【Asia Times】Finding paths through a bumpy world

October 12 , 2021

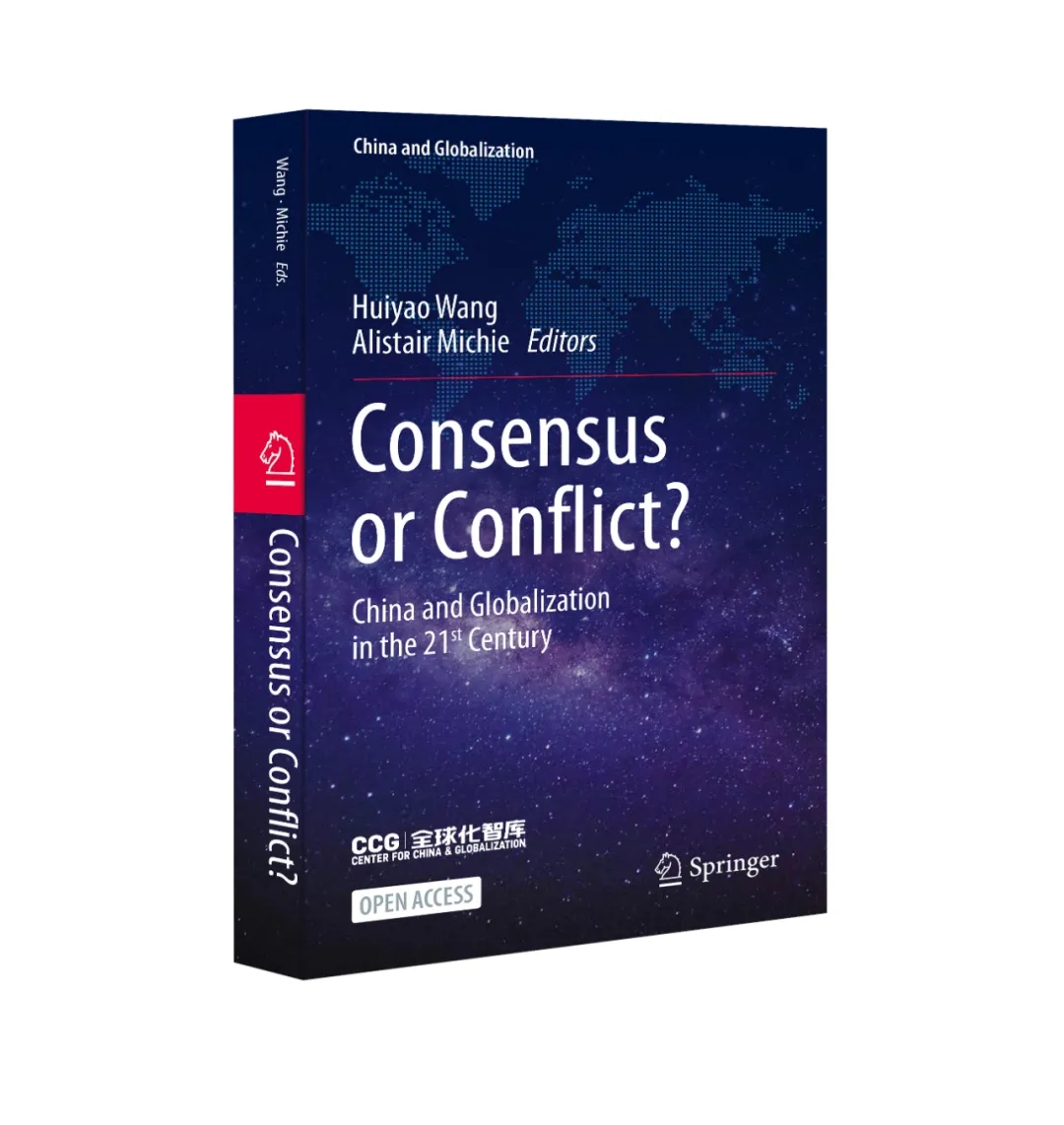

Consensus or Conflict? China and Globalization in the 21st Century, Huiyao Wang and Alistair Michie, editors (on behalf of the Center for China and Globalization). Springer, October 11, 2021; 404 pages; $59.99 hardbound.

A free download of an electronic version is available here:

https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-981-16-5391-9

“Consensus or conflict?” is a hard question to ask in the midst of a trade and technology war between the US and China. The Trump administration imposed a tariff of nearly 20% on most US imports from China and imposed the first-ever technology sanctions with extraterritorial reach, banning sales of semiconductors and the means of manufacturing them from third countries that employ substantial amounts of US technology.

The US persuaded the Dutch government to stop sales of advanced chip lithography equipment to China by ASML – the only manufacturer of extreme ultraviolet machines, which are required to make the most advanced chips.

