Mehri Madarshahi: World Security Challenges and Alternatives

February 26 , 2023By Mehri Madarshahi, CCG Non-Resident Senior Fellow, Advisory Member of the UNESCO International Centre for Creativity and Sustainable Development .

Introduction

Against the background of the just concluded Munich Security Conference, and its global relevance, this article is a modified version of what will be printed by Palgrave publishing house this April with the title of “Pluralism and World Order”.

The 59thMunich Security Conference (MSC) took place from 17-19 February 2023 in Munich, Germany. The MSC 2023 was attended by leaders of major world powers, decision-makers, parliamentarians and business people. It offered an unparalleled platform for high-level debates on key foreign and security policy challenges of our time.

It was in early 1990s that the twin goals of peace and development became dominant factors within the world order. As a consequence of which, the “Agenda for Peace” was launched by the United Nations Secretary-General and approved by the Security Council to highlight the potential peace dividend for development. Although at the time peace and development were declared as two sides of the same coin, the third dimension of this equation, namely environmental degradation was not in the glare.

With heightened concerns about environment, the Member States of the United Nations (193+) unanimously approved and launched in 2015 what became famous as the “Agenda 2030” with its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The main objective of this major initiative was to tackle urgent problems associated with climate change and its impact on other challenges, such as increasing poverty, desertification, access to quality and equal education, extinction of biodiversity, pollution and hunger. Today, after the passage of some eight years, it has become clear that even though the ambitions have remained, progress on implementation of SDGs had been gradual or insufficient.

The Earth is rapidly losing its biodiversity at massive rates. One in five species on Earth now faces extinction. Scientists estimate that this will rise to 50% by the end of the century, unless urgent action is taken. Also, current deforestation rates in the Amazon Basin could lead to an 8% drop in regional rainfall by 2050, triggering a shift to a “savannah state”, with wider consequences for the Earth’s atmospheric circulatory systems.

The chemistry of the oceans is changing more rapidly than at any time in perhaps 300 million years, as the water absorbs anthropogenic greenhouse gases. The resulting ocean acidification and warming are rapidly leading to unprecedented damage to fish stocks and corals. Glaciers in Antarctica are melting, and water scarcity threatens to wipe out part of our civilization.

CO2 is on the rise owing to an anxiety for conserving and storing energy. In the absence of many sustained sustainable plans for alternative source of energy, fossil fuel again is considered a commodity and an easy means for energy consumption. In recent years, the world has generated around 500 tons of CO2 per US$1 million of the global GDP. In 2019, 40 billion tons of CO2 were emitted per US$88 billions of the world’s GDP. Global energy-related carbon dioxide emissions rose by 6% in 2021 to 36.3 billion tones, their highest ever level, as the world economy rebounded strongly from the Covid-19 crisis and relied heavily on coal to power that growth (IEA FLAGSHIP REPORT, MARCH 2022).

Perceptibly, as a result of emissions of carbon dioxide and other heat-trapping gases with humans indisputably the cause, the Earth’s climate is changingrapidly,

What will that mean? For the next 30 years or beyond, there will be more intense earthquakes, heat waves, more damaging droughts, and more episodes of heavy downpours that will result in widespread destructions and flooding in all continents.

These crises necessitate drastic emission cuts in the next 10 years in order to reach the long-term goal of net zero carbon emission.

In early 2020, the unprecedented outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic caused governments, businesses, societies, and individuals to grapple with its consequences. Low income and vulnerable populations suffered from job losses, mounting debt, and shrinking revenues. The pandemic obligated virtually most Governments, especially in the industrialized world, to develop recovery packages to the tune of trillions of US dollars. Yet, not all governments had the requisite resources to steer capital sustainably at such a huge scale to meet the emerging social needs.

The resulting economic downturn severely affected virtually all-important financial decisions and continue to date shape the global economy for the next decade. This will coincide with a period when all countries are expected to significantly reduce, if not cut by half carbon emissions in order to contain global warming within 1.5 degrees centigrade.

The pandemic forced many to search for new opportunities beyond their home base. This trend will be accelerated by massive climate migrations resulting from drastic climate-induced weather changes, coastal flooding, prolonged droughts, wildfires, or extreme pollution.

According to the World Bank, within the next decades, one billion people are expected to live in insufferably hot spaces. Rising sea levels also could contribute to displacement of the same number of people. Changes in precipitation may result in shortages of water in some 200 cities, heavily impacting food and water security of many countries and communities.

