Mehri Madarshahi: An Open and Competitive Economy – America’s Promise for a Broad and Sustainable Prosperity

August 26 , 2022By Mehri Madarshahi, CCG nonresident senior fellow

The slogan of “Common Prosperity” as a defining theme of Chinese politics today, was introduced by Chinese President Xi Jinping at the beginning of 2021. The program set priorities for economic, environmental, and social policy, at both the national and local levels in China. Despite the central importance of common prosperity in Chinese policy-making, clarity on the concept remains limited outside of the country. This raises questions on what exactly does the term “common prosperity” mean in practice for countries with diverse populations and different systems where the central government is subjected to change every few years and where, as a result, different policies and programs may prevail in relation to common prosperity at the national and local levels. An example in mind is the democratic electoral systems of the United States of America where the federal government has little opportunity to centrally define, determine and implement a resemblance of prosperity programs for the nation.

The Presidential Act of 9 July 2021 (Executive Order), followed by three other Acts approved this year, are the closest document which define paths to common prosperity in the United States. They aim at promoting a fair, open, and competitive marketplace as a cornerstone of the American economy for its workers, businesses, and consumers. They lay the ground for American promise of a broad and sustained prosperity by creating more high-quality jobs and the economic freedom to switch jobs or negotiate a higher wage. For small businesses and farmers, it creates more choices among suppliers and major buyers, leading to more take-home income, which they can reinvest in their enterprises. For entrepreneurs, it provides space to experiment, innovate, and pursue the new ideas that for centuries have powered the American economy and improved American quality of life. For consumers, it means more choices, better service, and lower prices.

In the past, Federal Government inaction has contributed often to problems with workers, farmers, small businesses, and consumers making such prosperity programs an illusion. Chief among these are the prevailing consolidations of industries which inevitably led to a weakening of competition in markets and a widening of racial, income, and wealth inequality. These trends have also contributed to deregulation of financial innovations and increases in capital gains for some, as well as a downward pressure on wages.

Though wealth inequality has grown in other industrialized democracies too, the U.S. figures mark this country as an outlier. A 2018 review by OECD (SDD/DOC(2018) of EU countries shows that, on average, the top 10 percent of households own 52 percent of wealth, while the bottom 60 percent own 12 percent. According to the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System in the United States the combined wealth of all households amounted to US$129.5 trillion in the first quarter of 2022. The wealthiest one percent held 32.1 percent of the total wealth, up from 23.4 percent in 1989.

The top 10 percent of households owned US$70 of every US$100 of wealth (up from US$61 in 1989) while the bottom half, whose share never exceeded 5 percent, now holds just 2 percent of household wealth in the United States.

Since 1960, the relationship between race, ethnicity, and inequality have been well-documented. During this period, the median wealth of white households has tripled while the wealth of Black households has barely increased. For decades, the unemployment rate among Black Americans has been roughly twice that of white Americans.

Black Americans unemployment has been roughly twice that of white Americans. According to Chetty’s research, black Americans are also underrepresented in high-paying professions. As of 2020, only four CEOs of Fortune 500 companies were Black. Black and American Indian children have far lower economic mobility compared to white, Asian, and children of Hispanic ethnicity,. Though racial discrimination in housing was banned by the Fair Housing Act of 1968, the effects persist.

The COVID-19 pandemic laid bare many of these disparities. American Indian, Black, and Latino Americans were more hospitalized with and died from COVID-19 than white Americans—an inequity that Catherine Powell calls the “color of COVID.” People of color were more laid off; and they were more likely to be considered essential workers, performing jobs that typically came with greater exposure to the virus, such as cashiering and package delivery.

This uneven distribution of wealth has so far not led to any major social and political unrest and as Thomas Gilovich suggests “indifference lies in a distinctly American cultural optimism. At the core of the American Dream is the belief that anyone who works hard can move up economically regardless of his or her social circumstances”. According to Pew Research, most Americans believe the economic system unfairly favors the wealthy, but 60% believe that most people can make it if they are willing to work hard. Senator Marco Rubio said that America has “never been a nation of haves and have-nots. We are a nation of haves and soon-to-haves, of people who have made it and people who will make it.”

