The President of the US-China Business Council: The Impact of Decoupling on US Employment

“The transition in trade policy from the Trump era to the Biden era, while maintaining certain themes, will be very different. In terms of employment, the trade war caused job losses and the Phase One agreement and the elimination of tariffs on both sides will lead to job creation. Ten policy recommendations suggested by the author provide a guideline for job creation through deescalation of the trade war, a transition to Phase Two negotiations and a lifting of travel restrictions on both CCP members and students to the US.”

—— Craig Allen, the President of the US-China Business Council.

US–China relations in the early days of the Biden Administration present a difficult conundrum.

Speaking at the State Department on February 4th, President Biden said, “Every action we take in our conduct abroad, we must take with American working families in mind.” Full employment is a key goal of this Administration.

In the same speech, the President said, “We will confront China’s economic abuses; counter its aggressive, coercive action; to push back on China’s attack on human rights, intellectual property and global governance.”

There is built-in tension between these two sets of foreign policy objectives. How will the United States maximize economic employment for Americans while disagreeing with and confronting China where it thinks it must? It will take deft diplomacy to accomplish both goals.

This chapter will offer ten policy suggestions on how to maximize employment in the United States by leveraging China’s growth without compromising US geopolitical or diplomatic objectives.

There are, however, three big caveats.

The first caveat is that the correlation of trade policies to specific outcomes in the labor market is weak. President Trump, for example, pursued a protectionist trade policy yet employment in the pre-Covid period was strong. President Trump was on track to add some nine million jobs, mostly due to a combination of loose fiscal and monetary policies, as well as de-regulation. Trade policy does have an impact on employment, but it is relatively small; the tail being wagged by the dog.

The second caveat is that future technological change will impact the US labor market in ways that are impossible to predict. The future of autonomous driving, for example, will have a far larger effect on employment than trade policy.

But technological competition is also a key element of US–China relations. China’s technology policies of “self-reliance and self-strengthening” are of course relevant and will be discussed later.

The third caveat is that distortions in China’s domestic macroeconomy are also pertinent when examining US trade policy toward China.

In 2007, Wen Jiabao described China’s economic growth as “unstable, unbalanced, uncoordinated and unsustainable.” Premier Wen’s observation is probably as true now as it was when he said it—and this has profound implications for policy makers around the world.

In summary, China’s household consumption is far too low; it was less than 40% of total GDP in 2020. This contrasts with between 60 and 70% in OECD countries. From a comparative perspective, China hugely over-saves and over-invests in often uneconomic infrastructure at the expense of family consumption. This drives over-capacity, over-investment, and (implicitly) subsidized exports—at the expense of both Chinese workers and consumers, and China’s foreign trade partners.

The good news is that the Chinese government recognizes these imbalances and has articulated an intention to address the underlying issues.

At the National People’s Congress in March, a “dual circulation” policy was introduced along with plans to expand consumption as a percentage of GDP. Will these policies help grow the middle class and actually raise consumption as a percentage of GDP? Will they be WTO compatible? What will the impact be of the “dual circulation” policy on China’s trading partners?

The transition from an economy based on capital investment and net exports to one based on domestic consumption will be a difficult and long-term process for China. China will need to move as much as two to three percentage points of GDP from investment to consumption each year for ten years if it is to escape Wen Jiabao’s “unstable, unbalanced, uncoordinated and unsustainable” paradigm.

1. Trade Policy and US Employment

Having recognized the primacy of macroeconomic adjustments in the United States and China, the focus now is on trade policy. Notwithstanding the importance of macroeconomic adjustment and changing technology, trade policy will continue to impact employment in the United States.

Future economic historians will look back at the Trump Administration with interest for its many innovations in trade policy. The last four years provide much data on the costs and benefits of tariffs and other protectionist policies.

While the benefit of sufficient hindsight is not yet available, evidence suggests that—despite what may have been the best of intentions—tariffs and other tools of the Trump era trade war had a very negative net impact on US employment.

It is true that some jobs may have been created. But it is certain that many more jobs were lost as a result of the tariffs.

Ambassador Robert Lighthizer and Professor Peter Navarro would likely discuss the jobs in aluminum smelters and steel mills that were saved. What they might not share is that each job saved in those industries cost USD 900, according to Chad Bown of the Peterson Institute.