With a bi-partisan political consensus hostile to China, the Biden Administration has shown no inclination to walk these measures back – although it did rescind one extraterritorial measure, namely the detention of Huawei’s CFO Meng Wangzhou in Vancouver.

It is hard to envision a significant change in the US stance during the next 12 months, when an increasingly unpopular Administration must pull out every stop to maintain its thin majority in Congress.

The US trade representative on October 4 sketched a “new approach to the US-China trade relationship” that contained little new except for a promise to “mitigate the effects of certain Section 301 tariffs that raised costs on Americans.”

Otherwise, the USTR fact sheet focused on “state-centered and non-market trade practices including Beijing’s non-market policies and practices – that distort competition by propping up state-owned enterprises [or] limiting market access – and other coercive and predatory practices in trade and technology.”

Nonetheless, there are good reasons for the United States to rethink its economic stance toward China. US imports from China were 25% higher in August 2021 than in January 2018, when Trump imposed the first round of tariffs.

Inflation represents the biggest risk to the US economy (and to the Democrats’ electoral prospects), and tariffs raise prices for consumers.

The technology boycott has pushed China into an all-country drive for semiconductor self-sufficiency and it is likely to achieve this for all but the most advanced computer chips.

The most pressing concern of the new book’s editors, who did their work under the sponsorship of one of China’s oldest and most influential think tanks, is to help China and the United States talk to each other.

Editor Alistair Michie writes of a “communications crisis” and puts most of the onus on China to improve its mode of address to Americans: “For international messages, China must stop using domestic communication styles, or models, that work well inside China but produce negative communication results outside of China.”

Alistair Michie, co-editor of the new book, is by no means a newcomer to the issues involved. Here he is (second from top left) in a 2012 group photo with China’s newly appointed leader Xi Jinping (front center) and some of Michie’s fellow ‘foreign experts’ meeting at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing. Photro: AFP / Pool / Ed Jones

Without a doubt, China’s current campaigns in public relations are dreadful – but the reader is left to wonder if the problem really lies in mere rhetoric. The real problem, in the view of Harvard’s Graham Allison, is that the United States cannot reconcile itself to the prospect that China will become the world’s most powerful country.

If there is a unifying theme among the several dozen essays that comprise this volume, it is the end of the unipolar world – which was characterized by the American idea of a “rules-based order” – and the emergence of a new set of rules.

Editor Huiyao Wang writes, “The first reality that any new system of global governance must accommodate is that we live in an increasingly multipolar world. The existing US-led system was designed for a world where power was highly concentrated. However, long-term structural trends – in particular the rise of developing countries – mean that in the post-pandemic era no single power will be able to dictate global norms and rules by itself.”

Former US Trade Deputy Representative Wendy Cutler emphasizes China’s bid to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Cutler observes that this “could help reduce China’s reliance on the US market and its vulnerabilities to further tariffs and other sanctions emanating from Washington.

“At the same time,” Cutler adds, “acceding to CPTPP could provide external pressure, similar to the role that World Trade Organization accession played two decades ago, for Beijing to proceed with certain needed domestic reforms, particularly in the services sector.

“Finally, it could be a great public relations coup for Beijing to try to convince the world that it is serious about trade liberalization and structural reform while the US remains hesitant in entering into new trade agreements.”

In fact, Beijing in September applied for CPTPP membership in what Brookings Institution analyst Mireya Solís called “a masterstroke for Chinese diplomacy.”

As Cutler noted, “Twenty years ago, Asia accounted for less than a third of global output. Twenty years from now, Asia will account for more than half the world’s total economy. Today, Asia is home to a burgeoning middle class and a growing and dynamic market” – a market that caters to “many of the countries and companies that will shape the global economy for years to come.”

China, this line of thinking implies, will not attempt to resolve its problems with the United States but rather work around them, concentrating on growing Asian markets and reducing its engagement with a less dynamic America.

That is also the thrust of editors Wang and Michie, who emphasize “policies for changing the ‘rules-based world order’” – that is, an order in which Washington makes the rules. The editors set the tone for the volume with a citation from New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman, whose 2005 book The World is Flat influenced popular views of globalization.

That seems a bit passé. When Friedman’s book appeared, officials of the George W Bush Administration argued with a straight face that US current account deficit at 6% of GDP was benign because it reflected the attractiveness of US investments, and Republican economists suggested that the US should give up manufacturing altogether. Friedman’s flat world has become bumpy in the meantime.

Fully automated robots are shown in August running at high speed at Geely Automobile’s Changxing base in Changxing Economic and Technological Development Zone, in Huzhou City, East China’s Zhejiang Province. Photo: AFP / Tan Yunfeng / Imaginechina

Many of the contributions focus on the structure and governance of international organizations, for example the International Monetary Fund and World Bank. Some contributions are arguments from leaders of the Global South who want a bigger say in these institutions for that part of the world – for example, Shaukat Aziz, a former prime minister of Pakistan.

