of your housing market. The lending support package of the PBOC is inadequate to take up the outsized inventory of housing stock that is now overhanging the supply side of the Chinese property market.

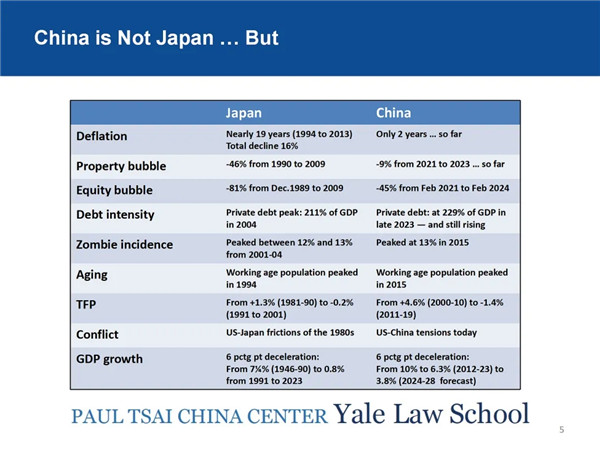

At Yale, I’ve taught two courses over the years that bear on this issue. One is a big class on the Chinese economy, and a second seminar is on the lessons of Japan. If you study the lessons of Japan carefully, you will know that the property crisis which lasted for eighteen and a half years in Japan, was a major impediment to the recovery of the Japanese economy in the aftermath of the “lost decades” of the 1990s and early 2000s. By many measures, the property problems in China are every bit as large as those which we saw in Japan. And we are only in the very early stages of addressing that problem. It took 19 years to address the Japanese property problems.

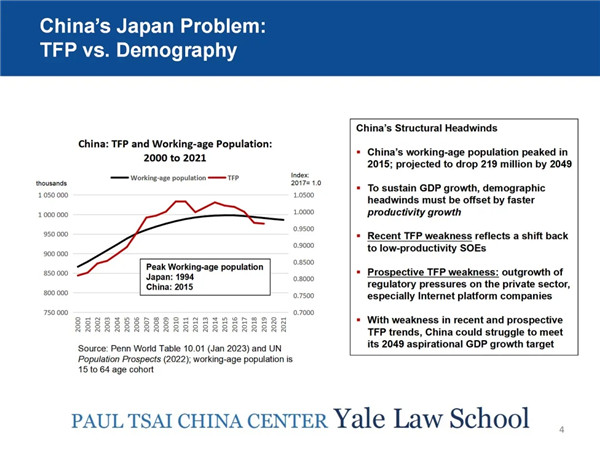

The structural issues in China are also surprisingly quite Japanese-like. I show you two major structural issues that are now afflicting the Chinese economy, the aging of the working-age population—of course, peaked in the year 2015—and the recent decline in total factor productivity.

In my lectures on Japan, I have the same confluence of structural problems that I can show you, but I’m not gonna show them to you today in the interest of time. I want to assure you the chart looks identical. The only difference is it took place 20 years earlier in Japan.

The way we do economics from a growth accounting point of view is when a nation is faced with a demographic problem of an aging population, the only way you can maintain rapid economic growth is to offset the demographic headwinds through increased productivity growth. Japan was unable to do that, and I worry about China’s capacity to do that as well.

TFP, as you see, has been declining actually since the year 2011, in large part reflecting the fact that much of Chinese economic activity is now taking place in low-productivity SOEs. The private sector, which has historically been a strong source of productivity growth in China, is now feeling the pressures of regulatory restraints, especially in the internet platform area.

So these two conditions make China sort of a worrisome parallel of what we saw in Japan, where the headwinds from an aging population will not be offset by an increase in productivity of those that are still on the job.

There’s a long chart here. I’m not saying that China is the next Japan, but there are clearly some worries and parallels as seen from the standpoint of asset bubbles, debt intensity, the incidents of corporate zombies, the aging demography, and of course, conflict with the U.S. Japan was in conflict with the U.S. on trade policy in the late 80s, and now it’s China. The U.S. always needs to blame somebody for its growth problems, and we like blaming large Asian nations.

One other thing about the Japan comparison that I will leave you with and then move on to the topic at hand, the global growth dynamic, is the notion of the Chinese growth shock itself. On the surface, it doesn’t seem to be a big deal. I mean, you can see what happened in Japan. (For) 45 years, the green bar on the left of 7.15% growth followed by 45 years of less than 1% growth. China has slowed, but in no way is that slowing as severe as that which has been evident in Japan.

But it is all relative. What you see on the right is the difference between the growth comparisons in the high growth period, Japan and China, versus that which has occurred recently in Japan and that which is projected to occur over the next five years in China.

If you take that IMF forecast as an accurate projection of what is to come—and you can argue against that—the deceleration of Chinese economic growth plotted on the right is almost identical to that which has happened in Japan since 1991. That’s a growth shock, whether you want to admit it or not. And when there’s a growth shock, that sort of changes everything. The idea that you can count on—rapid growth as the rising tide that masks all underlying problems—gets drawn into serious questions. If the IMF forecast is correct on looking at over the next five years of China, maybe you’re more optimistic than that, so it’s less of a concern, but I’m not. Then, the possibility of a Chinese growth shock being comparable to that experienced in Japan is something you need to take very seriously.

