Mehri Madarshahi: World Order at the Breaking Point

February 04 , 2026

By Mehri Madarshahi, CCG nonresident senior fellow

World Order at the Breaking Point: Middle Powers Reshaping the Global Order

As global leaders gathered in Davos, the familiar language of cooperation and reform gave way to a more sober reckoning with fragmentation and power politics. Unlike previous editions that emphasized globalization, climate consensus, and technological optimism, this year’s agenda was shaped by geopolitical rivalry, economic constraint, and social polarization. Slowing growth, persistent inflation, and fiscal pressures narrowed policy space, while strategic competition increasingly governing trade, investment, and technology were on the main menue.

At the same time, rapid advances in artificial intelligence were no longer framed primarily as engines of shared prosperity, but as sources of disruption, inequality, and contested governance.In this climate of uncertainty, Davos no longer functioned as a forum for reaffirming global consensus, but as a barometer of a world struggling to manage discontent, complexity, and accelerated change, where clear thinking and decisive leadership were less aspirational ideals than systemic necessities.

The discussions in Davos revealed that multilateralism is faltering not because its institutional architecture has disappeared but rather for lack of credible leadership to animate and sustain it. The prominence of leadership and institutional fatigue at this year’s Davos thus signaled a deeper reckoning: the gap between the complexity of global challenges and the declining capacity of existing governance systems to address them.This was the story of the 56 World Economic Forum known as Davos 2026, which was held from 19-23 January in Switzerland.

In the past, the character of Davos meetings was shaped both by the issues they addressed and by those invited to define them. The usual three, largely complementary pillars periodically dealt with over the past few years comprised:

Confidence in globalization, Confidence in globalization was grounded in the assumption that deepening economic interdependence would continue to underpin stability and growth. While concerns about inequality and resilience were periodically acknowledged, globalization itself was rarely questioned as the organizing principle of the international economic system.

Climate alignment reflected a growing, if fragile, consensus around multilateral climate governance. Davos increasingly in the past functioned, as a platform for advancing net-zero commitments, green finance, and public-private partnerships, premised on the belief that environmental sustainability could be reconciled with economic growth. Climate action often was presented not as a zero-sum trade-off, but as a unifying agenda capable of mobilizing states, markets, and civil society around common goals.

Technology-driven progress often was articulated through an optimistic narrative of innovation. Digitalization, artificial intelligence, and automation were widely framed as engines of productivity, inclusion, and problem-solving. Governance challenges were acknowledged, but often treated as secondary to the transformative potential of technological advance.

These issues were to be debated in this year’s meeting, where a record level of heads of state or governments (from 65 coutries), 3,000 participants from over 130 countries and Nearly 850 CEOs and chairpersons from leading global companies were in attendance.

Throughout, the Forum was defined by contradiction, optimism tempered by uncertainty, big themes overshadowed by bigger personalities and AI’s momentum challenged by question of delivery. At the center of all was the return of Donald Trump. His midweek arrival dominated both the schedule and the mood, pooling focus from nearly every panel and private session, even before he spoke.

In a strong nationalist and economic message, he portrayed the United States as the engine of global economic strength, claiming significant U.S. growth and resilience under his leadership, contrasting it with what he described as weaker performance by European countries . He openly criticized Europe and NATO, suggesting Europe was “not heading in the right direction”. His remarks went beyond routine diplomatic criticism, adopting a more confrontational tone toward some traditional partners when he focused onGreenland. He said that “the U.S. wants to gain control of the island, since the United States is uniquely capable of defending it”.

Emphasizing U.S. industrial production and the energy sector, he reiterated skepticism about certain renewable energy sources, and criticized wind power in particular.

The speech was one of the most closely watched moments of the Forum, both because of Trump’s high profile and because his policy positions, particularly on Greenland and transatlantic relations, were seen as potentially disruptive to longstanding alliances.

This speech followed immdiately by that of Mark Carney Pime Minister of Canada whose address was entitled; “Principled and Pragmatic: Canada’s Path”. Carney’s speech was delivered amid escalating tensions between Canada and the United States over trade and sovereignty. Throughout the prior year, the US President had repeatedly threatened to impose tariffs on Canadian goods and made comments about making Canada the “51st state.

In a veiled denunciation of United States policy Carney called to action and advocated greater cooperation between the world’s middle powers , and argued that middle powers should “stop pretending” the international rules-based order still exists and accept that they live in a “might makes right” world. He underlined that as a result of ongoing erratic shifts in U.S. policies, the rules-based world order of the post–Cold War era, enabled by “American hegemony,” had experienced “a rupture, not a transition,”.He called on middle powers to unite against economic coercion from great powers, which “have begun using economic integration as weapons, tariffs as leverage, financial infrastructure as coercion, and supply chains as vulnerabilities to be exploited.”

Carney argued that if middle powers unit in the face of this perceived geopolitical shift, then they had much to gain In this rhetorical punch to America, he explained why continuing to appease the U.S. under present presidency would never work; where the status quo has left middle powers with insufficient leverage. He referred to how middle powers can change this by charting their own course in coalitions of like-minded states, and added : “if we’re not at the table, we’re on the menu.” Carney ended his statement by empasising that Canada intends to lead the way in the effort to create a genuine cooperation.