In manufacturing, the hit to US employment has been direct through decreased exports and indirect through declines in total factor productivity and competitiveness. Described here is an example of a company that lost sales and market share due to the tariffs:

A tool maker imported parts for tools from China, assembling them in the US and then selling his branded tools around the world. When tariffs were introduced, many of the components his company needed were hit by 25 percent tariffs and alternative suppliers at a good price could not be found. As they were manufacturing in the US with Chinese components, they had to raise prices and subsequently lost market share in the US market and abroad to competitors, making everyone in the US worse off.

This type of story was repeated ten thousand times across the US manufacturing sector.

USCBC recently commissioned Oxford Economics to study the impact of the tariffs on employment. It concluded that, at the height of the trade war, approximately 245,000 American jobs were lost.

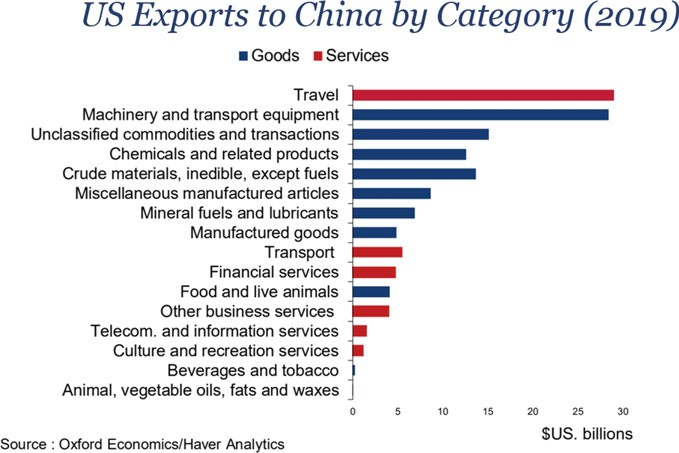

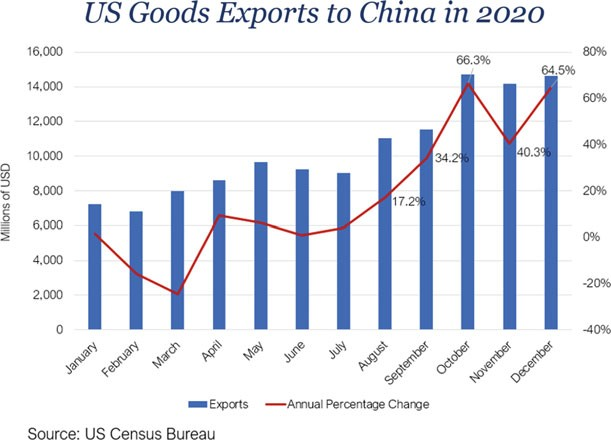

The following charts describe the industries and geographies where jobs were lost due to Trump’s trade war. The first chart shows total US exports by category to China. Services are a vital part of the export mix to China, making up as much as 40% of our total exports—and they had been growing rapidly.

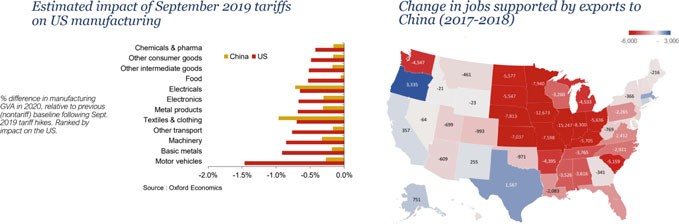

The second chart focuses on the manufacturing sector in both China and the United States, showing the impact of the trade war on these sectors in terms of gross value added. This chart demonstrates well that Trump’s tariffs had their intended effect in China: Chinese GVA declined in all these industries. But, in all cases, US GVA in the same industries also declined…sometimes more and sometimes less. Both sides lost.

The third chart shows the unequal effect of the trade wars on employment from a regional perspective. The underlying data are only on job losses or gains from US exports to China; total factor productivity is not included. Nonetheless, it is instructive that the impact of these trade policies was the most severe for those states that rely most on commodity production and manufacturing.

Excessive reliance on bilateral tariffs on our trading partners typically rebounds on American farmers in the grain-growing areas of the US Midwest. When other countries retaliate against the WTO-illegal use of tariffs by the United States, they retaliate by hitting American farm exports—as this is where they will have the biggest political impact.

President Trump spent some USD 28 billion compensating American grain farmers for their losses. But the compensation was unevenly distributed and it could not nearly make up for the lost, hard-earned market share and these farmers’ long-term prospects for selling in China and elsewhere.

