Wang Huiyao: New Chapter in China-Japan Relations Can Drive Asian Integration

June 29 , 2019By Wang Huiyao |

President of the Center for China and Globalization(CCG)

While eyes will be focused on the China-U.S. meeting that will take place on the sidelines of the summit, the quietly gathering momentum for Asian integration may prove to have far greater lasting significance for the world.

President Xi Jinping’s attendance to the G20 Osaka Summit, also marks a new dawn of opportunity for China-Japan relations. By working together, Asia’s two largest economies can be a driving force for integration on the continent. At the global level, a more cohesive Asia built on solid China-Japan ties can also provide sorely needed impetus for free trade and global governance.

While eyes will be focused on the China-U.S. meeting that will take place on the sidelines of the summit, the quietly gathering momentum for Asian integration may prove to have far greater lasting significance for the world.

A Marked Period of Warming in China-Japan Ties

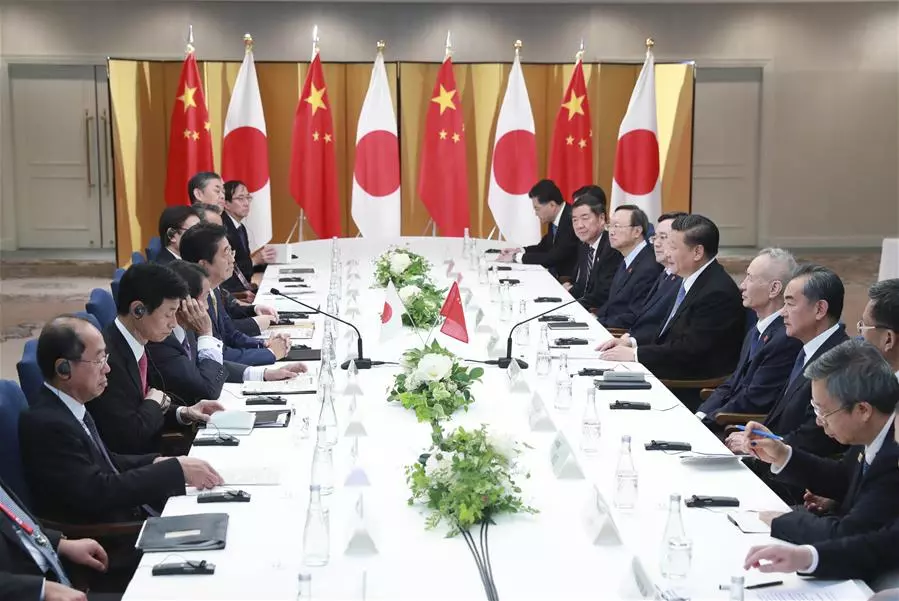

Xi’s attendance in G20 Osaka Summit will cap a marked period of warming in China-Japan ties over the past two years. On the 40th anniversary of restored bilateral ties last year, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang visited Japan in May, followed by Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s trip to Beijing in October.

The resumption of high-level diplomatic exchanges comes amid a revival of two-way trade and investment and growing financial cooperation. Last year, a bilateral currency swap exchange agreement was signed, and this week, the China-Japan ETF Connectivity scheme, which links the Shanghai and Tokyo stock exchanges, was launched.

Meanwhile, the deep cultural ties the two countries share are thriving once again. The number of trips by Chinese tourists to Japan could reach 10 million this year, up from just 1.4 million in 2012.

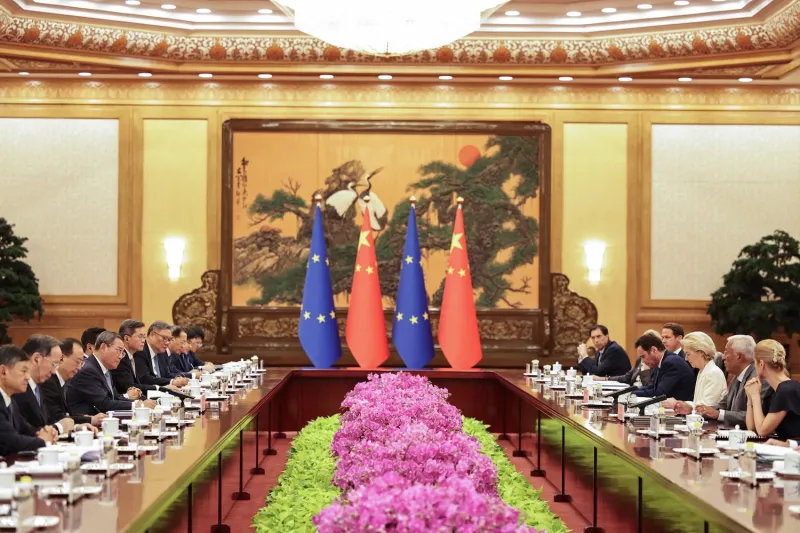

Chinese President Xi Jinping meets with Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in Osaka, Japan, June 27, 2019. (Xinhua/Pang Xinglei)

So what explains the turnaround in relations between Beijing and Tokyo? Undoubtedly, geopolitics have contributed to the thaw.

