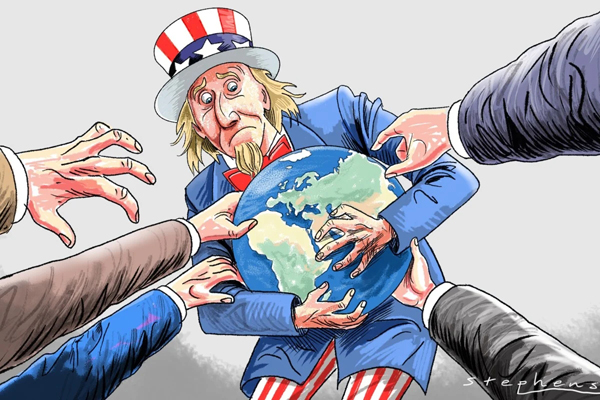

Zhou Xiaoming: Imagine a world free from the oppression of a US-led global order

March 28 , 2024■ It would spell the end of the US ability to impose its will on the international community, shape other countries in its image and shift the burden of its economic crisis onto others.

By Zhou Xiaoming, a senior research fellow at the Center for China and Globalization(CCG) and former deputy permanent representative of China’s Permanent Mission to the United Nations Office in Geneva.

A spectre is haunting Washington. It is what Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim recently described as “China-phobia”. Just as some neurotic people see ghosts in broad daylight, so American politicians watch China’s every move with suspicion and apprehension. They view Chinese products such as 5G equipment, port cranes and cars as Trojan horses, and are working hard towards a TikTok ban on national security grounds.

Beneath Washington’s fear lies the perception of China as a major adversary, which it believes is intent on destroying the “rules-based international order”. What would an upending of the system mean for Washington?

To start with, it may spell the end of US domination in global affairs. The so-called rules-based international order, invented and perpetuated by Washington and its Western allies, allows the US to impose its will on the international community.

If upturned, it would probably end the US ability to single-handedly block the decisions of international organisations, as it did with recent UN Security Council resolutions on the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, and the working of the World Trade Organization’s dispute settlement system, paralysed after the US obstructed the appointment of judges to the appellate body, reportedly for 60 consecutive times at WTO meetings.

Washington would also find it difficult to call the shots at the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. In these two institutions, votes on substantive issues need 85 per cent approval. The US, with its vote shares of over 15 per cent at the World Bank and 16.5 per cent at the IMF, has effective veto power.

World Bank presidents have traditionally been American. But if there is a major change in the institutional set-up, this position would more likely be occupied by an Asian, African or Latin American, chosen on ability rather than nationality.

Moreover, Washington’s ability to shape other countries in its own image would be severely eroded. Washington seems to be in the habit of meddling in the internal affairs of other countries through imposing sanctions and stirring up civil strife in the name of human rights and democracy, as in the case of Libya and Syria.

Washington attempted for decades to shape China. Nevertheless, as US national security adviser Jake Sullivan recently admitted, its efforts were to no avail. With Washington’s beloved international order gone, such “failures” would increasingly be the order of the day.

Additionally, Washington would have to give up its penchant for war – on the soil of other countries. As “the most warlike nation in the history of the world”, as former US president Jimmy Carter put it in 2019, the US had been at peace for only 16 of its 242 years as a nation.

The US would no longer be confident that waving a tiny bottle of powder at the UN Security Council convinced the world that invasion of another sovereign country is justified. Human right violations would become a detestable excuse to wage war against countries that Washington deems in the way of its geostrategic objectives.

The US would also lose its firm grip on the global financial system. Once the US dollar’s position as the world’s major reserve currency is battered, Washington would no longer be able to shift the burden of its economic crisis onto other countries, as it did in the 2008 financial crisis.

Neither could it hope to “fleece” other countries by varying its monetary policy. Moreover, it may struggle to cut other countries’ access to international payment systems, Swift (short for the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication) or otherwise.

Upturning the “rules-based international order” would mean the loss of American exceptionalism. In the US, federal law can take precedence over international laws and its courts have been known to have declined to apply international laws. Last year, a Chinese commerce ministry report found the US had the largest number of cases of non-compliance with WTO rulings.

In the event of a collapse of its beloved international order, the US would have to trash its everybody-but-me approach and observe international rules as other countries do. It may also be forced to respect the opinions of other nations so that every country is equal before the international law.

Obviously, such a transformation would be extremely painful for Washington. However, wouldn’t Washington’s loss be a gain for the developing world?

In essence, Washington’s rules-based international order equates to its global hegemonic position. It runs contrary to the fundamental interests of the Global South, who desire a fairer international order, not one designed to maintain the West’s entrenched privileges. This inevitably places Washington on a collision course with the developing world.

In contrast, China champions an international order based on international law. It pushes for a shared future for mankind, with no country left behind, and strives to build a multipolar world where every nation, big or small, has a say.

Importantly, Beijing has time and again stressed that it has no intention of replacing the US. Instead, it seeks peaceful coexistence, cooperation and mutual benefits. But China’s words seem lost on Washington.

Those educated with the “winner takes all” tenet believe, as US Secretary of State Antony Blinken does, that you either sit at the table or end up on the menu. The idea of everyone having a seat at the table is beyond their imagination.

But China’s aspirations for the future of the world appear to be in alignment with those of other developing countries, as evidenced by the increasing popularity and dynamism of Brics, a grouping backed by China.

From SCMP, 2024-3-28

Topical News See more