【China Daily】What do you remember of the life-changing gaokao?

June 07 , 2017Every Chinese person knows about the gaokao. Just mention the national college entrance exam in a crowded room and watch as people recall the tears, smiles and hard work they endured.

For those of us who’ve took the exam, the experience is carved deep into our hearts. We remember trying our very best to chase our dreams.

This year, more than 9 million exam candidates are sitting the gaokao between June 6-7. To cheer them on, we asked some college students for their gaokao memories.

For most Chinese, the test can be treated as a “turning point” which ordinary people can change their lives. Millions of students have sat the exam since 1977 and each has their own story to tell, encompassing both success and failure, laughter and regrets.

Older memories

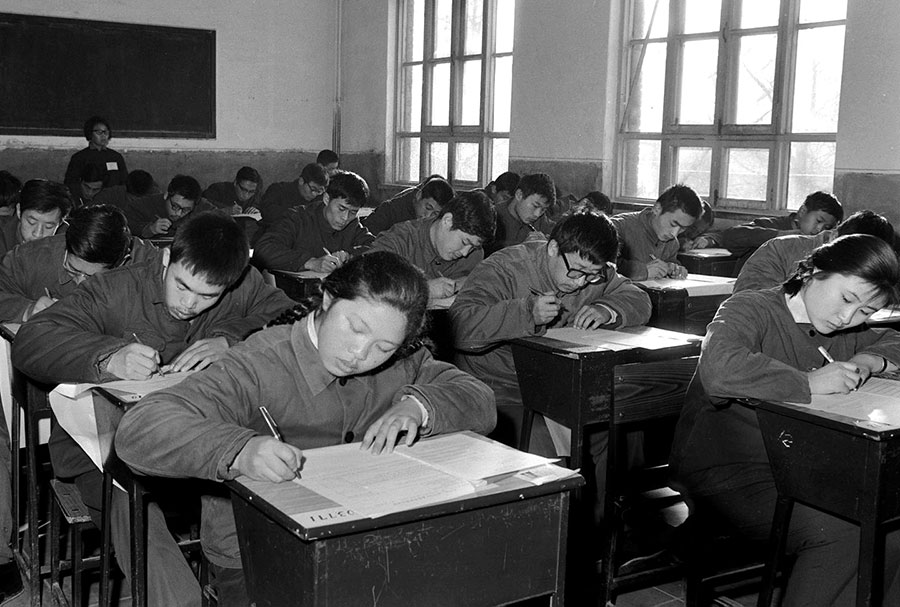

The 1977 exam is notable for two things: first, it was the only gaokao to be held during winter, not summer as is customary; and second, it resulted in the lowest acceptance rate since the 1952 creation of the gaokao and its related admissions system. Just 5 percent of examinees were granted places at colleges.

Now, let’s look back on stories of the Class of ’77 and trace their memories of the event that changed their lives.

