【SCMP】 Wang Huiyao: Can we build AIIB into GIIB

April 27 , 2021■ The recovery-boosting infrastructure spending sprees favoured by developed nations are out of reach for less-well-off countries that need them most

■ The AIIB has the scope and track record to expand to a global level and help those nations left behind

High-rise buildings loom over residential houses in central Jakarta in February, 2017. Underinvestment in infrastructure is a chronic problem that predates the pandemic. Photo: AFP

By Wang Huiyao | Founder of the Center for China and Globalization(CCG)

The case for post-pandemic infrastructure spending is compelling. Low interest rates mean states can borrow cheaply to fund projects that spur short-term recovery and long-term economic transformation. No wonder some developed economies have unveiled massive infrastructure plans to revive their economies and “build back better”.

Sadly, this path is closed off to most poorer countries as they lack the fiscal space to build much of anything now. The United Nations is warning of a looming debt crisis for developing countries. Since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, many have hit borrowing limits and 36 have experienced sovereign downgrades.

Underinvestment in infrastructure is a chronic problem that predates the pandemic. The world faces an infrastructure financing shortfall of US$18 trillion out to 2040.

As the global economy struggles to recover, it is time to consider forming a new institution to address this gap. The world needs a dedicated global infrastructure bank that can mobilise capital to spur recovery and build for long-term goals related to climate, resilience and inclusivity.

Built from scratch, such a bank would need many years to be fully operational. However, there is one candidate well placed to expand and take on this mission: the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB).

In the past six years, the AIIB has established itself as an effective multilateral development bank (MDB). Having attracted several advanced economies as members and adopted the high standards of other MDBs, it has gained recognition from organisations such as the UN and AAA ratings from ratings agencies.

The AIIB’s scope has grown far beyond Asia. It finances projects in Africa and Latin America and has more than 100 members across the world. With a fresh capital injection and expanded membership, the bank could expand its remit and become the Global Infrastructure Investment Bank(GIIB).

This would involve removing the 75 per cent requirement for regional shareholding and investment, and inviting new members to play major roles – notably the US and Japan – as well as getting more countries in other regions to join. In addition, it could form a special body for multilateral actors including MDBs and regional organisations to enhance global coordination between existing infrastructure initiatives.

To succeed, the Global Infrastructure Investment Bank would need a clearly defined mission. Three areas stand out.

The first is sustainable infrastructure. Making the wrong investments during the post-pandemic recovery could lock countries into carbon-intensive development paths. Aligning investment with climate goals would be central to the new bank.

The second is inclusive connectivity, in particular closing the digital divide. The pandemic has driven online forms of work, study and business. However, 3.7 billion people still lack internet access. The new bank could take a lead in digital infrastructure financing.

The third priority would be mobilising private capital. With public finances limited during the pandemic, innovative financing models are needed to encourage private sector involvement. The AIIB is already focusing on this with a goal to boost the share of private financing to 50 per cent by 2030.

Some might question the need for a new multilateral development bank when others already exist. However, it could add unique value while complementing the work of other institutions.

The World Bank and other multilateral development banks also fund infrastructure, but they already have stretched balance sheets and have shifted their focus to other initiatives. By contrast, the Global Infrastructure Investment Bank could focus solely on infrastructure.

A little overlap is not a bad thing. The AIIB has brought fresh impetus to development financing since its launch, and its innovations have put pressure on other banks to raise their game.

This has prompted the Asian Development Bank to slash its approval cycles. The World Bank and ADB have raised capital resources and adjusted lending practices to stay relevant.

The new bank would be designed to complement existing MDBs, not compete with them. The AIIB pursues a collaborative model, and most of its projects have been co-financed with other multilateral development banks. It could further develop this model and find new ways to co-finance, share expertise and work with other organisations.

This collaborative role has grown more important with the proliferation of integration efforts at the national and regional level that do not always mesh well. The Global Infrastructure Investment Bank could be a multilateral platform to enable long-term planning and coordination, promoting intra- and inter-regional connectivity in a cost-effective manner.