This unique brand of optimism prevents American from demanding or making any real changes. And according to Nicholas Fitz (31 March 2015) “the problem is the great divide between our beliefs, our ideals, and reality”.

By all accounts, and despite all, the current U.S. wealth gap is far larger than needed to reward initiative or to sustain rapid economic growth. Over the past three decades, economic growth rates have slowed even as more and more wealth has been concentrated at the top.

EDUCATION

Since 1989, human capital development in the form of training and education shows that 7 out of 10 Americans among the wealthiest 10 percent have at least a bachelor’s degree. This ratio shrinks to only 1 out of 5 members among the least wealthy half of all Americans.

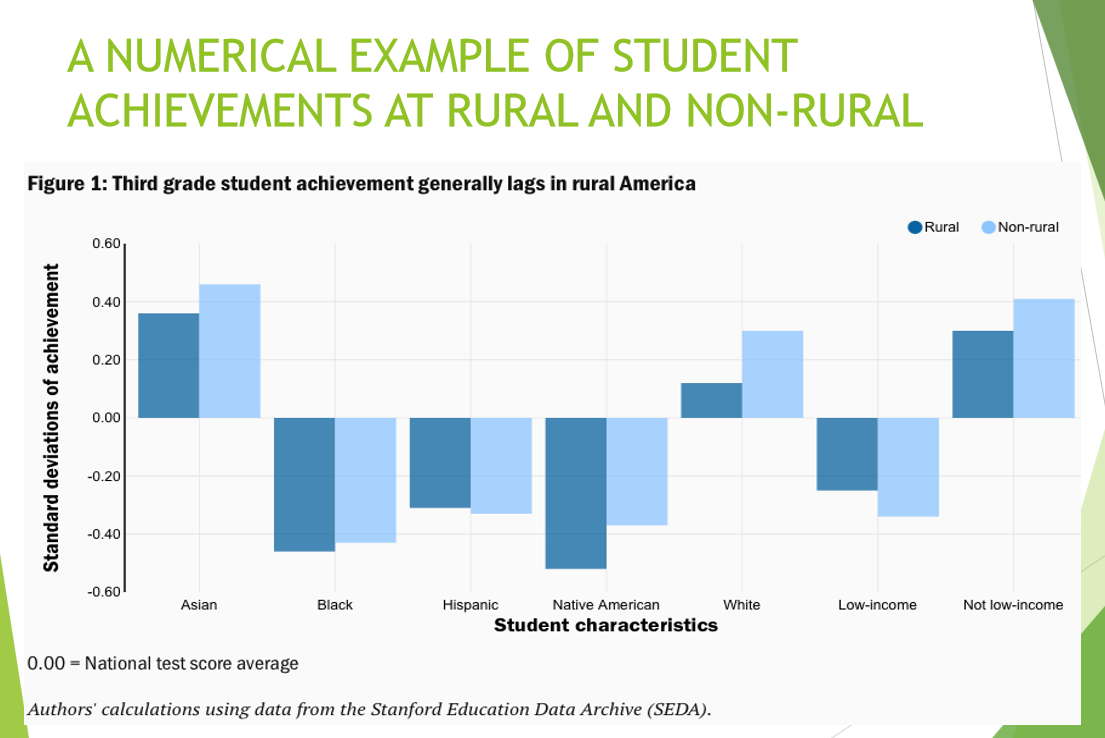

Rural youth collectively comprise 20 percent of public-school students in the United States. Understanding the status of their educational opportunity is, therefore. important.