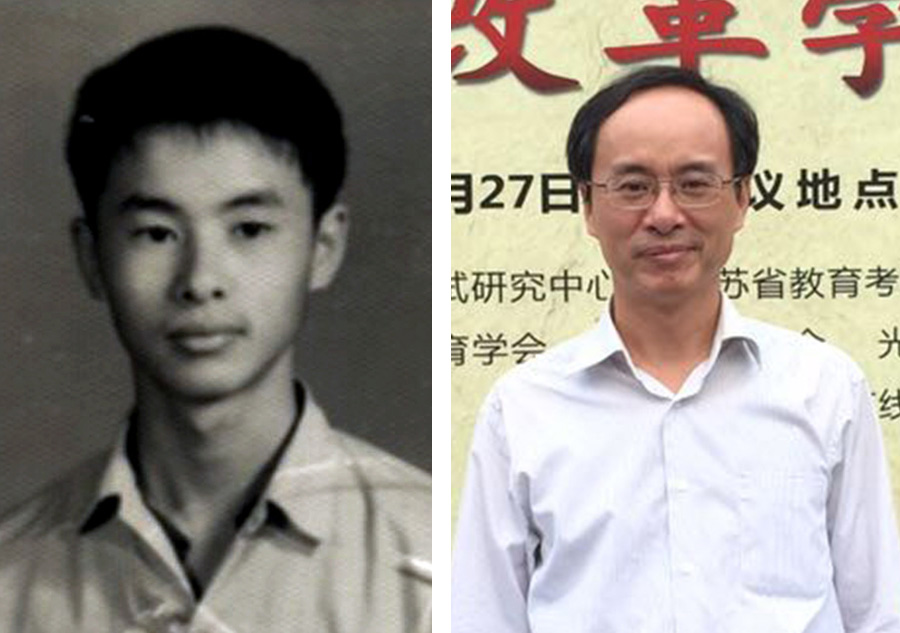

Liu Haifeng

Director of the Institute of Education at Xiamen University

Liu, a renowned gaokao researcher, is grateful for the chance he was given, calling the experience “a historical coincidence”.

For him, the revival of the exam was not just a hugely significant event for the examinees, but also a turning point for China.

“

“Later, many became well-known figures and pillars in all walks of life, and they played key roles in China’s reform and opening-up, laying a firm foundation for the country’s economic takeoff and today’s prosperity,

”

In the winter of 1977, the then-18-year-old hopeful was one of 5.7 million people who walked into exam halls nationwide to take the first gaokao given in more than 10 years, after it was suspended during the “cultural revolution” (1966-76).The exam is China’s foremost method of selecting academic talent, and one of the most important ways by which ordinary people can change their lives.

The 1977 exam is notable for two things: first, it was the only gaokao to be held during winter, not summer as is customary; and second, it resulted in the lowest acceptance rate since the 1952 creation of the gaokao and its related admissions system. Just 5 percent of examinees were granted places at colleges.

Liu was among the lucky ones. He had applied to study Chinese literature at Fujian Normal University, but after passing the exam he was unexpectedly offered a place in the history department at Xiamen University in his hometown in Fujian province. That offer set Liu on a decadeslong path of teaching and research at the prestigious establishment.

Even today, Liu, a renowned gaokao researcher, is grateful for the chance he was given, calling the experience “a historical coincidence”.

For him, the revival of the exam was not just a hugely significant event for the examinees, but also a turning point for China.

“The gaokao in 1977 and the following two years selected about 1 million talents, who are called ’the new three classes’ (of 1977, 1978 and 1979). Later, many became well-known figures and pillars in all walks of life, and they played key roles in China’s reform and opening-up, laying a firm foundation for the country’s economic takeoff and today’s prosperity,” said Liu Haifeng, director of the Institute of Education at Xiamen University.