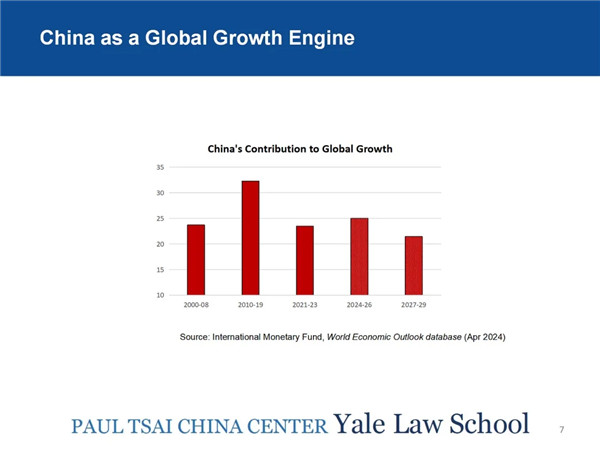

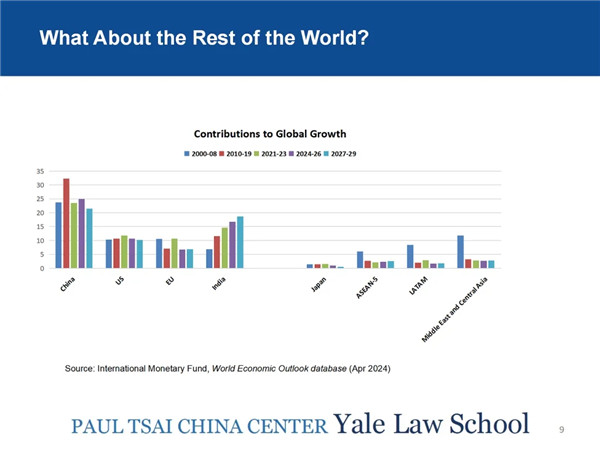

What does all that mean to world economic growth? This graph measures the cumulative contribution of China to global growth. You can see something very interesting about this. The second bar from the left shows the Chinese growth contribution added to maximum, close to 33% from 2010 to 2019. Then came covid. And post covid, the Chinese contribution to global growth has slowed dramatically. The 32% went down to about 24%. And again, on the basis of the IMF’s forecast, it’s gonna drop further to about 21% over the three years from 2027 to 2029.

So, China is still the most powerful engine in the world, but the power of the engine is diminishing. The idea that, we’re talking about China as being in and of itself enough to account for over 30% of global growth, needs to be rethought.

Who’s filling the void? Well, India is trying. If you look around the world for new sources of global growth, you can see that the Indian source, which was one-third of that of China’s in the 2010-2019 interval when China’s impetus to global growth was at its maximum, that Indian source is almost doubling by 2027-2029 when the Chinese growth contribution is slowing. I’m optimistic on India. Historically, I’ve not been as optimistic on India as I have been on China. But there’s a lot of attention being given to India right now as a new source of global growth, and it’s something we need to look at very carefully in the years ahead.

The rest of the world, I’m afraid to say, doesn’t really matter. I mean, you look at the U.S. share. It’s been roughly stable around accounting for 10% of global growth for a long period of time. I’m sorry, I know we have an ambassador here from Europe, but Europe is even less consequential in making a contribution to global growth than the United States. And then, if you look elsewhere in the world, Japan, ASEAN, Latin America, and the Middle East, they barely show up on the chart. So if you’re looking at the global growth dynamic, recently, currently, and respectively, China, the U.S., and India, those are the three sources that will matter the most. And I stress here this afternoon that the Chinese growth engine is not going to be what it used to be.

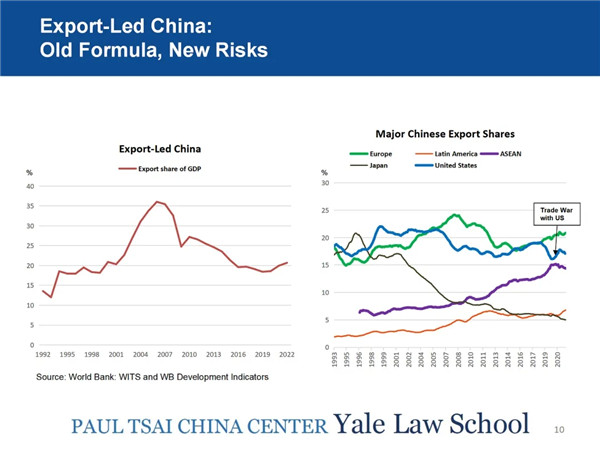

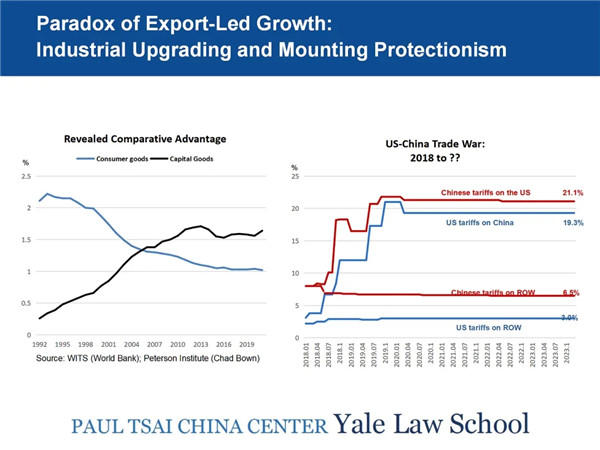

The final thing I want to talk to you about is the impact of conflict, especially the U.S.-China conflict, on the global growth dynamic. This is a worrisome development and potentially a big deal. For the Chinese economy itself, the export share of the Chinese economy has come down dramatically from its peak in 2007, but it’s on the rise recently. Xi Jinping in his latest policy pronouncements, is placing major emphasis on manufacturing-led and export-led growth in China, especially in the advanced technology and in the capital goods areas.

