Jörg Wuttke: A Roadmap to Bolstering EU-China Relations

“European multinational companies (MNCs) in China are not making plans based on the next one or two years—they are looking to the next one or two decades. While there is no sign of “decoupling” between Europe and China, there is a growing political story to be told and business is becoming increasingly politicized. China’s economic rise follows historical norms, the way that the EU interacts with China in business should emphasizes existing institutions and WTO reform, ultimately producing an environment in which European business acts as a transition catalyst in China.”

——Jörg Wuttke , President of the EU Chamber of Commerce in China.

International coverage of China in 2020 was dominated by two stories: the COVID-19 outbreak and the resulting economic challenges, which have left companies navigating in the dark, and created the potential for various markets to decouple from China. While the former was all too real, the latter is a far less straight-forward story. In the areas where European Chamber members are able to participate in China’s economy, they report no significant change in plans to redirect current or planned investments elsewhere. Findings from the European Chamber’s Business Confidence Survey 2020 (BCS 2020) indicate that only 11% of member companies were considering doing so last year, which is towards the lower end of the norm for the last decade.

Even taking into account the potential economic upheavals that could follow the COVID-19 crisis, European multinational companies (MNCs) in China are not making plans based on the next one or two years—they are looking to the next one or two decades. Their small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) partners remain similarly committed to serving the market here, as do the European SMEs that target Chinese customers directly.

However, there is certainly now the potential that the economic impact of COVID-19 will result in increased diversification of certain supply chains. Many companies are naturally seeking to build resiliency after suffering supply shortages since China was the first market to be flattened by the pandemic. However, this should not be misunderstood as “leaving.” Instead, it is likely to mean less new investment into China as resources are spent elsewhere.

Discussions on this topic with various business leaders reveal some clear trends. European MNCs’ increasing investment are looking to onshore their supply chains into China and deepen their local production capacity to insulate themselves from further disruptions. Of those that have left or are planning to leave, most were in China for export markets rather than for local consumers.

1 No Major Economic Decoupling Yet, But a Growing Political Story

While there are currently no economic factors strong enough in and of themselves to drive European investors out of China, business decisions are not made in a vacuum. Political voices calling for a tougher stance on China are building into a chorus across the world. The only thing Americans seem to agree on these days is that the United States must embark upon a new era of relations with China, and abandon the engagement-at-all-costs approach that defined previous administrations in favor of something considerably more hawkish.

When former EU President Jean-Claude Juncker delivered his 2017 State of the European Union speech, he spoke of the need for the EU to strengthen its trade agenda. “Yes, Europe is open for business,” he said, “But there must be reciprocity. We have to get what we give.” This signaled something of a departure from the more conciliatory approach that Europe had previously taken in its dealings with China. Since then, Europe’s tone has continued to evolve in response to China’s slow-moving economic reform agenda and what many view as an increasingly aggressive stance coming from Beijing. The EU’s approach hardened further in a strategic communication released in 2019, which labeled China an “economic competitor” and a “systemic rival.” A toolbox is now under development, including an investment screening mechanism, to better protect the EU common market from outside distortions.

1.1 Several Months of Increasing Tensions

While China and Europe regularly experience friction outside the economic realm, the last couple of years have yielded an astonishing number of issues that have raised concerns and increased risk for businesses. These include the political ramifications of the National Security Law aimed at Hong Kong, the extensive allegations of forced labor and internment of ethnic and religious minorities in Xinjiang, the insertion of the Communist Party of China (CCP) into every aspect of civil society and even business, and the politicized nature of the narrative around the early days of the COVID-19 outbreak. One of these on their own would present a serious point of contention between the political leaders of Europe and China. Together, they risk creating a long-term, downward spiral, as evidenced by the measures already applied by the United States in response to developments in Hong Kong and the Xinjiang, which have the potential to seriously impact European companies.

1.2 The Politicization of Business

In the Chamber’s BCS 2020, 43% of members reported that the business environment had become increasingly politicized over the previous year, compared to just 10% that felt it was less so. Members identified the Chinese Government and Chinese media as the most likely sources to increase political pressure on businesses.

European companies in China can predict economic trends, shifting consumer tastes and the supply and demand of inputs, but they cannot predict ever-shifting political demands. Regardless of the areas where progress has been made in China’s business environment over the past year, companies now have the added concern that arbitrary punishment may be handed down to them due to the actions of their home-country governments.