These subsidies make the unemployment effect of the tariffs on American farmers very hard to calculate. By way of example:

In 2018, a small American dairy family in Wisconsin had to sell his 80 cows to a neighbor with 800 cows due to low prices that were partly caused by retaliatory tariffs that the Chinese put on US dairy. The farmer then took a job as a long-distance truck driver. While he was not technically unemployed, the composition of the labor market changed.

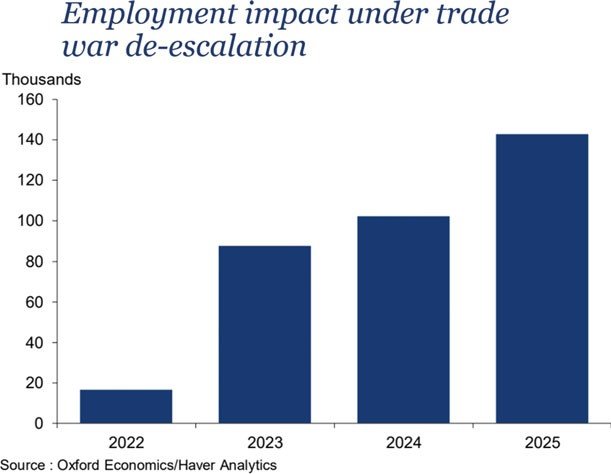

Finally, Oxford Economics also projected the economic and employment impact of de-escalating tariffs from 2022 to 2025. The assumption underlying this graph is not the total removal of tariffs, but rather a reduction of bilateral tariffs from the current average rate of 20% to a more moderate 12%. This would lead to 145,000 new jobs by 2025.

If the assumption is changed to a total removal of the tariffs and the counter tariffs, the total job gain would be much higher—but difficult to estimate exactly.

2 Ten Policy Prescriptions to Maximize US Employment

The examined data provide the background for the following policy prescriptions:

First, the United States and China must reinstate a forum to discuss important macroeconomic issues that impact the well-being of the other. There is an urgent need to reestablish regular dialogue to recognize—and perhaps shape—macroeconomic decisions to be made in the United States and China. A format like the Strategic and Economic Dialogue would, for example, allow the United States to better understand Chinese decisions that will affect US employment while providing technical support to assist China in adjusting its economic model toward greater consumption as a percentage of GDP. Alternatively, more narrowly defined technical dialogues could be instituted to address and resolve specific problems.

Specific issues that could be discussed regarding excess savings could include:

–Winding down industrial overcapacity

–Improving the social safety net

–Preparing for a rapidly aging society

–The misallocation of capital to SOEs and their corporate governance

–Greater transparency for government subsidies to ensure WTO compatibility

–Abolishing the hukou system

Another reason to reintroduce regular dialogue with the Chinese government is the need to change the bilateral conversation from protectionism and containment. A more realistic and pragmatic conversation is needed to ensure that China’s rise is peaceful and not deleterious to China’s neighbors and trading partners. The question is how to square a state- and party-run economic system within the global system that the WTO envisaged.

These are big issues without easy answers. But talking is better than not talking.

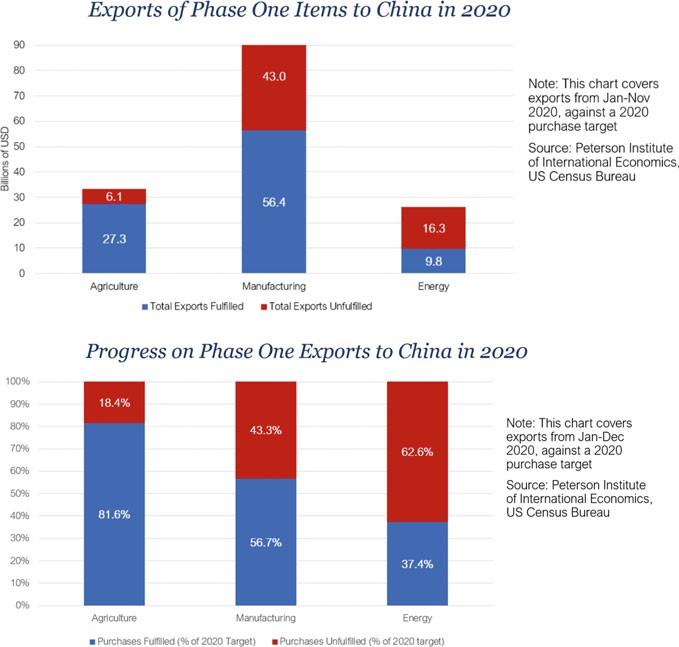

Second, we should maintain and fully implement the Phase One deal. Phase One has many critics who note that the Chinese have only met approximately 60% of their purchase obligations under the first year of the deal.