Covid-19 also impacted the international relations accelerating the transition to a more fragmented world order in which future organizing principles of the international system are becoming unclear. These factors are now exacerbated by the competitive, zero-sum dynamics unleashed by the present pandemic.

Be it Covid or the on-going conflict in Ukraine, the new geopolitical environment -with multiple poles competing and/or cooperating – it is difficult for any single country to exercise its will. Neither Russia, China nor the United States can emerge from the present fragilities as a “winner” in a way that would dramatically shift the balance of world power in its favor.

The outcome of the on-going geopolitical competition will lead to a fragmentation of power and will hinge on the relative economic recovery principally of the United States and China but also of other countries, especially in Europe and Asia.

Despite all challenges, the conditions of great power competition coupled with the economic pressures resulting from Covid-19, however, can create opportunities for seeking ground for cooperation on issues of common interest, such as tackling global crises.

At present, there is a significant potential to create an international center of gravity that can implement climate and health-related mitigation standards.Building on shared criteria and interests, therefore, can form the core of an institutional support ecosystem. Achieving this will require significant development resources and collective efforts by all stakeholders.

Such an initiative could re-engage development agencies and leverage the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

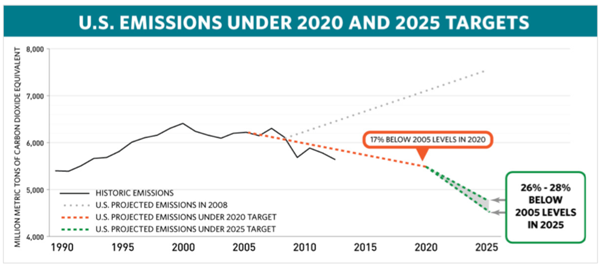

To turn the clock to 2014, or the time when the world witnessed a glimmer of hope in Sino-American cooperation may be a good model to follow. At the time, the US government made a strategic decision to announce jointly with China its Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC) under the envisaged Paris Climate Agreement. By this, the United States was to achieve an economy-wide target of reducing its emissions by 26–28 percent (below its 2005 level) by 2025 and China announced its intention to achieve the peaking of CO2 emissions around 2030 and to increase the share of non-fossil fuels in primary energy consumption to around 20 percent by 2030.

Source: United States Historic Emissions and Projected Emissions Under 2030 Target–USNDC

This joint announcement had a major impact around the world. It was the first time China had come forward so early and so willingly to announce its climate targets, and the first time the world’s two largest emitters had made such an announcement jointly. The announcement set the stage for other countries to refine the targets for their own climate strategies over the following months, so that by the time leaders gathered in Paris at COP 21 in December 2015, 180 countries (representing nearly 95 percent of global emissions) had already announced their own climate targets. This was crucial to building the international momentum that led to a successful conclusion of the new Paris climate agreement.

Following this success, on 15 October 2016, at the 28th Meeting of the Parties to the Montreal Protocol in Kigali, Rwanda (United Nations Environment Program 2017), 197 countries reached an agreement on amendments to phase down HFCs. Under the amendment, countries committed to cut the production and consumption of HFCs by more than 80 percent over the next 30 years. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimated that this phase-down schedule could avoid more than 80 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions by 2050 and avoid up to 0.5 degrees Celsius warming by the end of the century.

Developing countries were notably divided into two groups, with China falling into the first group of countries that had to freeze consumption by 2024, and India falling into the second group, that would be allowed to begin freezing emissions only by 2028. All developing countries were also eligible for financial support to aid in their transition away from HFCs.

At their meeting in March 2016, President Obama and President Xi committed to working together to reach a successful outcome that year on the ongoing negotiations and to reach a deal on a global market-based measure for addressing greenhouse gas emissions from international aviation, negotiated under the auspices of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), a UN specialized agency.

After close negotiations between the United States and China, as well as extensive multilateral negotiations among other ICAO member states, an agreement was reached on 6 October 2016. The ICAO “Carbon Offset and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA)” resolution committed countries to cap aviation emissions at 2020 levels by 2027. These targets were voluntary until 2027. However, countries were encouraged to opt in prior to that date. As of 12 October 2016, some 66 states, representing more than 86.5 percent of international aviation activity, have stated their intention to voluntarily participate in CORSIA (ICAO 2016).

During the Trump Administration, the US-China Joint Commission on Commerce and Trade (JCCT), was restructured to de-emphasize energy and climate cooperation. The new framework for high-level negotiations, the “U.S.-China Comprehensive Dialogue,” comprised four main tracks: diplomacy and security, economics, law enforcement and cybersecurity, and society and culture (JCCT 2017).