The most interesting essays address tangible problems of governance in a bumpy world.

Robert Atkinson, the president of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, and his co-author Nigel Cory address what may be the least tractable problem of global governance, namely cross-border data policy. If artificial intelligence is the engine of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, data comprise the fuel – as important to the 21st century as petroleum was to the 20th century. Atkinson and Cory write:

Countries that value a rules-based global digital economy need to come together to enact new global data management rules. It is becoming more and more critical to treat data as the key driver of today’s global economy. Creating new rules will require policymakers to alter their current approaches, which have led to a stalemate in making progress on frameworks for the global internet. China should revise its restrictive approach so that it can play a more constructive role in debates and negotiations between like-minded countries.

Atkinson would like to see a universal internet architecture that supports the seamless flow of data across borders. But there is a formidable obstacle blocking the path to an optimal data policy, namely real and imagined security threats that justify restrictions on data and international data flows:

Policymakers fear that data is being accessed directly through a firm’s in-country facilities or indirectly via extraterritorial requests for data or operations that target data transferred and stored overseas. The 2013 Snowden disclosures about US surveillance were the initial catalyst for policy changes around the world, especially in China and Europe. [In 2013 Edward Snowden leaked a vast amount of secret data from the US National Security Agency.]

The irony is that many of the same Western and democratic countries that denounced US surveillance on the behalf of their citizens have enacted their own surveillance regimes. Furthermore, the debate on national security and data flows is often misleading and disingenuous, as countries use national security in a broad and vague manner to enact restrictions on a growing range of data and digital services that are largely commercial, and not directly tied to national security.

Atkinson shows real courage in assigning blame to both China and the Western democracies, especially the United States, for creating an atmosphere of suspicion. He inveighs against both sides, insisting that they must change their approach:

“The United States needs to move away from an idealist view of digital international relations to a realpolitik one, which is focused more on protecting key economic interests rather than acting as a global ambassador of complete and unfettered internet openness,” he counsels.

“China should revise its restrictive approach to data and digital policies so that it can play a constructive role in debates and negotiations between like-minded countries.”

Sadly, Atkinson’s eminently reasonable suggestions appear unachievable. China has tightened its data security regulations to require strict security reviews for Chinese companies that store data outside the country. A new Chinese law subjects export of data to tight government controls.

Meanwhile, Washington’s stated security grounds for its efforts to suppress Huawei appear to Beijing to be merely a pretext to stop China’s technological advance as a whole.

Innovation-driven growth

Edmund Phelps, the 2006 Nobel Prize Laureate in Economics, offers an upbeat view of China’s prospects:

In any nation where it takes hold, innovation-driven growth is immensely powerful. It transforms the nation from agricultural to industrial, from rural to urban, and from trading to producing. China appears to be on the verge of following this transformative path but cannot be complacent.

Few countries have achieved growth led by indigenous innovation. The kind of social dynamism needed for growth driven by indigenous innovation is rare and easily stifled.

History suggests that dynamic economies are largely sparked by the original ideas of ordinary people using their creativity and imagination and developed by entrepreneurial people alert to new opportunities and keen to start new businesses that develop new concepts into commercial products and methods and then sell them to potential users. This is the China that I hope will emerge.

Phelps elaborated this view earlier this year in a White Paper for Asia Times. Missing from the volume is an equivalent perspective for the United States. America’s lack of dynamism is the main source of its antagonism with China. If America had maintained the pace of innovation that it achieved during the 1980s, when it single-handedly invented the digital economy, China’s footsteps would not echo so ominously behind it.

Museum piece: A wax sculpture of Steve Jobs was displayed with a face mask to draw attention to the Covid-19 pandemic at the Madame Tussauds Wax Sculpture Museum as it reopened its doors to visitors, in Istanbul, Turkey, on July 10, 2020. Photo: AFP / Onur Coban / Anadolu Agency

Two decades ago free traders could argue that China’s growth offered the benefit of cheap products for American consumers, but that view has no purchase today. What is there about today’s China that brings benefits to America, other than a flood of imports? Without a satisfying answer to this question, it is hard to see a reduction in US-China tensions.

“Covid-19 and climate change,” editor Michie writes, together form “the catalyst needed for new, inspired global leadership by the USA and China.” Covid-19, though, remains a source of contention due to disputes over the pandemic’s origin, and global warming is an issue of greater concern to elites of the West than to their voters.

Something more tangible needs to be on the table for the United States and China to perceive a commonality of interest. Robert Atkinson’s discussion of data transfer is both the most relevant economically and the hardest to achieve politically. We appear to be in for more bumps.

From Asia Times, 2021-10-12

[Book Introduction Video]

Download Book at Springer

https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-981-16-5391-9

Browser, Download & Buy Book at Amazon.com:

https://www.amazon.com