Chinese government officials have said that China fully intends to meet its commitments under the deal, and this should be encouraged. USTR, DOC, DOE, and DOA should initiate negotiations to understand when and how the Chinese will meet these obligations. If successful, this would lead to a significant increase in US exports and much-needed jobs over the 2021 calendar year.

Perhaps even more important for the longer term, the Chinese government has met its commitments under the deal to change Chinese policies to improve market access for American agriculture and financial service firms. It has also increased protections for intellectual property. Much progress has been made in these areas; this progress should be defended and expanded.

The Phase One deal is only in place until the end of 2021. This leads to the third recommendation.

Third, negotiations on a Phase Two agreement should urgently be started so that these talks can be completed prior to the expiration of Phase One. A target date for completion would be when President Biden and President Xi meet on the margins of the Annual APEC meeting to be held November 10–13, 2021 in New Zealand.

The issues that were not resolved in 2019 relate to state-owned enterprises, subsidies, industrial technology policy, and cyber. While all of these issues are very difficult, the Chinese side has indicated that it is willing to discuss the problems. The China–EU Comprehensive Agreement on Investment, though not yet ratified, contains modest commitments on SOEs and subsidies.

The United States could reach back to the Bilateral Investment Treaty negotiations and ask the Chinese to bring forward commitments made at that time. The Obama–Xi cyber agreement could also be resumed. While negotiations would be difficult, it is possible to make incremental progress on all of these issues.

The Biden Administration might not wish to call this a Phase Two agreement; it could be a succession of smaller agreements on specific topics. But some momentum in bilateral trade negotiations must be created and the previously agreed-upon road map might be helpful in this regard.

Fourth, tariffs on both sides should be eliminated. Tariffs on goods going both ways across the Pacific are currently at an average of about 20% and there is a danger that they could become permanent if they are not addressed soon. Tariffs tend to be easy to put up and sticky to come down. The longer they are up, the harder they are to bring down.

Tariffs are job killers that simultaneously impoverish consumers in both the United States and China. If these tariffs become permanent, they will distort US–China trade and investment—possibly in perpetuity, condemning bilateral relations to an instability from which it might be difficult to recover.

USCBC research suggests that if the tariffs were lowered to 12%, there would be a net gain of about 145,000 jobs by 2025. If the tariffs were fully removed, especially in concert with incremental improvement on the outstanding issues, these job gains would be much higher.

Fifth, following the completion of Phase Two negotiations and the elimination of tariffs, negotiations should continue, using the CPTPP as a discussion framework. Asia’s economic architecture today is starkly different to the situation four years ago. The Chinese and their partners have successfully concluded a 15-country RCEP (Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership) agreement. The Chinese and the Europeans have concluded a Comprehensive Agreement on Investment that is awaiting ratification. Belt and Road investments have further strengthened regional economic integration. China’s trade negotiators have been extremely busy..

Finally, President Xi and Premier Li have both stated that China will consider entering the CPTPP (Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership). They should be taken at their word. Chinese economists have commented that this would be the next logical step in China’s reform and opening program. While China’s entry into CPTPP will certainly take time, neither their ability nor their determination to do so should be doubted.

While it is not politically feasible for the United States to consider joining the CPTPP in the near term, perceptions may change if China appears to be moving to join the group without the United States. If China were to accede without the United States also joining, the United States would be locked out of Asia—the world’s fastest-growing market. This would be a historic turning point and it might be difficult for the United States to recover from this situation.

To hedge against this risk, it makes sense for the world’s two largest economies to talk with each other in terms of the rules associated with an agreement that they may both—one day—join. The CPTPP is largely based on US trade law and it closely complements the USMCA (US–Mexico–Canada Agreement).

This recommendation is long-term. The employment effects of joining CPTPP cannot be clearly known at this point. However, a strategy to move forward is needed and, in the view of this author, having discussions with the Chinese structured around the CPTPP is in America’s long-term economic interest.

The next three recommendations are much more short-term, and they lie outside the traditional bounds of trade diplomacy, but they would have immediate quantifiable benefits for American workers.