Despite the strong case for a global infrastructure bank, some in the West might oppose any such China-backed initiative. This was Washington’s reaction when the AIIB was launched.

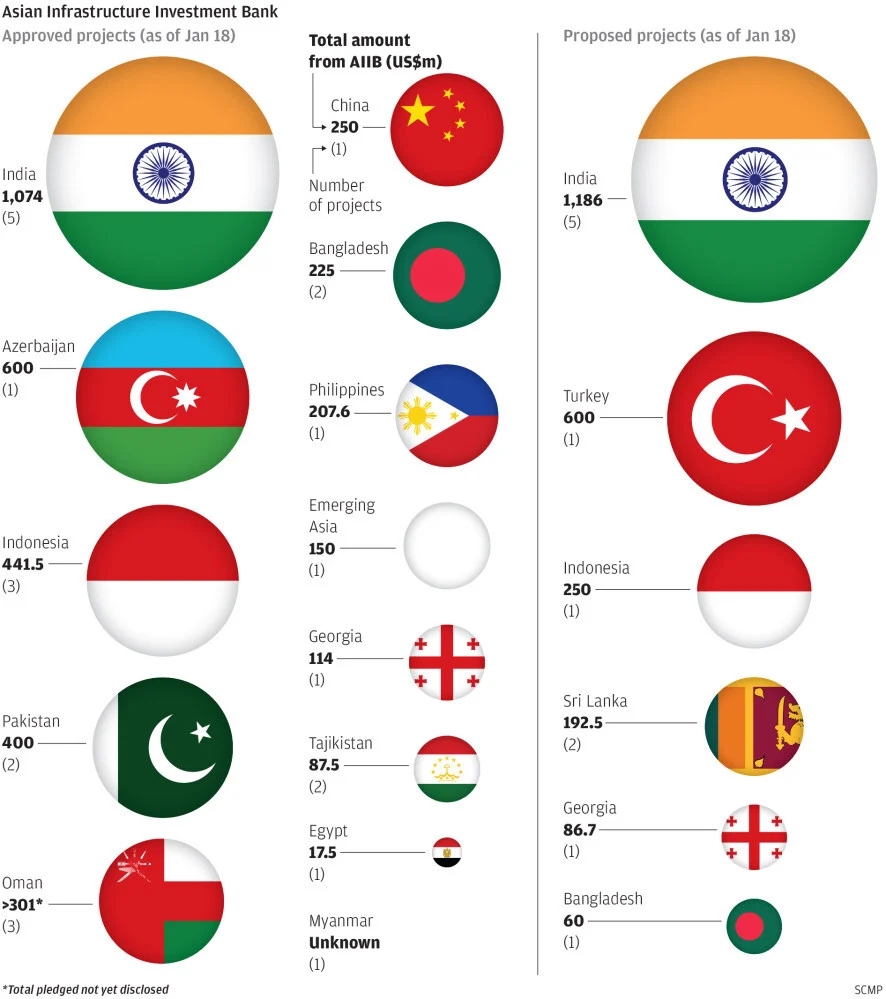

Those worried that the new bank would be used for geopolitical ends should examine the AIIB’s multilateral structure and track record. The largest beneficiary of AIIB lending is India, arguably China’s foremost regional rival and not a participant in the Belt and Road Initiative.

China has the experience and resources to make valuable contributions to global public goods in infrastructure. The AIIB can create effective multilateral institutions and provide a ready-made framework for a new global infrastructure bank, but US participation would be essential to realise its true potential.

Getting Western countries to work with China on such a venture might seem like a tall order, but the high stakes in ensuring a green, inclusive post-pandemic recovery call for bold action. As rich countries dole out trillions for infrastructure at home, they should be open to ideas that help less-fortunate nations “build back better”, too.

From scmp.com, 2021-4-27

Topical News See more