For example, the 2020 conclusion of the EU-China Agreement on Geographical Indications (GIs) will help to protect the quality of 100 different European and Chinese food and beverage products, and increase consumer confidence. However, there is now a risk that producers and importers of these newly protected items may suddenly face disruptions if they become the focus of Chinese retaliation in response to political issues.

2 China’s Economic Rise Follows Historical Norms

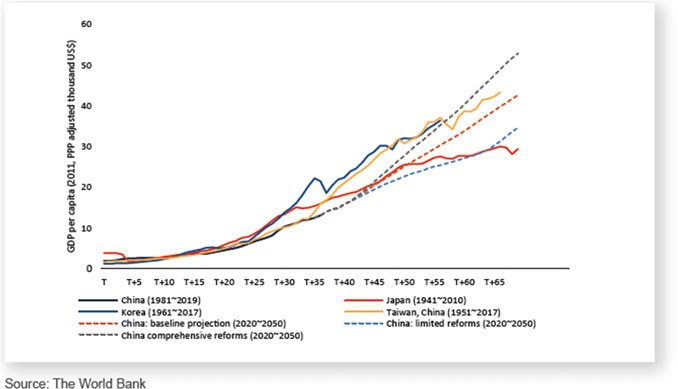

China has become a pivotal market for European players over its four decades of economic opening, and it has the potential to follow the trends of other economic miracles predating its own. Although it is commonly stated in China that its rapid rise over the last 40 years is somehow unique, the European business community sees it as yet another example of how economies bloom when modernization is prioritized and their development is predicated on market opening.

Mass and rapid industrialization and modernization have been experienced by multiple economies throughout the last 150 years. China is following a path similar to the “Four Asian Tigers” of South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore. These markets transitioned from largely undeveloped economic systems/trading ports to highly developed, competitive centers for industry, innovation and finance, all over the course of around four decades.

Larger economies have historically done the same. Like many countries during the second industrial revolution at the end of the nineteenth century, Germany, shortly after its unification in 1871, rapidly industrialized. An even more dramatic process of modernization emerged over a similar period of time when Meiji Japan went from a feudal, chiefly agrarian economy to an economic force on par with the strongest nations of the day. So long-lasting were the lessons of those experiences that even after the heavy bombing sustained by both countries during the Second World War, they were able to rebuild themselves into the powerhouses that they became just a few decades later.

The European business community views China no differently than these earlier examples. The Chinese economy has followed similar growth trends over comparable timelines, as demonstrated in the World Bank chart, which shows GDP per capita in PPP terms since the introduction of the market reforms in respective markets. European companies are ready to play a key role in the development of yet another economic powerhouse in East Asia.

3 In China for China, and the World

European companies derive far more from being in third markets than just the immediate benefit of increased sales. They also benefit from the global nature of the talent they acquire, increased competition and their exposure to new forms of innovation. China is no different in this respect.

The success of many of Europe’s best companies comes from decades of competing with peers at home and abroad. The formation of the European common market paid immediate dividends as companies previously protected by borders and tariffs were suddenly forced to cut the fat or fall behind. The winners of that race then entered international markets as globalization took off and the World Trade Organization (WTO) gave them access to other fields of competition, while also keeping them on their toes as their home markets welcomed new entrants.

With China remaining only partially open, and with a level playing field only reported by half of European companies operating here, the resulting loss of competition for both European players and China’s own champions is a grievous one.

The foreign companies that used to have their pick of China’s best and brightest now face strong competition from local companies, further underlining how necessary it is to have a presence here, as well as to be able to easily assign talent from other parts of the world to China operations. European companies are keen to send their global talent into China for them to foster new skills and gain experience that can be applied elsewhere. It also helps companies unlock synergies by bringing the best local and foreign talent together. Unfortunately, China is far more restrictive to foreign talent than the EU’s various member states.

In the interests of creating a more competitive business environment, an important part of China’s ongoing opening-up and development must therefore include reducing the restrictions currently placed on foreign talent, bringing it more in line with the EU.

4 China’s Market Access Lags Behind Its Market Potential

For many years, the European Chamber has advocated for more complete opening in China, and equal treatment for foreign enterprises. The current web of restrictions facing foreign companies trying to invest in China are extremely burdensome and actually hold back China’s overall development. It will be only possible to unleash the full potential of the market by increasing foreign investment, which in turn will also strengthen competition.

Foreign companies that want to invest must first navigate the Foreign Investment Negative List (FINL), a table of different industries in which foreign investment is either forbidden or accompanied by conditions for entry. Restrictions include, for example, equity caps or requirements that the Chinese partner must have majority control in a joint venture (JV).