In recent decades, the hollowing out of Rust Belt towns, a devastating opioid crisis, and bitterly divisive national politics have called attention to the challenges of growing up in rural America. Despite enhanced focus on these communities, educational opportunities in rural areas are less clearly understood than in non-rural areas, owing in part to the fact that rural education nationwide has been an empirical challenge. Many rural school districts are small, and most state achievement tests are not comparable across state lines. Nonetheless, in some rural districts, poor and nonpoor students are experiencing similar levels of educational opportunity, whereas in other rural districts, poor and nonpoor students see pronounced stratifications. With respect to test score differences. geographic isolation appears to have a negative association with achievement beyond what can be attributed to differences in a community’s socio-economic status or racial/ethnic composition. Differences in achievement for rural and nonrural Native American students are nearly as large (0.15 standard deviation).

How can we ensure that today’s low-skilled service workers, who are disproportionately Black, Hispanic, and Native American, are included in the higher-quality pipelines of tech-oriented and high- skilled service jobs? Equipping minorities with the appropriate balance of future- oriented skills is integral for solving the challenge of underrepresentation. This would create space for minorities.

Minority communities have borne the brunt of the pandemic’s deleterious impacts. Their unemployment rates rose faster than white unemployment rates and remain elevated. Without policy interventions, startup job creation in majority-Black and Hispanic communities will skew toward lower quality and reinforce inequality.

In this regard, there are three questions regarding the job market to focus on. How can policymakers anticipate and plan for employment demand as technology-enabled growth increases? What do the changes in employers’ needs mean for the inclusion of historically underrepresented groups in the transforming workforce? And how do policymakers actively close equity gaps for underrepresented minorities?

Employers are keenly interested in a three-dimensional skill portfolio and workers endowed with high-quality tech-specific skills are rewarded with income premiums. Not surprising, Black, Hispanic, and Native American individuals are acutely absent from strategic opportunity. Creating access to such opportunities requires policy attention that links targeted changes in environment where underrepresented populations live, work, and go to school.

The COVID crisis has accelerated a tremendous loss in productive capacity among non-white and Hispanic communities. The pandemic forced 10 million workers into joblessness and accelerated the financial ruin of roughly 100,000 small businesses.

It is not a secret that a more efficient and equitable strategy could promote equitable distribution of homeownership, retirement savings and higher education through tax credits instead of tax deductions and/or direct cash support. Subsidising loans and targeting them to those of modest existing wealth could also help alleviate some of the existing problems with poverty in America.

The Chinese government has policies and measures in the pipeline to improve the wealth distribution system and narrow the income gap between different regions and groups. The measures for common prosperity are comprehensive and consistent with previous policies and five-year plans and with the traditions and practices of the CPC.

In “A Better Life for All Our People,” Chinese President Xi Jinping stressed that a key aspect of modernization is “improving the quality and efficiency of development to better meet the growing expectation of our people in all areas, and further promote well-rounded personal development and common prosperity for all.” In other words, the community and the individual are part of the balance.

Alleviation of poverty or equitable income distributions

After nearly a quarter century of steady global declines in extreme poverty to historically unprecedented levels, there has been a sudden reversal. This setback stems overwhelmingly from the effects of a pandemic (COVID-19) and its subsequent global economic crisis. However, in some places the reversal is being accentuated by violent conflict and climate change, slowly accelerating risk that is already driving millions into poverty.

While important gains in reducing global poverty have been made steadily it was also increasingly unrealistic to expect that the goal of reducing extreme poverty to below 3 percent by 2030 could be reached. Unprecedented levels of global prosperity today are threatened by three global forces that are intertwined and reinforce one another: a pandemic; armed conflict; and climate change.

The effects of COVID-19 – as well as climate change and violent conflict – fall hardest on the poor, less because of their exposure to such risks than because of their high vulnerability. Poor people’s vulnerability reflects a lack of access to institutional resilience mechanisms (such as social protection, insurance, and credit), and reliance on low-quality public services, among other factors. (Brown, Ravallion, and van de Walle 2020).