The U.S., at the same time, has resisted Chinese export growth. Thanks to former President Trump, who, as you know, was convicted of 34 felony charges today in New York, we are in the midst of a major trade war with China that was sparked by President Trump but continued under the Biden administration. These are U.S. tariffs on Chinese products, which were virtually nothing, and they’re still holding at about 19.3% of overall imports from China. Today, China, of course, has reciprocated, and that has had a significant impact on Chinese demand for U.S.-made goods.

The Biden administration has, as I said, continued to prosecute Donald Trump’s trade war. And I find this, you know, I’m trying to be fair. I’m not being either supportive of a Republican or a Democrat; I’m critical of both. When President Biden took office on January 20th, 2021, he signed 17 executive orders that unwound some of the most unpopular acts of the Trump administration. The trade war, the border wall with Mexico, the travel ban on Muslims, the U.S. getting out of the Paris Agreement on climate change, The World Health Organization, he reversed all of that, but he did not unwind Trump’s tariffs.

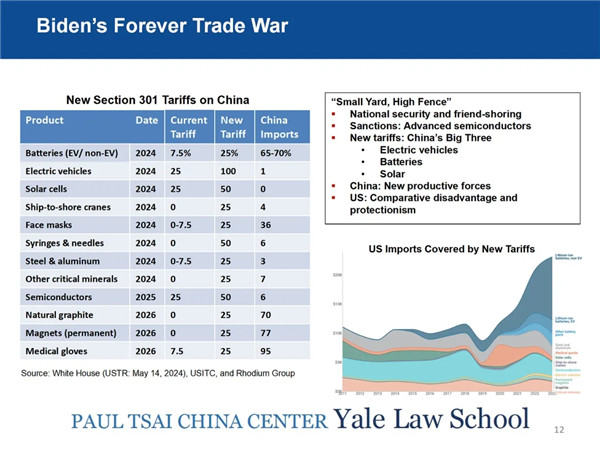

A few weeks ago, he announced a further expansion of tariffs under this provision of the U.S. Trade Act of 1974, known as Section 301. The most worrisome aspect of those tariffs, I think, was on these areas involving Chinese production of alternative energy products: batteries, electric vehicles, and solar cells. There are a number of other items that tariffs are increasing.

The points have been made: Don’t worry about electric vehicles, the tariffs are going to be 100%. But the U.S. doesn’t buy too many electric cars made in China, at least not yet.

I think there’s a huge strategic mistake driven by election-year politics in the United States. The world is in the grips of a horrific climate problem, desperately in need of new solutions through alternative non-carbon-fueled energy products. To take a protectionist stand against a country like China that has a comparative advantage in producing the non-carbon alternative energy products that a world in the grips of climate change desperately needs is a blunder potentially of historic proportions, in my view. It is precisely the wrong thing at the wrong time, in an example of how poisonous politics can be in shaping trade policy for the world’s leading nation.

President Biden has made a big deal about ending America’s, what he called, “forever wars.” That was the rationale that he used for getting out of Afghanistan in the summer of 2021. I worry that he is getting himself even deeper into a new forever war against Chinese trading practices.

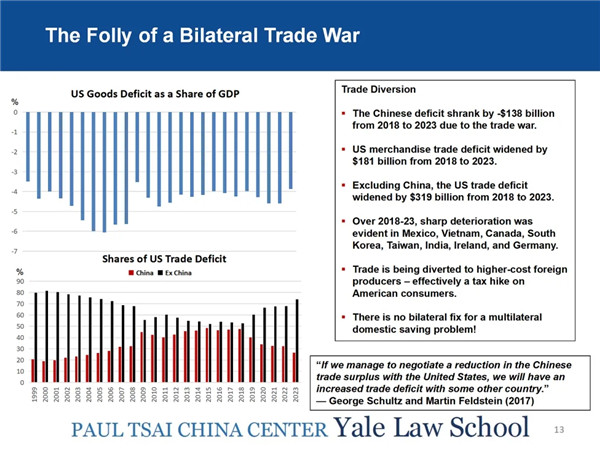

The U.S. continues to make the same mistake on trade policy today that it made with Japan, and that is putting pressure on one nation at a time when it really faces a trade balance that’s made up of many, many nations. We call it a multilateral trade balance. You can’t fix a multilateral problem by putting bilateral pressure on one of your trading partners. We have a multilateral trading problem because we have big budget deficits that depress our domestic saving. When economies don’t save and they wanna grow, they import surplus savings from abroad; they run massive current accounts and trade deficits with many, many nations to attract the foreign capital.

So, what has happened in the United States is that we’ve done to China what we did to Japan in the late 80s. We’ve reduced the Chinese share of our trade deficit, just like we reduced the Japanese share. The Chinese share of our trade deficits has gone down sharply from a peak of about 50% in 2015 to about 21% last year, but our budget deficits have gotten bigger, and our domestic saving has gotten lower. So the result is, all we’ve done is we’ve diverted trade away from China toward other nations that have picked up the slack, and those nations are listed right here: Mexico, Vietnam, Canada, South Korea, Taiwan, India, Ireland, and Germany. If you decompose their share of U.S. imports, 70% of that collection of nations are higher-cost producers than the U.S. So our trade policies are actually imposing the functional equivalent of tax hikes on American workers. Again, an example of the poisonous impact of politics on trade policy. We did it with Japan. We’re doing it again with China.