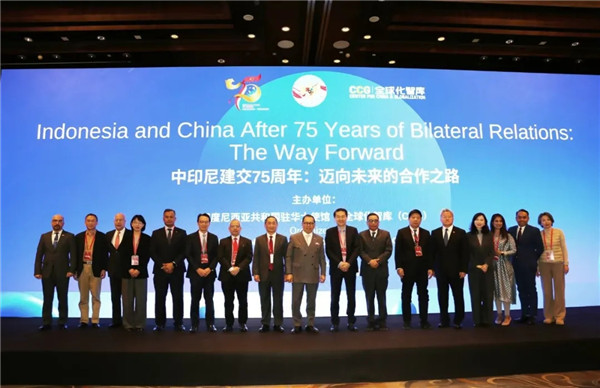

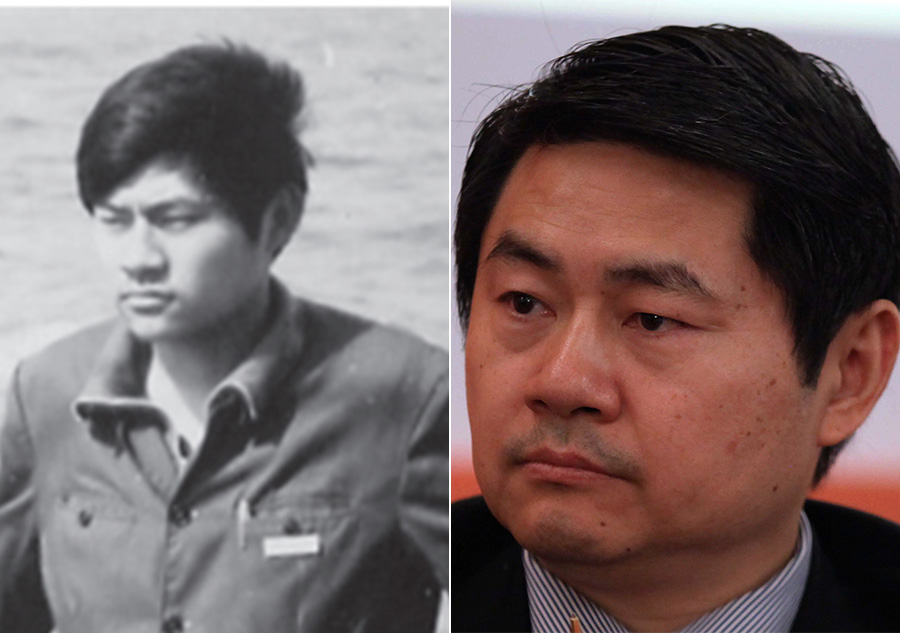

Wang Huiyao

President of CCG

“I was so excited, knowing that it was an opportunity to change my life.”

– Wang Huiyao, director of a think tank called the Center for China and Globalization(CCG), chairman of the China Global Talents Society and a consultant to the State Council

In October 1977, when the news was announced that the exam would be resumed, Wang Huiyao had spent almost a year and a half as a farm laborer. He was a zhiqing, a “sent-down youth”, in a village 30 kilometers from his hometown, Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan province in China’s southwestern region.

“I was so excited, knowing that it was an opportunity to change my life,” he said.

Having passed the exam, Wang studied English and American Literature at Guangdong University of Foreign Studies in Guangzhou, Guangdong province. After graduation, he became an official at the Ministry of Commerce.

In 1984, he traveled to Canada to study for a master’s and a doctorate in business administration, and then worked in senior positions for a number of large companies. In the mid-1990s, he returned to China and started several businesses.

Now, as director of a think tank called the Center for China and Globalization(CCG), chairman of the China Global Talents Society and a consultant to the State Council, China’s Cabinet, Wang sees the 1977 revival of the exam as the starting point of all his rich, horizon-expanding experiences.

“

“If not for the gaokao that year, none of those things would have happened,

”

Maintaining momentum

During the “cultural revolution” (1966-76), many graduates of junior middle schools and high schools – at least 16 million according to official records – in cities were sent to villages as part of the “down to the countryside” movement.

In October 1977, when the news was announced that the exam would be resumed, Wang Huiyao had spent almost a year and a half as a farm laborer. He was a zhiqing, a “sent-down youth”, in a village 30 kilometers from his hometown, Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan province in China’s southwestern region.

For Wang, then age 19, gaokao was a distant and irrelevant word. When the exam was suspended in 1966, it was replaced by a college admissions policy that relied solely on recommendation. That meant only workers, farmers and soldiers were selected to attend college, irrespective of academic achievement or lack of it.

Wang, born and raised in a large city, quickly found life difficult and disappointing: he “cohabited” with mice in a thatched cottage that lacked electricity, sanitation or hot water; worked from 5 am to 10 pm every day; walked barefoot along muddy lanes on rainy days; and drank water boiled with chilies to keep warm in winter.

“At the time, I couldn’t understand why people across the world were trying to move from rural areas to cities for better lives, but our mobility went in totally the opposite direction,” said Wang, who is now an adviser on policies related to spotting talent both at home and abroad.

“However, I had a strong feeling that such an abnormal situation wouldn’t last long. I knew the gaokao would be revived sooner or later, but didn’t know exactly when.”

With that belief, Wang studied at night, reading all the books available to him and learning English by listening to radio programs.

When the announcement he had waited for finally arrived, it was earlier than anticipated. On the evening of Oct 12, Wang heard on the village broadcast system that the exam would be revived and held in mid-December.

“I was so excited, knowing that it was an opportunity to change my life,” he said.

Having passed the exam, Wang studied English and American Literature at Guangdong University of Foreign Studies in Guangzhou, Guangdong province. After graduation, he became an official at the Ministry of Commerce.