President Joe Biden has pledged to reduce economic inequality leading to poverty with new social spending financed by higher taxes on the wealthy and corporations. In his efforts to meet these pledges he faced opposition from those who say his plans do not go far enough opposed to those who claim his plan goes too far.

This political infight has given reason to influential entrepreneurs, such as Ray Dalio, to state that, “The US is not able to solve the gap between the rich and poor and achieve “common prosperity.” He believes that US administrative authorities have limited power in wealth distribution. Taxes play an important role in reforming the distribution system. But it is the US Congress, not the US president, that regulates taxes. Against the backdrop of partisan struggles, it is almost impossible to solve the rich-poor gap. Any measures that tend to make an improvement pushed forward by Democrats could hardly be supported by the Republicans”. Democrats generally subscribe to higher income taxes for rich and Republicans argue that higher taxes would stifle economic growth and innovation.

Achieving common prosperity – A FEW STEPS IN A RIGHT DIRECTIONS

A)American Rescue Plan

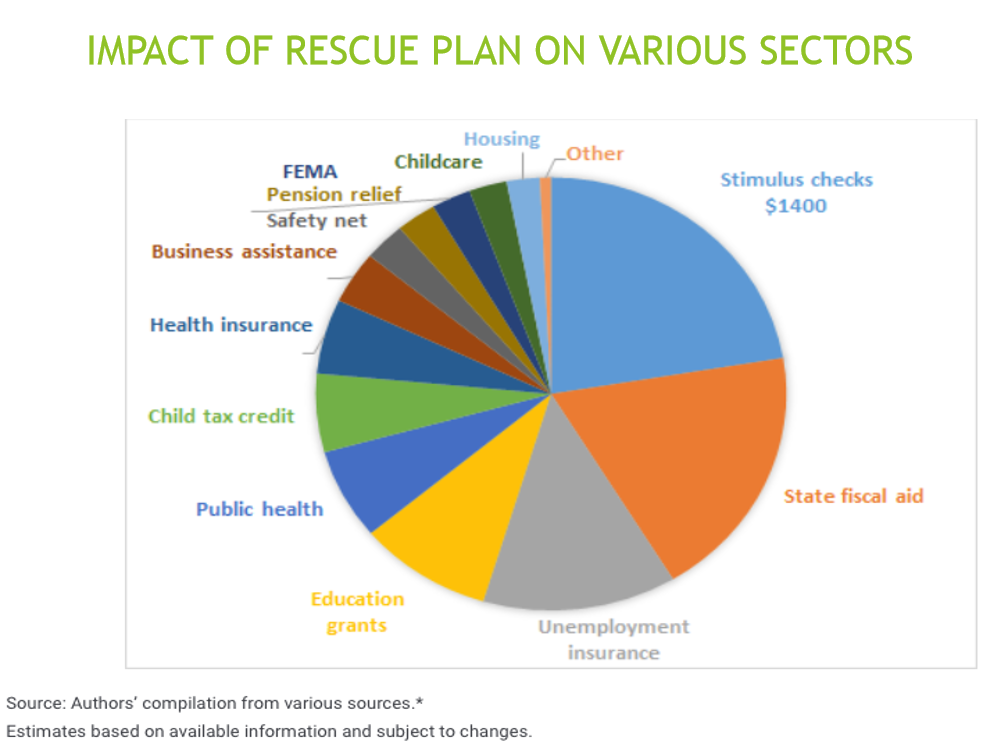

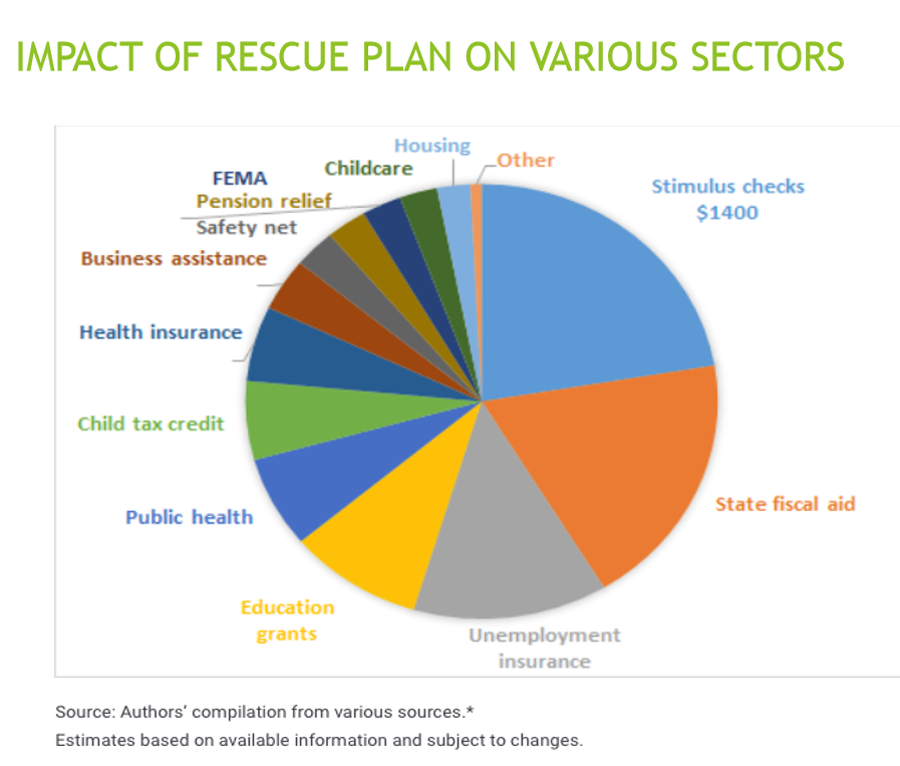

Building Back minority communities requires concomitant action from labor market investments and policy interventions to strengthen these communities’ capacity to cultivate startup growth .The recent US$1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan Emergency Legislative Package aimed at funding Vaccinations, provide Immediate, direct relief to families bearing the brunt of the COVID-19 Crisis, and support Struggling Communities during economic downturn. The Plan was approved by Congress in Jan 2021. Through it, President Biden laid out the first step of an aggressive, two-step plan for rescue, from the depths of this crisis, and recovery, by investing in America, creating millions of additional good-paying jobs, combatting