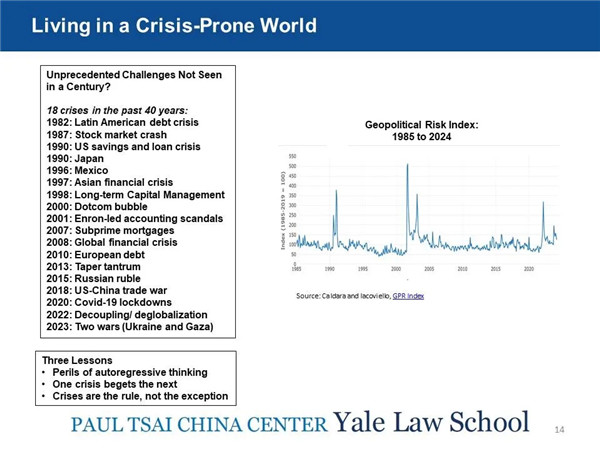

That gets me back to where I started with, and that is the global economic outlook. I showed you in that first slide, the global growth doesn’t really have the cushion that it would need to withstand the pressures of an unexpected shock.

What this slide shows you is that we’ve had a shock and the global economy—the list is too long to go through—but basically every two to three years. Given the mounting pressures on the U.S.-China trade front, you cannot rule out the possibility of another shock in the next one year or so. Markets are not priced for that. That’s what this chart on the right shows.

And the global economic outlook—this is a forward-looking forecast of world economic growth—is the weakest that it’s been since the early 1990s. So the possibility of an unpleasant surprise in global growth cannot be ruled out in light of this mounting conflict between the United States and China.

Henry mentioned the book I wrote a number of years ago. What he didn’t mention was a book I wrote last year that can be ordered on Amazon right now as you’re sitting there. It’s called Accidental Conflict. It focuses on the mounting risks of conflict between the United States and China, in light of the Trump tariff wars that have been prosecuted further by President Joe Biden, and makes the case that unless something major is done to bring our nations together—Henry mentioned my proposal for establishing a U.S.-China Secretariat, which I continue to be very much in favor of—that the possibilities of accidental conflict are something to be taken very seriously. With pressures building to this very day in the South China Sea, the Taiwan Strait, the new tariffs that President Biden is imposing on China, this is something to take very seriously and something that we must stand up and say no to today if we are serious about defending the strength and resilience of the global economy. Thank you very much.

Dialogue: Stephen Roach & Henry Huiyao Wang

Henry Huiyao Wang

Thank you, Stephen, for your excellent presentation. I think it’s really helpful for all of us to have a better understanding of what’s going on. You outlined the global growth, what China’s contribution can be and continue to be, and the challenges and opportunities. Also, you talked about the experience of other nations like Japan and India. Then you talked about the problems that we’re having now. This is a great overview.

Now, we will get into the dialogue section, and I would like to ask you some questions. Firstly, you mentioned this IMF forecast. I think that was very interesting because the IMF recently raised its 2024 and 2025 projected growth for China by 0.4 percentage points to 5% in 2024 and 4.5% in 2025. This is interesting, but you mentioned that the trend is coming down. The question I would like to ask is that China, with its magnitude, with the size of its economy, is the second largest economy. Given the high base, today, even 5% or 4.5% growth is probably equal to 10% ten years ago or 15% twenty years ago. Every year, there’s a large GDP equivalent of—I don’t know, Australia or Indonesia—added to China.

The other thing is China is transitioning from high-speed growth to high-quality growth. For example, I remember that many years ago, people were talking about 700 million shirts exchanged for one Boeing 747. Now China has become the largest exporter in the world. So there’s a lot of quality changes. How do you interpret that? Even though the speed may come down, the quality may pick up, which is needed. How can we really continue that kind of transition from high-speed to high-quality growth, and what are the things we still need to be cautious of, and how can we continue that positive momentum, even though we’re not achieving the high speed we used to have?

Stephen Roach

Well, you touched on a few things, Henry. One, the IMF’s forecast revision (by) half a (percentage) point. In the way that forecasting accuracy goes these days, it’s an upward revision, but it doesn’t change the basic story of an economy that is still growing at best about half the pace that it did in the high-growth era when the Chinese economy grew 10% for 31 years from 1980 to 2011.

You’re right that as the base gets bigger, smaller increments mean more. But my point on the growth shock that I tried to end with is that this has been abrupt. The slowdown has been concentrated in the last few years. When China was growing rapidly for much longer than anybody thought, the expectations were built in that China and the world could count on rapid growth, irrespective of the base effects going forward. This notion that the leadership continues to boast about in addressing global forums, like the China Development Forum—and I heard Premier Li say this at the China Development Forum at the end of March, that China accounts for, I think the number he used was 35% of global growth—that’s out of date. That number is no longer accurate and it’s going to get smaller.

Your final point though is, I think, the most important, that is, moving away from a focus on the quantity to the quality of growth. I’ve had the privilege and the opportunity of making speeches in this country every year in the last quarter of a century. I’ve always pounded the table on precisely that, shifting from a fixation on quantity to improving the quality of economic growth. How do we measure the quality of economic growth? You can measure it through environmental metrics. I was delighted to wake up this morning, drive across town, and see a beautiful blue sky in Beijing. I think there has been some improvement in air quality in China over the last, I don’t know, ten years.