In 1984, he traveled to Canada to study for a master’s and a doctorate in business administration, and then worked in senior positions for a number of large companies. In the mid-1990s, he returned to China and started several businesses.

Now, as director of a think tank called the Center for China and Globalization, chairman of the China Global Talents Society and a consultant to the State Council, China’s Cabinet, Wang sees the 1977 revival of the exam as the starting point of all his rich, horizon-expanding experiences.

“If not for the gaokao that year, none of those things would have happened,” he said.

Chilblains and classes

In 1977, Tang Min was a 24-year-old math teacher at a middle school in Nanning, the capital of the Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region. He took the exam together with his students and was admitted by the math department of Wuhan University in Hubei province.

“Twenty-five was the upper age limit for examinees that year, and I was already 24. I treated it as my last opportunity to take the exam, so I seized every minute, trying to make the best preparations,” said Tang, now a macroeconomic researcher and a State Council consultant.

Because the gaokao had been suspended for a about decade, large numbers of people who should have already taken it flocked to sit the exam, leading to a glut of examinees in the first few years after it was revived.

In addition to teachers and students sitting the exam together, siblings of different ages took the exam at the same time.

Liu Haifeng and his younger brother prepared for the exam in the 6-square-meter bedroom they shared. They had just two months for revision.

“Our families, particularly our parents, showed full support. My brother and I were exempted from housework so that every minute could be saved for study,” he said.

Students such as Liu, who planned to pursue arts-based academic paths at college, were tested in four subjects, similar to today’s gaokao: Chinese, math, politics, and a combination of history and geography.

Chinese was Liu’s strength, so he didn’t need much preparation, but math, history and geography were his weak points because those subjects weren’t taught when his generation was at high school. He had to learn from scratch, using outdated, poorly printed textbooks, the only learning materials available at the time.

“It was during the prep that I learned the names of many national capitals for the first time. For example, I learned that Budapest is the capital of Hungary – I hadn’t known those things before.”

He recalled that almost all middle schools offered free classes to help examinees learn and review lessons.

“So many people came to the classes that the lecture rooms were unable to hold them all, resulting in some having to stand outside at the window to listen to the teachers,” he said.

“However, no one complained. It seemed as though everyone was filled with energy and hope, and thirsty for knowledge. The atmosphere was really fantastic,” he said, adding that although he often had chilblains on his hands during the harsh winter, he doesn’t remember feeling cold.

Retrospective

According to Wang Huiyao, a member of the Class of ’77 who now runs a think tank that formulates policies related to spotting talents, things often become clearer when people look back.

“Compared with a lot of young people who had spent three, five or even 10 years working in the countryside, I was really lucky because I was young and had only recently left school. That meant I still had a sense of learning when the gaokao was revived,” he said.

“If the exam had been revived a few years later, perhaps the learning abilities of people my age would have been weakened by the long days of farm work, and we may have missed out on the opportunity to attend college.”

He said students who passed the gaokao in 1977 and the years that followed were the executors of the reform and opening-up policy, and they benefited by becoming senior officials and influential figures during the process.

Now that many of them have turned 60 and have retired, he feels it’s time to look back, sum up and leave a legacy.

To do that, he compiled a book, The Three Classes of 1977 to 1979: Memories of Chinese College Students. Published in 2014, the book invited 38 outstanding students from the “new three classes” – including the writer Liu Zhenyun, Xu Xiaoping, cofounder of the New Oriental Education & Technology Group, and Chen Pingyuan, professor of Chinese literature at Peking University – to tell their stories.

Wang plans to publish an updated version of the book later this year. He has invited members of the “three new classes” to share their experiences and commemorate the 40th anniversary of an epochal event in their lives.

Tang Min said members of the Class of 1977 and even those of 1978 and 1979 are special, but their achievements should not be exaggerated.

In his opinion, though many people from the group became elites in many walks of life in China, very few became world-famous scholars or successful enterprisers.

“I think we serve as a link between the past and the future; we are more like the forerunners or pathfinders, pushing forward reform and opening-up along with China’s social and economic development,” he said.