With its doctrine of “America First” and trade attacks on China and Japan, the U.S. under President Donald Trump has increased significant uncertainties and challenges to the world multilateral trading system, and pushed Asian countries to look closer home in the quest to maintain free trade and multilateralism.

Previously, Tokyo’s close ties with Washington were a constraint on China-Japan relations and Asian-led regional integration. Now, the U.S. has helped bring China and Japan together.

However, the China-Japan rapprochement is far more than merely a thaw of convenience. Despite a complicated history, China and Japan, as the largest economies in Asia and shared proponents of free trade, have deep cultural ties and shared interests that go far beyond the current geopolitical shift.

For the U.S., a role in Asia is a strategic choice. For China and Japan, it is an enduring geographic reality.

Since the U.S. abandoned the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), Japan has emerged from its subordinate role and charted a more independent course toward an Asian future. This is most evident in Tokyo’s role in the TPP, which came to life at the start of the year as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).

Shared Interests and Opportunities for Cooperation

The changing geopolitical situation and rise of Asia provide a window for China and Japan to put differences behind them and develop a stronger relationship – a “new historical starting point” as top Chinese diplomat Yang Jiechi said recently.

Working together, the two largest Asian economies can provide the political and economic drive for integration in Asia. Proactively nurturing shared interests can help lock the relationship toward a positive trajectory. There are several aspects to prioritize.

First, China and Japan can work together through platforms such as the G20 to promote badly-needed reform of the World Trade Organization (WTO). It is necessary to capture the shifting patterns of economic activity, such as services and the digital economy, and to revive the incapacitated dispute settlement mechanism. As representatives of developing and industrialized nations, China and Japan, respectively, can work together to help forge a consensus on the way forward.

Both sides should also galvanize efforts to conclude regional trade agreements. Asia is bucking the global trend of trade fragmentation and giving momentum to trade liberalization. Beijing and Tokyo can help continue this by accelerating joint efforts to complete the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and the trilateral free trade agreement they are both pursuing along with the Republic of Korea.

In addition, China should strongly consider joining CPTPP. This would give China access to a dynamic market representing some $10 trillion of global GDP and could form a solid bedrock for deepening China-Japan economic relations. With the U.S. out, the CPTPP currently lacks the kind of massive consumer market that China can offer. China’s accession fits economic logic and would make the living agreement all the more attractive to new members.

Joining this high-standard trade agreement would also give China external impetus for the next phase of reform and opening-up, just as WTO entry did two decades ago. For example, the CPTPP’s emphasis on services fits with China’s evolving economic structure, while its principles for state-owned enterprises (SOEs) align well with China’s aims to develop the private sector and reform SOEs.

Aside from trade liberalization, the other key to the puzzle of Asia’s economic integration is infrastructure. Asia’s infrastructure gap remains very big and is set to grow linearly to $252 billion by 2040, according to a report released by the Boao Forum for Asia this year.

Joint Work in Asian Infrastructure Building

Some paint China and Japan as locked in an “infrastructure race” in Asia. In reality, Asia’s infrastructure needs far exceed the supply capabilities of any single country. By combining their expertise and resources, China and Japan can help overcome this gap.

Through positive network effects, infrastructure gains value as complementary pieces of the connectivity puzzle are built around it. While a highway by itself is not much use, coordinated large scale investment can unlock “infrastructure dividends” and link all corners of the continent.

If Japan joins the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, it would be a great step forward for cooperation, and there have been some promising signals from Tokyo on this matter. There is also plenty of room for Chinese and Japanese firms to work together on infrastructure projects in third countries in Asia, as laid out in a cooperation agreement signed by the two sides last year. Besides, China and Japan, as the largest share holders of Asian Development Bank (ADB), can also enhance cooperation in ADB.

Global governance, regional trade agreements and infrastructure building are just three of the promising areas for China and Japan to boost cooperation. By increasing dialogue, between governments as well as via non-governmental channels such as industry forums and think tanks, many more opportunities can be explored and tapped for mutual benefit.

Long before westerners came to this part of the world, Osaka was a hub in a thriving intra-Asian network where goods and ideas flowed between China, Japan and the rest of Asia. As the G20 meets in this storied port city, Asian leaders have the opportunity to build on this history of trade and regional integration, bringing benefits not only to Asia but also the entire world.

Topical News See more