My favorite scientific metric for quality though, is total factor productivity (TFP). The trend there is worrisome. From the 2011-2019 ten-year period, TFP growth, as we call it, has been dropping by a little over 1% a year. And that follows a big upsurge in the prior 15 years. That is a worrisome sign of the deteriorating quality of Chinese economic growth because it raises questions about the efficiency of labor and capital in generating sustained growth in overall economic output. You cannot have high-quality growth with weak TFP.

The final metric to think about, and it gets a lot of discussion in China, is the measures of the equality or inequality of the income distribution. The conclusion is pretty straightforward based on most metrics that China—and China is not alone in this respect—certainly has problems with mounting income inequality as well.

Henry Huiyao Wang

Thank you, Steve. Excellent point. Absolutely, we need to address all those inequalities. The better life of its people is really the target the Chinese government is striving for. While maintaining high quality, we have to maintain equality. So that’s really a good point.

But I’d like to also touch upon the other issue that you raised. You talked about Japan. You talked about the aging population and whether China is going to repeat what Japan has gone through. What is the impetus, and what is the next drive for the Chinese economy? The real estate market, as you mentioned, is slowing down. What is the next, the biggest, transformative policy that the government can propose?

Here I’d like to discuss a bit of our thinking with you. For example, the third plenum of the 20th Party Congress is gonna happen in July. We’re expecting a lot of new policies. Talking about real estate, Premier Li mentioned at the China Development Forum in March this year that the urbanization of 300 million migrant workers would probably be the next drive. So I’m thinking about how we can transform that into a concrete policy in addition to trade-in and other policies.

In the last 45 years of China’s opening up, every ten years, there’s always a revolutionary policy driving up the process. For example, in the 80s, the government had a policy of contracting the land for the farmers to grow whatever they liked, a breakaway from a planned economy. Then Chinese society changed from a society of shortage to a society of abundance. So that policy has changed China dramatically.

Then in the second decade, the government realized that the real estate market in the cities could be allocated to workers and other urban residents in the city, privatizing the flats at a minimum cost. So everybody in the city had or bought an apartment, which cultivated a 400 million middle class.

Then in the early 2000s, China joined WTO, which was another revolutionary policy. Before that, only a handful of SOEs were allowed to conduct foreign trade, and now 6 million companies can do that. China became the largest trading nation in the world.

So for the last ten to fifteen years, where is the long-hanging fruit, the revolutionary policy that we can tap into? Premier Li’s comment at the China Development Forum stimulated me to think. As you also mentioned in your presentation, Japan, the U.S., and other Western countries have an urbanization rate of 80%, whereas China only has 66% according to Premier Li. Yet only 50% of urban dwellers in China have the hukou and city resident benefits. The other 16% do not have them. So we are talking about 300 million migrant workers living in the city but not enjoying urban rights.

The reason for that is they have household land in the rural area. The rural area household land is empty with only seniors and youngsters, but also they are renting a lot of apartments in the city. So there’s a lot of redundancy and waste.

I’m thinking, like in the 90s departments were privatized for the workers, can we allow the farmers who have already settled in the city to sell their household land in the rural area, so that they can get their startup capital to afford the downpayment for secondhand real estate in the cities? This could prevent these 9 billion people from traveling around during the Chinese New Year and contribute to social justice. Would that be the long-hanging fruit that we can hope for? I would like to hear your comments on that. Thank you, Steve.

Stephen Roach

I think it’s a great idea, Henry. I like your thinking. I would like to broaden it out, though, because you introduced this by saying every 10 to 15 years, there’s a big change that injects new energy, a new source of growth into China. I have been pounding the table for longer than I can remember about the need for a new impetus to household sector private consumption in China. The numbers are very clear. The latest share of Chinese GDP going to private household consumption is below 38%. 38%! That’s ridiculously low.

Now, your proposal goes right to one aspect of that, and that is to the 300 million migrant workers who clearly have the potential to be tapped as a new source of consumption. I would say that that is necessary but not sufficient. So I’m endorsing you. But I would say, of equal significance would be the need to inject much more funding and vitality into the social safety net—healthcare and retirement, because I think that is the biggest impediment to discretionary consumption because it keeps families who are aging rapidly predisposed toward precautionary saving in providing for the future. And to the extent that a nonsignificant portion of those families lack hukous because of their residency preference, that would be additive to that problem.

So I would combine the two into a much broader program, aimed at injecting new stimulus into private household consumption in China. I think it’s a good idea, but it’s not enough in its own.

Just say one other thing about the current Chinese policy strategy. Like you, I was also at the China Development Forum and heard Premier Li address policy priorities for China. He repeated a theme that he had emphasized in his work report a month earlier to the National People’s Congress, saying that the real priority, the most important priority is focusing on new productive forces aimed at boosting manufacturing and in particular, a new round of export-led growth in China. He mentioned, in addition to that, the need to stimulate domestic demand along the lines of what you and I have been talking about.

The first priority, though, is one that is clearly causing a lot of negative reaction in the U.S., increasingly in the G7, and it’s all wrapped up in this excess capacity debate that I alluded to in my own comment. This twofold strategy is important for China, but it creates conflicts that I think are also problematic in shaping the growth outlook in this country.