The list underwent a revision in late June 2020, with seven items being removed, leaving 33 restricted/prohibited sectors. Most of the removed items are of limited significance, such as seed development, nuclear fuel and nuclear radiation processing, oil and gas exploration, and pipe network facilities. However, the remaining items are composed of sectors across a broad spectrum of interest—traditional Chinese medicine production is not exactly a priority for European business, but legal and telecommunications services certainly are.

In addition to the FINL, foreign investors must also navigate the less frequently discussed Market Access Negative List (MANL). This list affects all market players, not just foreign ones, which serves as a reminder that China’s private companies are also subject to the onerous regulatory framework here. While the MANL has 130 broadly defined items—which translate into restrictions on the provision of hundreds of different goods and services—the vast bulk of these are not prohibited, but instead require various permissions.

European business leaders report being twice as likely to face such indirect barriers compared to direct ones. Foreign banks, for example, were finally able to enter without JV requirements as of just a couple of years ago. However, once allowed in they found a fully saturated market, in which only a few niche opportunities in areas like cross-border services held meaningful potential. Furthermore, the requirements for obtaining an operating license remain considerably outside of international norms. To date, only a handful of foreign banks have been successful, though recent announcements by the China Securities Regulatory Commission could signal that things are moving in the right direction.

Insurers, which have just seen their industry removed from the most recent FINL, face different, but no less burdensome, bureaucratic barriers to full entry. To offer their services nationwide, they must apply for a separate license in each individual province, with only one application being accepted and processed at a time. With the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission issuing those licenses at a pace of about one a year, this means that any foreign insurance providers wanting to offer services in even just one-third of the country would need a decade to acquire them, assuming that they were all smoothly approved. Meanwhile, lying in wait for them are China’s biggest insurers, which have been able to easily secure their positions across the country relatively unimpeded.

In information, communication and technology, there are rapidly emerging sectors with plenty of market share up for grabs. Unfortunately, most telecommunications infrastructure providers are increasingly squeezed out of procurement as China fights to support its national champions, and licenses for value-added telecoms—including cloud and virtual private network services—remain largely out of reach to foreign companies. At the same time, digital solutions developed elsewhere by European firms have to deal with the Great Firewall and its seemingly ever-growing list of blocked sites.

In addition to the removal of certain items, the revised FINL also now includes a provision that gives the State Council the power to supersede the restrictions on the list for any company that it selects. It seems likely that this is meant to allow the State Council to “pilot” opening in certain sectors after the previous piloting model, through China’s free-trade zones, failed to deliver any meaningful results.

This could be good news for foreign companies that the State Council gives the green light to. However, it also raises concerns within the European business community with respect to China’s increasingly politicized business environment, as outlined previously. It is not beyond the realm of possibility that a company that gains favor one year, may suddenly fall out of favor the next if its home-country government comments on an issue that is deemed to be sensitive.

4.1 Procurement Blues

For many that have successfully navigated China’s entry requirements, they face further limitations in a public procurement market that remains largely closed to foreign players, with “regulations and policies favoring domestic over foreign goods and services.” In terms of inputs, European companies have identified some opportunities, but only to play niche roles and mostly in areas where they have a certain technology that local competition cannot replicate.

Service providers are similarly marginalized. For example, construction service providers (CSPs), long limited to only a handful of potential projects, remain tiny players within the technically open market. With only four possible types of projects open to foreign CSPs, it is not surprising that their market share is less than 2%. The only option they have is to play a “consulting” role in which they do the work for a domestic CSP and receive only part of the revenue and limited recognition.

5 Rhetorically? Things Couldn’t Be Better

On paper, it appears that China is opening up its economy and moving in the right direction. In recent years, the Chinese Government has continuously reiterated this narrative. The ambitious statements in President Xi’s first Davos address in 2017 offered hope for a brighter future when he said that “pursuing protectionism is like locking oneself in a dark room,” and that no one would emerge as a winner from a potential trade war. Plans for increased opening up the economy to foreign investment seemed a foregone conclusion at that point in time.

These plans were formalized through the State Council’s Notice on Several Measures on Promoting Further Openness and Active Utilization of Foreign Investment (State Council Document No. 5 or Guofa [2017] No. 5), released in January 2017, and the Several Measures for Promoting Foreign Investment Growth (State Council Document No. 39 or Guofa [2017] No. 39), released in August 2017. An additional positive shift in China’s management of foreign investment was expected with the 2019 adoption of the Foreign Investment Law (FIL), which came into effect on January 1, 2020. All of these had the intention of streamlining existing regulations for foreign businesses and stimulating foreign investment.