Sixth, in preparation for the post-COVID world, visa restrictions against CCP members should be removed and Chinese tourism to the United States should be facilitated. Travel and tourism is the single largest US export to China, worth as much as USD 30 billion a year prior to COVID-19. However, the Trump Administration put into place restrictions on 92 million CCP members and their families visiting the United States. These regulations are offensive, as well as completely unenforceable, and they should be abolished immediately.

Travel and tourism is a very labor-intensive sector and continued expansion of these services to Chinese nationals would especially benefit lower-income Americans, such as those working as waiters, drivers, in retail, or in the hotel industry.

Undoubtedly, demand for these services and continued expansion of this market are likely in the post-COVID era—if the US government gets out of the way. Abolishing the visa restrictions on CCP members and their families would be smart and easy, and it would generate income for hundreds of thousands of Americans,especially those whom the pandemic has hurt mostly badly.

Seventh, the Biden Administration should be clear that civilian Chinese students are welcome at American universities in all fields that are not directly related to national security. Education is roughly a USD 15 billion-dollar export market and Chinese students remain committed to studying in the United States, if they know that they are safe and welcome. There are many competitors wishing to supplant the United States in this market, and we must not be complacent.

Excesses and inappropriate behavior by Chinese researchers at American institutions have been well reported. It is also clear that China’s Thousand Talents campaign is insufficiently transparent and induces researchers into relationships that may be improper. But it is also true that the US response to such excesses has led to unfair treatment of individual Chinese and Chinese American academics.

Universities and research institutions should deal with these problems by tightening governance, reporting, and ethical procedures, while maintaining academic freedom and expanding collaboration and technical exchange with civilian Chinese counterparts.

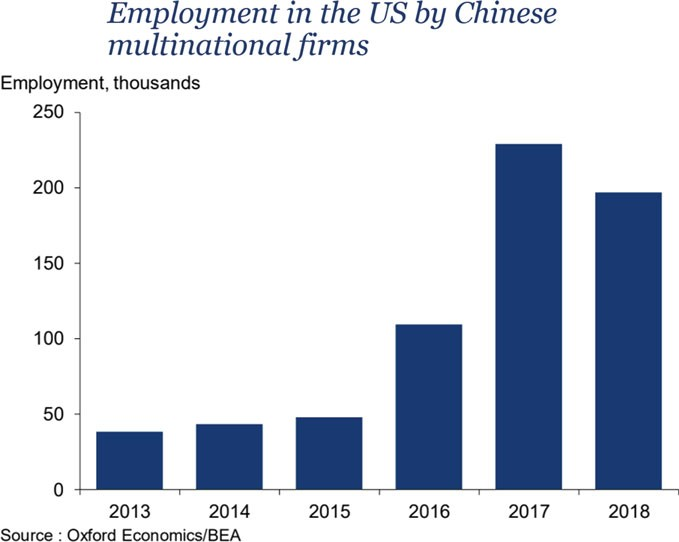

Eighth, Chinese investment in the United States should be welcomed in all industries and localities that do not have clear national security implications. US economic history shows that countries with large trade surpluses eventually invest in our markets to make products here. This industrial migration is positive. It helped to mitigate tensions with Japan in the 1970s and Taiwan and Korea in the 1980s and 1990s.

Today, more Chinese investment in the United States is needed, particularly in areas that have high unemployment and suffer from chronic underdevelopment.

There is a huge demand in China to invest in the United States in industries that mostly have no national security implications. The US government should welcome such investment. Mayors and governors want Chinese investment in their jurisdictions, while the federal government appears less keen. The implications for US employment are some 30,000 fewer jobs in 2018 compared to 2017.

CFIUS and FIRRMA, the US’s regulatory regimes for in-bound investment, are necessary. However, they have been applied in a manner that suggests that the Federal Government wants to limit investment from China to as little as possible. This is counterproductive. It hurts American workers.

To be balanced, it should be noted that the Chinese government has also been regulating outbound investment to the United States and elsewhere, so US policies are not the only impediment.

Nonetheless, if Chinese investment into the United States is not allowed, the United States is condemning itself to long-term economic imbalances with China. This is not a future to which we should aspire.

Ninth, supply chain resiliency issues should be addressed with incentives rather than trade-distorting tariffs or other government-mandated barriers. As a result of COVID and a concern for potential shocks to the US supply chain, it is reasonable to aspire to greater resilience and flexibility—to ensure the continued flow of critical goods in times of emergency. However, the US government should be extremely careful before using coercive tactics to reshore manufacturing or force companies to produce in a particular place.