Henry Huiyao Wang

Great. Thank you, Stephen. Absolutely, I agree. You mentioned that we should really have a new, strong impetus or stimulus or revolutionary policy that is badly needed, not only by China but also by the world. I think real estate is one of the biggest factors because in the Chinese traditional thinking, if you have a piece of asset, then you are confident, you are gonna spend more, you are not gonna take the wallet close to your chest and then withhold from spending. So I think stabilizing the real estate market is crucial. Actually, I’ve read somewhere that there are apartments built in China enough to house 200 million people. If we move all the 300 million migrant workers to the cities and let them have a legitimate identity to live in the cities, they’re going to contribute to the stability of China.

Now I’d like to ask another question. You mentioned just now new quality productive forces. Interestingly, you also mentioned the tension on those tariffs President Biden raised on the EV cars, batteries, solar… all those new green energy technologies and products. Actually, according to the International Energy Agency, in order to combat climate change, according to the Paris Accord, we probably need at least 800 gigawatts of new green power to combat. Now we can only produce a quarter of that. The world needs to spend 4.5 trillion U.S. dollars per year on green spending. The world is only spending 1.8 trillion U.S. dollars, which is far from oversupply. I even read that the European government is considering extending their phase-out of the diesel and gasoline-driven cars, originally set in 2035, now extending to 2040, because they want to extend the life of diesel and gasoline cars.

So if we are having so bad a climate change, it’s really strange to see that given the U.S. and even sometimes Western countries are calling for more products, and more technology available to combat climate change, now China has developed that, they’re refusing to have it, even putting tariffs on it. 90% of the commercial flights are supplied by Boeing and Airbus, yet we don’t see it as overcapacity.

I just want to get your opinion as non-Chinese. What do you think about it? We urgently need green products in this world, and China, after so many years of experiment, hard work, and trial, with the opening up and help of every country, has this product available. However, now some countries are saying, “No, they’re over capacity.” So what do you think? What’s your take on this question?

Stephen Roach

I think it borders on insanity. In a world that is facing unmistakable signs of climate change, there is no such thing as “excess capacity” in non-carbon green energy products. If anything, there’s a shortage of alternative energy products.

China is providing an enormous service and a benefit to the world in producing low-cost clean energy products that the world desperately needs to protect itself against the ravages of climate change. China has the technology, the scale, and therefore, by definition, the comparative advantage in delivering exactly what a climate-torn world needs.

We resist this purely for political pressures because we have this desire led by the United States to contain Chinese economic growth and development. We also have, as you have in China, national security concerns. I can think of no greater threat to national security than destabilizing the world’s climate. So if we’re serious about looking at national security or from the standpoint of the security of our planet, we need to be, I think, much more appreciative of the need to allow the nations that have a comparative advantage in giving the world what it needs support rather than resistance.

Henry Huiyao Wang

Thank you for your very good views that look at this issue. I appreciate that. Absolutely, the world is really burning. We really need to work together.

Also, you mentioned the book you have. This would be my last question before I open up, but I’d like to ask you this question before I do so. You mentioned about the book Accidental Conflict, Accidental Conflict: America, China, and the Clash of False Narratives, which is exactly right because you gave me that book last year. I read it. I found it very fascinating.

You know, the perceptions and narratives of both countries, China and the U.S., are totally different. So how can we really get more right narratives? You talked about, for example, national security. There’s too much emphasis on national security now that’s driving up all those things. But equally important, even more important, climate security, food security, energy security, environment security, and…

Stephen Roach

Health security.

Henry Huiyao Wang

Health security, absolutely. Human security. We recently had just had a big symposium in Washington to talk about human security. I think those are really important. So how can we really gradually have the right narrative and global governance for those common concerns rather than developing into two camps?

There’s more security alliance built up, but on the other hand, China’s doing a lot of economic alliance for globalization. How can we really converge that? China and the U.S. have more responsibility for the human security. I’d like the idea of a Secretariat for the China-U.S. relations.

Stephen Roach

Well, let me just give you my theory behind your important question, Henry. When I started working on this book four or five years ago, I started out with some of the ideas that I summarized on the slides today. And that is that we have in the United States many false impressions about China. Then as I did the research, I said, wait a second, there’s a number of false impressions that China has about the United States as well. And the reason that both nations have false impressions or false narratives about each other, and they have such important impacts on the policy actions that we take toward one another is because of politics. We let political pressures drive wrong-directional policies, in my view. That’s true of trade policy in the U.S. and it’s true of China’s concerns about America as a threat to its national sovereignty.

So what I end the book on is recognizing that the politically-driven process of engagement that both nations have embraced since the early 1970s is more driven by politicians than by technocrats. Politicians tend to operate on the basis of appealing to workers or promising they are citizens of a better life. They get us into trouble.

So my proposal is for a new organization that I call a U.S.-China Secretariat that really changes the architecture of engagement between the two superpowers, takes it out of the hands of the politicians and the leaders who are driven by their own personal political agendas—with all due respect, you have the same problem that we do—and puts it in the hands of technocrats who have a broad remit to deal with all aspects of the relationship, not just when the leaders meet once a year, but 24 hours a day, seven days a week. They deal with trade, economics, innovation policy, technology transfer, industrial policies, subsidies, sustainable enterprises, the big existential issues like health, cyber, and climate.

It’s an organization that is built around a collaborative model of research based on a common, mutually agreed upon database. It’s an organization that collectively works on the oversight and compliance of existing bilateral agreements. Should disputes arise, it screens disputes and has a built-in dispute resolution mechanism. We need a new architecture of engagement. The current structure is creating conflict as opposed to conflict resolution. If we don’t get serious about addressing our mutual issues, we will not have conflict resolution, we’ll continue to have conflict escalation, and that is the biggest risk of accidental conflict. We have got to change it.