In reality, the results have lagged far behind the promises. As recognized in the European Chamber’s 2018 report 18 Months Since Davos, which analyses China’s reform progress in the 18 months that followed President Xi’s 2017 Davos address, there was some indication that the pace of reform had increased. However, the actual reforms resulting from the two State Council documents were found to be “still insufficient and incomplete.” Although the report identified some small market openings that had taken place, as well as improvements in the R&D environment and more stringent enforcement of environmental regulations, it also found serious issues remaining in China’s economy, including SOE domination, unfair technology transfers and a burdensome regulatory environment, among others. These conclusions are still accurate nearly three years since this report was published.

A recent World Bank study pinpoints a combination of macro-economic forces and policy choices that have limited China’s development and resulted in untapped potential. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, China’s productivity in diverse sectors was a major contributor to decades-long, double-digit economic growth. However, the choice not to reallocate resources from sectors with traditionally low productivity, such as agriculture, towards more productive industries and services—as well as from inefficient SOEs to private firms—has resulted in a steady drop in productivity since 2007.

Even though weaker growth was undoubtedly exacerbated by the financial crisis, the World Bank study highlights that the lack of efficiency within SOEs, and the fact that they still lag far behind private enterprises in terms of efficiency, has also played a role in this. While China’s growth potential still remains, its per capita income and productivity are far below advanced economies. In order to close this gap, China will need to allocate more resources to the private sector, invest more in human capital, and upgrade industrial processes and management practices.

6 Policy Miscalculations

There are host of other factors limiting market potential and preventing meaningful opening in China. Political and economic mismanagement—as well as the increased incidences of aggressive diplomacy and a tendency to define its own forms of multilateral engagement—has seen China’s international image slowly deteriorate. At the same time, a failure to establish transparent, effective and impartial institutions, and a loss of talent from within its bureaucracy, raises questions over China’s actual capacity to implement the changes needed to establish a fair, open and competitive business environment.

6.1 Sustainable Development Requires Sound Institutions

When businesses are looking to make long-term investments, they require a high degree of certainty that solid institutions provide. If a country fails to create a sound institutional and economic framework, it will struggle to sustain its development. The resulting lack of transparency, consistency and predictability in legal and administrative processes erodes trust and can ultimately cause long-term damage to economies.

China’s opening up measures have in some cases been highly promising. The removal of certain industries from the negative list has, in theory, paved the way for investments in previously off-limits sectors of the economy. However, as previously mentioned, a host of indirect barriers prevent many companies from actually being able to fully contribute to China’s development.

This approach to managing foreign investment provides no real transparency or legal certainty, and therefore makes China’s market less attractive, particularly in the current climate in which companies are becoming more and more risk-averse. Increasing predictability—by creating reliable mechanisms for granting licenses and approvals based on transparent and measurable factors—would not only boost business confidence, but also raise the credibility of China’s government.

The need for institution building is recognized by many in China. For example, it was a central recommendation in China 2030, a report jointly produced by the Development Research Council and the World Bank. Chinese and international experts agreed that without strong institutions, China’s development will sputter just at the time that it needs additional forward momentum to escape the middle-income trap.

7 EU Must Prioritize Existing Multilateral Platforms

It is important that the EU continues to work together with China to follow through on pledges to reform the WTO. This is particularly salient given current trends: China has been increasingly engaging with the rest of the world through its own mechanisms, and the continued deterioration of US-China relations is sucking so much oxygen out of the room that there is a real danger that efforts to reform the WTO may be abandoned altogether.

One example of China’s homegrown form of engagement is its preference for its “17+1” initiative, instead of using the already well-established European Union and its various dialogues with neighboring non-member states to reach the same audience. With Europe having long upheld a “One-China” policy, it begs the question of why China does not reciprocate and implement a “One-Europe” policy.

As already alluded to, the BRI provides another example of how China is forging its own ways to engage with the world outside of established global norms. While third countries previously had to rely on existing multilateral organizations to fund major infrastructure projects, through the BRI, China has created the circumstances that see it freely investing in these countries’ strategic infrastructure, under conditions that, on the face of it, appear favorable. At the same time, the BRI is functioning as a platform to steadily introduce “Chinese standards” outside of China, at the expense of globally approved ones. According to the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission’s 2018 Report to Congress, “Chinese companies are seeking to define import and export standards for a broad set of technological applications, which, taken together, could alter the global competitive landscape.”