the climate crisis, advancing racial equity, and building back better than before. The American Rescue Plan was to change the course of the pandemic, build a bridge towards economic recovery, and invest in racial justice and intergenerational inequities that was becoming worsened in the wake of COVID-19. Researchers at Columbia University estimated that these proposals also will cut child poverty in half.

B- US Chip and Science Act

Considering America’s shortage of skills, know-how and productive capacity in the supply chains, the Congress approved ,on a bipartisan basis, a new plan named the US Chip and Science Act. The chips legislation is to provide US$52bn in subsidies for US chip manufacturers and more than US$100bn in technology and science investments, including the creation of regional innovation hubs and expanding the work of the National Science Foundation in the immediate future.

Biden praised the Chips and Science Act, saying it would lower “prices on everything from cars to dishwashers”. He said the legislation would also create new jobs and ensure “more resilient American supply chains, so we are never so reliant on foreign producers for the critical technologies”.

C) The Inflation Reduction Act (The climate, tax and drug bill)

As millions of Americans suffered through record heatwaves and devastating floods this summer, Congress finally responded to the climate crisis with a major investment. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) is the most significant federal climate legislation with no parallel in US history. It is to provide US$370 billion over 10 years to support clean electricity, electric vehicles, heat pumps and more.

The Act is mainly a climate investment and its spending package aims at turbocharging the largest economy’s belated shift to clean energy.

It also includes measures allowing to negotiate lower prices for prescription drugs, introduce a minimum 15 per cent tax on large corporations, and a new 1 per cent tax on share buybacks.