Carney’s speech was brilliantly conceived. Despite the resounding reception it received at the Forum, it reportedly angered the U.S. President and altered the tone of U.S.–Canada relations. Notable developments included the rescission of Canada’s invitation to the “Peace Board”, the establishment of which had been announced by President Trump at Davos, indications of significantly higher tariffs on Canadian goods, with figures as high as 50 per cent being mentioned, and subsequent punitive aviation-related measures, including the grounding of large numbers of Canadian-made aircraft and helicopters.

Recent reports of U.S. contacts with groups advocating enhanced autonomy for Alberta have also introduced a delicate sovereignty dimension into Canada-U.S. relations.

In the current period of geopolitical and environmental uncertainty, particular significance emerges from the evolving positions of major powers in global climate governance. As the United States signals a partial retreat from ambitious climate policy commitments, China has increasingly articulated its intention to assume a leading role in the global transition away from fossil fuels and toward renewable energy technologies, many of which are domestically produced. Within this context, China’s weight in international climate deliberations cannot be understated. Home to approximately 1.4 billion people, the country accounted for nearly one-third of global greenhouse-gas emissions in 2024, making its policy trajectory decisive for the effectiveness of global mitigation efforts.

At the United Nations Climate Summit last September, President Xi Jinping announced plans for China to begin reducing overall emissions by 2030, a declaration widely interpreted as a signal of strategic recalibration.

Complementing this position, Vice Premier He Lifeng, in his address to the Forum, portrayed China as a pillar of stability and a firm defender of multilateral cooperation in an increasingly fragmented international landscape. In reference to renewable energy he touted the economic potential of wind, solar and battery power. He emphasised the role of China in the world renewable energy system and the most complete new-energy industrial chain. He invited entreprises from all over the world to embrace the opportunities from the green and low-carbon transition, and work closely with China. He also mentioned that today China is the world’s top manufacturer of batteries, solar panels and electric cars.

These and other remarks positioned China to fill the void in energy-transition leadership at the Forum left unattended by the United States and some other Western countries.

At Davos 2026, Mark Carney articulated what many analysts now agree is a transformative moment in global order.

The rules based international order built in the post Cold War era, where U.S. leadership and multilateral institutions anchored stability, is no longer reliable or sufficient. Mr Carney stressed that middle powers (e.g., Canada, EU states, others) should form coalitions with shared interests and values rather than wait for great power benevolence.

This framing isn’t just rhetorical, it reflects a broader transformation in how states conceive of power: from reliance on superpower patronage to strategic autonomy and flexible coalitions.

This modularity is a feature of the new order, not an accidental side effect. Middle powers excel in it because they can straddle interests and avoid zero sum bloc logic.

As it has become evident, global order is undergoing a structural shift from U.S.-centric unipolarity toward distributed, modular multipolarity. Middle powers, including the EU, India, Canada, South Korea, and key Latin American states, are asserting agency through targeted trade deals, coalition-building, and issue-based diplomacy.

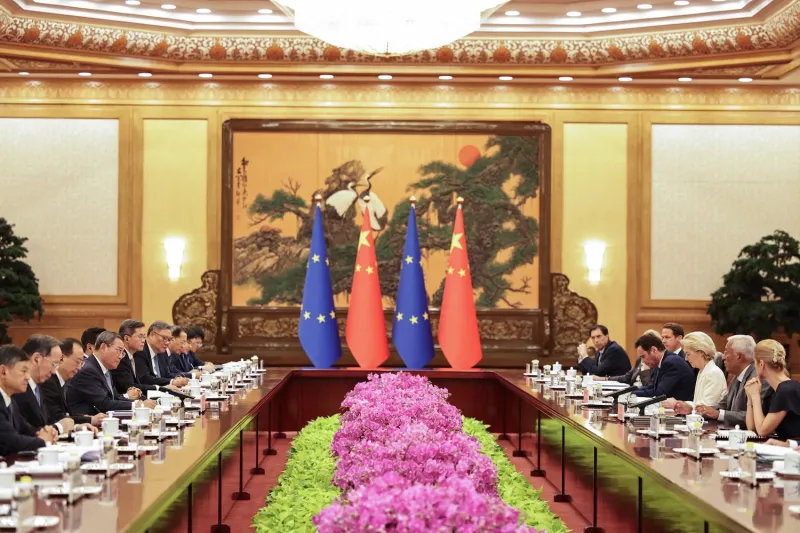

Latest developments, including the EU-India free trade agreement, Canada, Great Britain, Germany, France and others bilateral overtures to China, and reviving long-stalled Mercosur-EU talks, illustrate this realignment in practice, which accelerated strategic diversifications among middle powers.

Simultaneously, unpredictable actions by great powers e.g. renewed U.S. tariffs on South Korean exports has undermined predictability of long-standing alliances, and sparked Seoul’s push toward ASEAN and EU trade diversification have.