7.1 EU Poised to Further Protect Against Market Distortions

The continued lack of significant and meaningful opening of China’s market has increased calls within the EU for China to offer reciprocal access to its market. Europe must maintain its open market, but it can no longer afford to continue with a naïve approach in its dealings with Beijing. Instead, the EU looks set to develop and deploy stronger mechanisms—including the investment screening mechanism and the international procurement instrument—to protect its market from non-market distortions, such as investments made with state-backed capital.

The unfortunate conclusion is that former US President Clinton may have been wrong when he asserted in 2000 that China would “import one of democracy’s most cherished values: economic freedom.” Instead, it is looking more likely, at least for the time being, that Western liberal markets will need to become more like China’s in order to protect themselves from the more pernicious aspects of China’s economy.

8 European Business as a Transition Catalyst

European companies are ready to deepen their positions in China given the right opportunities. Ongoing investment in China by Europe’s top companies means more than just numbers on a ledger. The new factories and plants currently being built are cutting edge, and will be among the most modern facilities in the world, integrating emerging technology, like AI, 5G and cloud platforms, to create operations that will set new standards. They will provide well-paid jobs that teach new skills to China’s growing pool of skilled workers, laying the foundation for further industrial upgrading in China through the high-quality inputs they provide and by raising the expectations of Chinese consumers.

The current US administration’s efforts to force decoupling from China could have a serious impact on what technology is allowed to be sold to China. Its push to impose export controls on American semiconductors to key Chinese companies has already exposed the potential economic damage that could be caused in areas where China is far behind, as well as the increased harm this would have on the US-China relationship. Similarly, the United States has the ability to seriously impact China’s best companies by restricting their access to, and ability to complete transactions in, USD, since China’s tight control over its monetary system has left the RMB with only a tiny share of global transactions. However, such measures would likely be used only sparingly and in a highly targeted way by the US Government, if at all.

In areas where China is comparatively strong, efforts to decouple or cut-off access to American technology are likely to have a more muted impact. In some areas of technology, Chinese firms have already surpassed their American competitors. This holds true for China’s internet companies, many of which are world leaders. Coupled with a robust venture capital culture, China can endure and even thrive if deprived of American inputs in these areas.

But Chinese companies are overwhelmingly behind Europe, Japan and the United States in industrial technology. To survive decoupling in this area, China would need to bring other partners closer to compensate. This would be crucial for China to boost its productivity sufficiently to escape not only the middle-income trap but also the demographic cataclysm that could result from its rapidly aging population.

European and Chinese technological edges are complementary, and they could together endure in a world undergoing deglobalization. If this is to stand a chance of happening, China must develop sound institutions to create a transparent, consistent and predictable business environment, eliminate regulatory barriers and offer the EU reciprocal access to its market in a timely manner.

Jörg Wuttke is President of the EU Chamber of Commerce in China, as well as the Vice President and Chief Representative of BASF China. From 2001 to 2004 Mr. Wuttke was the Chairman of the German Chamber of Commerce in China. He is currently President of the EU Chamber of Commerce in China—an office he previously held from 2007 to 2010 and from 2014 to 2017. From 2013 to 2016, and again since 2019 Mr. Wuttke has been Vice Chairman of the CPCIF International Cooperation Committee, a group representing multinational companies in China’s Chemical Association. Mr. Wuttke is a member of the Advisory Board of Germany’s foremost Think Tank on China, MERICS, in Berlin. Mr. Wuttke holds a BA in Business Administration and Economics from Mannheim and studied Chinese in Shanghai in 1982 and Taipei from 1984 to 1985.

// Editor’s note

Transition and Opportunity: Strategies from Business Leaders on Making the Most of China’s Future is the third book in the “China and Globalization” series, published in partnership with Springer Nature. The 22 essays contained in this volume are the work of a wide range of global experts in China’s business community. Contributors include the leaders of international chambers of commerce, CEOs and senior executives from leading MNCs and industry experts or country heads from global consulting firms. In a world of constant change and uncertainty where there is so much in doubt, these perspectives on the future of business in China, which are rooted in real-world experience and proven strategies that work, provide an immense trove of knowledge for those looking make the most of China’s bright future.

Transition and Opportunity

Editors: Huiyao Wang, Lu Miao

Published in February, 2022

Publisher: Springer Nature Publishing Group

Download Book at Springer

https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-981-16-8603-0

Transition and Opportunity: Strategies from Business Leaders on Making the Most of China’s Future is the third volume in CCG’s “China and Globalization” series of books edited by Dr. Huiyao Wang and Dr. Lu Miao.

Series Editors: Huiyao Wang Lu Miao

Publisher: Springer Nature Publishing Group