Tariffs are an incredibly blunt instrument. There are precious few cases where tariffs have incentivized manufacturing investment in the United States. Yes, the tariffs have moved manufacturing from China to ASEAN countries. But does that really help resilience? Does it help employment in the United States?

If the US government wishes to induce companies to invest domestically, it should provide WTO-compliant incentives toward this end and allow companies to decide what to buy and where.

Finally, the challenges of data, export controls, and technology policy need to be addressed more comprehensively—preferably in alignment with Europe and Japan. Technology is the most difficult and important element of the bilateral relationship, especially over the long term.

There should be zero doubt that the Chinese also believe that technology self- reliance and self-strengthening is a key national objective. It is unfortunate that Chinese policies associated with technology self-reliance and self-strengthening are so often WTO-illegal and outside of OECD norms. In addition, the Chinese R&D establishment is too often plagued by waste, fraud, and abuse.

In addition to the trade policy and governance problems associated with tech in China, there is also the specter of civil–military fusion and the Chinese Intelligence Law, both of which cast a chilling light on any civilian technology cooperation with Chinese universities, institutions, and academics. China should reconsider these laws; they are complete global outliers and are not found in any other country.

Without being naive, there is some degree to which international negotiations and better bureaucratic hygiene could lead to China transitioning from playing a predatory role in the global economic ecosystem to playing an integrated and trusted partnership role along with the world’s other great research countries. It is in the interest of Chinese civilian institutions to better integrate with global R&D norms, values, and procedures.

As this issue is so critical and multi-dimensional, I believe that the establishment of a new office in the White House to coordinate global technology and data policy is necessary. Its first job would be to coordinate the dozen or so agencies that are involved in this matter.

In addition, the office could coordinate with US allies. It should also negotiate with the Chinese and others on the rules of the road for technology cooperation, for technology competition, and, most importantly, for mechanisms to enforce such rules.

Technology is the most difficult issue in US–China relations and a much more focused, coordinated, and sophisticated approach to this subject is needed within the US government. This issue is long-term, so investing in its proper management would be prudent.

Better coordination among countries would help. Common standards on export controls, common standards on in-bound investment, and, if possible, a common research and development agenda and budget should be our goals.

3 Conclusion

In summary, the policy ideas outlined here would help to grow employment in the United States over the short, medium, and longer terms, without prejudicing overall geopolitical and diplomatic challenges with China. The ten policy recommendations made here would lead to a much healthier American economy and job opportunities for American citizens.

The United States and China have a complex security and economic relationship. The overall dynamic of the relationship must be changed to be more competitive and less confrontational, while being mindful of both countries’ security and economic needs and trying to bridge differences whenever possible.

Craig Allen is the President of the US-China Business Council, a private, nonpartisan, nonprofit organization representing over 200 American companies doing business with China. Before joining the council, Craig had a long, distinguished career as a US diplomat serving around the world, mostly in Asia. From 2015 to 2018, Craig served as the United States ambassador to Brunei Darussalam. He is also a former Deputy Assistant Secretary for Asia at the US Department of Commerce’s International Trade Administration and a former Deputy Assistant Secretary for China.

// Editor’s note

Transition and Opportunity: Strategies from Business Leaders on Making the Most of China’s Future is the third book in the “China and Globalization” series, published in partnership with Springer Nature. The 22 essays contained in this volume are the work of a wide range of global experts in China’s business community. Contributors include the leaders of international chambers of commerce, CEOs and senior executives from leading MNCs and industry experts or country heads from global consulting firms. In a world of constant change and uncertainty where there is so much in doubt, these perspectives on the future of business in China, which are rooted in real-world experience and proven strategies that work, provide an immense trove of knowledge for those looking make the most of China’s bright future.

Transition and Opportunity

Editors: Huiyao Wang, Lu Miao

Published in February, 2022

Publisher: Springer Nature Publishing Group

Download Book at Springer

https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-981-16-8603-0

Transition and Opportunity: Strategies from Business Leaders on Making the Most of China’s Future is the third volume in CCG’s “China and Globalization” series of books edited by Dr. Huiyao Wang and Dr. Lu Miao.

Series Editors: Huiyao Wang Lu Miao

Publisher: Springer Nature Publishing Group