In a statement, Biden said the bill would “make government work for working families again” by lowering the cost of prescription drugs, health insurance and everyday energy costs while reducing the federal deficit.

Of course, there is a chasm between the law on paper and how the provisions in its 700-plus pages are implemented in coming years. Among them are tangible health benefits like lower rates of respiratory illness as a likely outcome of this Plan, by 2030.

Other details in the IRA include:

1-The electrification of highly polluting heavy trucks that service ports and sprawling logistics centers – typically located in low-income communities of color.

2-A US$7,500 credit for clean vehicles or half of it, if key battery materials are mined in a country that the US has a free-trade agreement with or if they have been recycled in a North American facility.

3-Energy upgrades for 20 to 50 million American buildings not upgraded in the past 40 years with natural gas, coal and oil to clean electricity.

4-$2.6 billion for coastal resilience through emissions-cutting actions may result in a slowdown in sea-level rise. That could end up delivering a lifeline to vulnerable coastal communities.

IRA had also some controversial weeteners for the oil and gas industries. The reason for which enthusiasm from Big Oil is not shared by some smaller and independent producers, or those who pump most of the crude and gas productions in the US. They are bracing for a raft of new fees and taxes, including penalties on leaking methane and much higher payments for drilling on federal land. The clash over this landmark piece of legislation underscores longstanding tensions between large, public oil companies and their smaller rivals when it comes to federal policy on climate change. The smaller companies account for 83 per cent of America’s oil production and 90% of natural gas and natural gas liquids. By providing hefty tax credits for carbon capture, hydrogen and biofuels, the bill will help underwrite supermajors’ green transition strategies at a time when they’re under intense pressure to accelerate investments in clean energy. Smaller oil producers that don’t have refining arms or renewable investments are more exposed to provisions that take aim at fossil fuels.

An examination of Environmental Protection Agency data reveals also another pitfalls of such approach: companies have broad leeway to decide how much pollution they report, based on how they interpret more than 100 pages of complex agency rules.

Nevertheless, according to researchers, the bill can help to:

-Save the average household US$500 a year on energy bills.

-Create more than 9 million jobs — an average of almost 1 million jobs sustained over the next decade.

-Target investments to reduce pollution in overburdened communities, including cleaning up ports and schools, and funding community-led clean energy projects.

-Prevent 4,000 premature deaths annually due to reduced air pollution;

-Make energy-saving technologies more affordable and provide tax credits for used electric vehicles, for heat pumps, for home electrical upgrades, and a 30% tax credit for residential solar.

In March 2022, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) unveiled a draft rule requiring publicly traded companies to disclose climate-related risks and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The draft rule is based on the globally accepted framework of the Task Force on Climate Related Disclosure (TCFD). If fully implemented, the SEC rule would help investors, companies and others manage growing financial risks linked to GHG emissions and shift investment toward businesses advancing climate solutions. These shifts could help nudge the country closer to its 50-52% emissions-reduction target.

Despite its big and/or small pitfalls, the bill makes possible – a roughly 40% drop in emissions by the decade’s end. It equals reductions of a nearly a gigaton, or one billion tons, of annual carbon dioxide emissions by 2030. That’s the equivalent of France and Germany’s combined annual emissions.

And politically it gets the US sufficiently down the road, so that better government policy can follow later this decade.

On another issue,..

North American economic integration has also encouraged a steady increase in investment among all three countries. Given geographic proximity, Mexico, Canada and the US face common issues relating to environmental sustainability, natural disasters and pandemics.

Close collaboration between the 3 countries is critical to addressing broader economic, security and environmental challenges. This collaboration rests on shared democratic values, respect for the rule of law and free market principles. They collaborate within the Organization of American States, at the Summit of the Americas and at the G20, with the aim of strengthening the effectiveness of these international bodies to address pressing global challenges.

Topical News See more