Henry Huiyao Wang

Thank you, Steve. That’s absolutely crucial. I’m all for this proposal. China and the U.S. should really have a close working team. Also, you mentioned the policy on both sides. Absolutely. We see that globalization is affecting many working class, while Wall Street is hitting an all-time high. The 1% of Wall Street is equal to 40, 50% of the mass population in the U.S. And then the gap is really big. There’s a lot of social injustice, but then we cannot have that all blamed on China because, you know, the business is making all the…

Stephen Roach

Politicians need someone to blame. That’s why, again, I am not in favor of a political solution to the type of superpower conflict that we have.

Henry Huiyao Wang

Absolutely. So I think on that note, we’ll finish our dialogue. I totally agree we should increase dialogues and mutual exchanges, and create a new narrative.

China and the U.S. have a huge responsibility for human security and for the future to come.

Now I’ll be open up for the questions. I know the China Daily is here, is that right? We also have Beijing Daily, China Internet Information Center, and the Global People Magazine. Does anybody want to start? We have three in a row. Okay, from the back row.

Q&A: Stephen Roach & live audience

Eason Zhen, Reporter from Global People

My name is Eason Zhen. I’m a reporter from the Global People Magazine. I hope to thank CCG for organizing this event. I have two questions if it’s okay.

My first question is that we actually had an interview with Professor Roach about 11 years ago. Back then, Professor Roach said he was a long-term optimist of the Chinese economy. So I’m wondering right now, do you still believe this?

My second question is about Sino-American relations. Professor Roach and Mr. Wang discussed certain false impressions China and the U.S. have on each other, but what we see is when facing economic difficulties, China has a greater consensus that cooperation with the U.S. will be a solution to the economic stagnation, while the U.S. politicians tend to believe the relationship with China is a threat to their economic development. So I think this is a great difference.

In this situation, from your both perspectives, do you think the current trade disputes between China and the U.S. demonstrate a long-term trend in the U.S. foreign policy toward China or is it more like a short-term policy? Is it just a symptom that the U.S. politicians are trying to adjust to the new reality of the bilateral relationship between China and the U.S.? Thank you.

Stephen Roach

Those are good questions. I will deal, first of all, with my own view. If I met you 11 years ago and I said I was optimistic over the long term, 11 years is a long term. So, you know, I stayed optimistic probably for 10 of those 11 years. That’s a long time, right?

More seriously, my outlook is certainly more cautious today than it was back then, and in fact, more cautious right now with respect to China going forward than it has been at any point in the 25 years when I was actively involved in following China’s economy, both living here and from abroad.

I changed my view in the last year or so in large part for the reasons I mentioned in my presentation. The demographic changes are happening much more quickly than we thought. The UN demographic projections as recently as two to three years ago called for the Chinese population to peak in 2031. It happened in 2021, ten years earlier.

And number two, the TFP issue, total factor productivity. The trends have been weak. There are now growths of conscious policy choices that the Chinese government has made not only to throw more support behind low-productivity SOEs but to put tighter regulations on higher-productivity private sector, especially internet platform companies.

The third and final consideration in my shift has to do with my deep-rooted concerns about the U.S.-China conflict, which has really gone from bad to worse over the last few years, which gets me to your second question on the conflict itself. There are different perceptions on both sides of the relationship about the role that each nation can play in supporting or in constraining each other’s prosperity.

You’re entirely correct. The Washington view is that China is a threat to long-term prosperity. China has not had that view about the United States until, I would say, the last year. It was a year ago at the National People’s Congress in early 2023 when President Xi underscored for the first time concern that U.S.’s China policies were now posing the long-term threat of suppression, all-around containment of China’s growth and development objectives. And this represents a shift in his point of view as well.

Both of these perceptions come from different places, but they end with the same emphasis on mutually shared perceptions of conflict, which I think are worrisome for the long-term stability of our economic and political relationships.

There’s still, I think, good spirit on a people-to-people basis. But even that, over time, I think, becomes adversely affected if the economic, political, trade, and technology conflict continues to deepen.

Henry Huiyao Wang

I feel that the Chinese economy, as you mentioned, faces the aging population, demographic changes, and all those things. But on the other hand, you know, there’s more synergy now. You have the best infrastructure in the world. You have 70% of the 5G networks. You have 12 million freshly-graduated, single-child, well-educated talent pool. And of course, you have 1.1 billion smartphone users. So there’s a lot of productivity. For example, China has already become a cashless society and productivity is at an all-time high, probably in terms of certain areas. So I’m not that pessimistic, but I think, you know, things could change.

As for China-U.S. relations, of course, President Xi also mentioned you have 1,000 reasons to be in good relations, not a single reason to be in bad relations. I think China was responding more to the U.S. hostile policy, but still, we want to maintain good relations. President Xi even invited 50,000 American young people to come to China. So let’s hope for the best.

The gentleman from Bloomberg, I suppose?

James Mayger, Senior Reporter, Bloomberg News

I have a question about overcapacity, but I want to sort of step away from the “three new” or the new energy products you’re talking about and look more broadly at the economy. If you look at steel production or if you look at all the things that go into housing, production is still at the same level as it was before the three red lines policy was brought in. We’re looking at a billion tons of steel being produced this year, but demand for that domestically is nowhere near where it was. So that’s being exported. Much steel exports wrote a record. You’re seeing petrochemical exports for plastics and also things that can’t be used in housing anymore in China are being exported.