Despite this slow down, China had become a strategic partner of the United States in policy discussions concerning climate change and clean energy. This role has gained particular importance since thousands of people from both countries started working together by collaborating in research, sharing experience, and by developing commercial ventures in deploying clean energy technology. Moreover, the two countries, through their Strategic and Economic Dialogue (S&ED), had begun to discuss periodically politically sensitive issues, trade barriers, and matters related to international security to ensure an open channel for diffusing potential conflict. The postponed meeting of the US envoy with his high-level counterpartsultimately in China and the latest bilateral meeting between the two in MSC are an example of how efforts for dialogue could continue.

In January 2021, as the US prepared to transition from the Trump to the Biden presidency, in addition to managing a global pandemic, the list of responsibilities for economic stability, nonproliferation, counterterrorism, and prevention of large-scale violent conflict and mounting challenges to human security at home and abroad were included in the mounting challenges facing the new Administration. Given the divided political powers at home, the new Administration had to take note of the growing sentiment at home to be prepared and try to prevail in the looming competition with an increasingly powerful rival namely China. In addition, facing a changing international order, the United States needed more allies, partners, and friends as it wrestled with more capable and numerous rivals, mounting challenges to human security at home and abroad.

President Biden was fully aware of the fact that the US global leadership had been insufficient during the preceding four years. Too often, it had relied on an empty chair or hollow words when key interests were at stake. In the meantime, close U.S. allies – such as Japan in Asia and Germany in Europe – had stepped into more active roles. More so, this space was also filled by Russia and, especially, China, whose ascendancy was considered the most significant challenge to the United States.

These new tendencies should by no means overshadow the greatest threats to the US and global security namely, global climate change. Addressing this unilaterally would be extremely difficult.

As it has become clear, geopolitics in the coming decades will be substantially defined by economic and technological competition. Those countries that lead in emerging technologies and shape technical standards will enjoy returns that extend into strategic advantage. Economic, technological, information, human security, and military power now intersect to define many challenges our world faces. Any rapid change in the structure of the global power for now would not be just a simple change of leadership, but it would bring about a fundamental change in the whole structure of the world’s economic and political order.

Whether China-sponsored organizations such as the BRICS (an alliance between India, Russia, China and Brazil), the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Belt and Road Initiative could be considered challenges to the current global order may be too early to say (China and Freeman 2016; 2020). Lately, Indian neutrality to the Russian-Ukrainian conflict compounded by the position taken by Brazil at the Munich Security Conference may be the latest indications of the global South tendencies to a divided world.

Considering prevailing circumstances, to succeed, the competitors to the United States must adapt its alliance system to a world that is more multipolar, more interconnected, and less manageable through siloed frameworks. Such alliances are freely chosen where and with whom to align and at what time with no guarantees of stability. One can argue that for now, at least, the basic pillars of the global order, subject to accepting that sovereignty and economic liberalism remain important features of the multilateral schemes. Although there is no assurance that a more multifaceted order could be developed, based on complex and polycentric governance arrangements among a wider community of national governments, trans-governmental networks, NGO coalitions, multi-national corporations, international organizations and non-state actors – if and when all conditions are present.

Today, while there are ever clearly visible trends towards a new world order, such an order will most probably be a world without a hegemon and with some centers of power and influence.

This growingcomplexity presents significant challenges of coordination. It does not, however, fundamentally contest foundational principles of sovereign equality, economic openness, and rules-based multilateral interactions. The flexibility of partnerships within the world system framework will probably increase for some time, but some of the emerging alliances and coalitions may well turn chimeric, ephemeral, or fantastic.

Given the formidable obstacles facing the humanity, the best way to meet today’s challenges is to reinvest in a U.S.-China partnership across all sectors, that involve all stakeholders, upholding globalization and shaping a new mechanism for cooperative action on relevant twenty-first century issues. Bilateral engagement between the United States and China on climate change have allowed the two countries to leverage their size and significance to mobilize action from other countries, thereby helping both countries achieving several multilateral outcomes in which they have a stake.

Efforts should also be made to leverage the role of non-state stakeholders with concrete tools and capabilities to develop new initiatives in a multipolar word. It is our assumption that humanity will have rather good chances to rely on continued processes of multilateral globalization as the foundation of any sound global new and future world order.

Topical News See more