These quick shifts in the global system expedite moving from a U.S.centric order to a multipolar landscape where; China continues its Belt and Road Initiative and expansive economic diplomacy, enrolling over 140 countries; India now chairing BRICS tries to become a central pivot, balancing ties with the West, East, and Global South, regional powers like the EU, South Korea, and Southeast Asian states are expanding their independent roles and on track to prove that middle powers are no longer peripheral but, they are conduits of cooperation across blocs and can shape norms when superpowers diverge.To these we might add the latest developments about rapproachment between UK and EU on joining defence funds.

These developments are not idealistic; they represent a functional adaptation to a fragmented power landscape. They signal a move from institutions to coalitions. As a result, the shift is not toward new universal frameworks but toward layered, issue-specific coalitions anchored by mid-sized powers. At its center, trade as geopolitics serves a broader function: building autonomy, de-risking supply chains, and shaping standards within a multipolar order in which authority is shared across regional and thematic blocs.

Let us examplify these developments by new trade pacts between Eu and India as a pivot point. After 18 years of on-and-off negotiations, India and the European Union announced a mammoth free trade agreement that could slash tariffs on almost all goods. If the deal is ratified and implemented, it will create a free trade zone covering some 2 billion people and one-quarter of global GDP. Policymakers and analysts on both sides hailed the pact as a major win, with European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi calling it “the mother of all trade deals.”

Others include climate clubs, such as EU carbon-standard groupings with partner countries, as well as defence or technology coalitions, including Quad-like frameworks with adaptable membership. These arrangements are typically issue-specific rather than comprehensive strategic or transboundary pacts. Nevertheless, such pacts emphasize shared interests without requiring full alignment on all issues. In this space, middle powers can act as brokers across blocs and help reduce zero-sum pressures between great powers.

This dynamic also reflects a broader pragmatism: the EU–India partnership is “modular”, strong where interests align (trade, technology, resilience) and deliberate in managing structural differences (geopolitics and security priorities).

New Delhi and Brussels have agreed a trade deal that will eliminate up to €4bn of tariffs on EU exports and could double shipments from the bloc to India.

The World Economic Forum concluded without a formal declaration or negotiated communiqué, consistent with its long-standing role as a convening platform rather than a decision-making body, it was not to provide the answers, but to create the conditions under which deeply polarized actors could begin to live the most consequential questions of our age.

At the closing, messages emphasized dialogue, reflection, and continued engagement, underscoring both the Forum’s relevance and its limitations in a fragmented global context. The absence of a collective statement is itself indicative of the current international political and diplomatic climate. while Davos could probvide a critical space for exchange among political, economic, and social leaders, the conditions necessary for shared commitments and unified direction remain elusive. The Forum thus ended not with consensus, but with an acknowledgement of uncertainty, and a forward-looking emphasis on sustaining conversation amid deepening geopolitical, economic, and institutional divides.

A brief analysis of the debates and their outcomes nevertheless could justify these conclusions:

Globalization is no longer assumed to be stabilizing; it is increasingly viewed through the lens of vulnerability, dependency, and strategic risk.

Climate alignment is no longer treated as a shared horizon, but as a contested priority competing with security, growth, and political stability.

Technology is no longer framed primarily as a collective opportunity, but as a disruptive force requiring containment, regulation, and geopolitical positioning.

As is, the post-Cold War, U.S.-anchored international system is giving way to a new, more diffuse and modular global architecture.

In today’s ever-changing and unpredictable world, I do not see a clean replacement of the old order. As Mark Carney puts it, “We actively take on the world as it is, not wait around for the world we wish to be.”

Should we then accept the reality of a “rupture” with all the principles and disciplines we once considered vital to our existence? Should we accept that a genuinely new structural order will not be fully in place within a single year, or even a few? Or should we instead understand the present moment as the entry into a phase of distributed cooperation marked by multipolarity, strategic pragmatism, and issue-specific coalitions?

The evidence increasingly points to the latter. We are now witnessing a layered architecture in which regional governance, the EU, ASEAN, the African Union, grows stronger. Free-trade agreements such as EU–India arrangements, Indo-Pacific engagements, Middle East corridors, and regional standards frameworks are forming far more rapidly than five years ago. Issue-specific networks, climate clubs, digital trade standards, and technology norms, increasingly eclipse universal structures, while flexible minilateral coalitions coordinate responses where consensus among great powers is missing. The expansion of middle-power groupings around AI governance, energy security, and digital standards, together with responses to crises, wars, supply shocks, and climate emergencies, forces realignments at a pace faster than deliberate designs.

At the center of this transformation are middle powers, states that lack superpower status but possess the diplomatic agility, economic leverage, and normative influence to shape emerging frameworks. As Mark Carney emhasised their collective strength lies not in challenging hegemony, but in constructing alternative pathways for cooperation, grounded in shared interests rather than great-power dependencies.

This new order is not defined by formal blocs or universal institutions. Instead, it adopts frameworks that are modular and adaptable, pragmatic, strategic, and built to endure structural differences rather than erase them.

Topical News See more