But if you think about the green transition and decarbonization, steel production is a big driver of carbon emissions. So it would seem that China is exporting these products because it has continued to produce domestically, even though there really isn’t a need for it to even be making these products in the first place. And then making those products leads to greater carbon emissions.

So sort of thinking about the overcapacity question more broadly than just batteries and EVs and solar panels, do you think that there needs to be more done in China to deal with the capacity issues that are being seen in the industrial economy?

My second question is on the tariffs that the U.S. has put in place specifically. The argument of the USTR and the government is that they’re providing space for domestic industry and for foreign investment to build those same sectors in the U.S. that China built over the last 10 years in China. Their argument is that this will lead to the production of these products in the U.S., which will eventually drive down the prices because it will lead to a competitive industry in the U.S. and also in China. Do you not think that is a useful policy choice that they’re trying to make? And over the long term, do you think that will lead to cheaper prices for these goods globally? Thank you.

Stephen Roach

Well, you know, I think that there are certain areas—and you point to steel—where there is a supply-demand imbalance domestically that is being reflected in sending that supply out into foreign markets. I would argue that it is a symptom of a bigger problem in China, and that is letting too much of the industrial sector, now being supported and driven by State-Owned Enterprises that are less susceptible to market pressures, that might otherwise promote a more rational balance between supply and demand.

I think the emphasis on SOE-led industrial activity does create inefficiencies with important global repercussions. And that just underscores the need for intensified efforts at SOE reforms that over time, I think would begin to alleviate that type of problem.

The rationale that you described for putting up barriers to protect nascent green energy production in the developed world, I reject that completely. If anything, it will make the competitive pressures less intense as protectionism always does. I think the cost differential between the U.S.-China and EU-China on EV batteries, even solar panels is so wide that protectionism—all that will do, I think—will again keep the global price level higher than one otherwise be the case. So I think this is a tax on precisely the types of products that a world afflicted with climate change needs more than ever. And I would not be in favor of or support that type of rationale, to just “give us time to catch up.”

Henry Huiyao Wang

Thank you. Okay, we’ll have the lady in the front row.

Reporter, China Internet Information Center

Thank you for the opportunity. I’m a journalist from the China Internet Information Center. The first question, you have just stressed the importance of total factor productivity. You said that China cannot achieve high-quality growth with a weak total factor productivity. So what are the suggestions for the Chinese government to improve total factor productivity?

And the second question, how would you evaluate the trade relation between China and the U.S.? How would you evaluate the impact of the U.S. election on China-U.S. trade relations? Thank you.

Stephen Roach

TFP policies, again, there’s a long debate of this in the economic and policy literature. Investing in human capital, innovation (is) all part of the agenda. These are areas where I think China is in very good shape to boost TFP.

My theme that I have underscored several times today is to shift the mix of economic support away from low-productivity SOEs to higher-productivity private sector, especially technology companies. Without doing that, many of the other things that are being achieved so successfully in China will just get lost in the equation. That would be my single most important objective.

In terms of the election, what we’ve seen from President Biden, as I indicated in my presentation, has been a surprising and disappointing continuation of the protectionist approach that was sparked by President Trump. And I don’t see any signs that President Biden is going to rethink this approach should he be reelected at the end of this year. And former President Trump, who, the last I checked, is still running even though he might be behind bars in November, is in favor of massive further increases of tariffs on Chinese products. So I don’t think we can count on him for delivering spontaneous relief on the U.S.-China trade front either.

Henry Huiyao Wang

Okay, good. Maybe last round, I don’t know if China Daily or Beijing Daily was here.

Reporter, China Daily

Thank you. I’m a business reporter from China Daily. I’ve got two questions.

My first question is, China has made progress in containing the risk of a debt deflation loop and increasing efforts to support housing inventory digestion, how do you see those moves to stabilize the economy, and what efforts are needed to do more to boost China’s economic recovery or tackle some structural issues?

My second question is, actually recently China’s top leadership has addressed the importance of deepening economic structural reforms. The third plenum will be held in July with a key focus on reforms. So what will be the key policy focus for China to deepen economic reforms? Thank you.

Stephen Roach

The recent initiatives, I think, are steps in the right direction, but only steps. The property sector package has the right focus aimed at absorbing the inventory overhang of unsold housing units. However, the funding support as announced by the People’s Bank of China is too small.

If there’s a lesson that we’ve learned from earlier housing property crises, whether the Japan or the United States, is you need what we call a big bazooka. That means a big gun, a large package. Err on the side of doing too much, not too little. This package is too little. It’s incremental. It absorbs only a small portion of the overhang. It’s going in the right direction, but it needs far more funding support to really make a major dent in the overhang of unsold housing units.

In terms of the upcoming third plenum, I think the government has been very explicit and emphasizing, whether it’s President Xi or Premier Li, the efforts on new productive forces, and new technologies. And President Xi in fact even indicated in a signed article late last year that his metric of success would be TFP. So that’s very clear. What’s not clear though is the second issue, one that Henry and I have both addressed, and that is to really deepen and expand the emphasis on supporting consumer-led rebalancing in China.

Henry has some proposals on hukou reform and transferring ownership of rural residences. That is very important and I support them. I have made recommendations for years on the social safety net, healthcare, and retirement. I think policies need to be formulated more explicitly and more comprehensively to address the shortfall of domestic household consumption in China. Without the Chinese consumer, I think economic growth is going to remain a big question mark in the years ahead. And the third plenum is the time to address that. And I would hope that more progress would be made in the upcoming reform agenda.

-Realted-