Takers of first gaokao warn robots may replace workers

June 22 , 2017

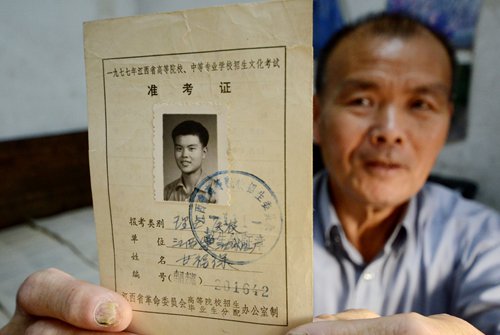

Gan Fubao, 70, from Nanchang, East China’s Jiangxi Province, shows his admission ticket for the 1977 college entrance examination. Gan entered Nanchang University that year, as one of the first university students in the country after the examination resumed. From 1978 to 2016, Gan bought the exam papers every year and answered them at home. Photo: CFP

Xu Xiaoping, now a 61-year-old angel investor, recalled at a seminar commemorating the 40th anniversary of the resumption of the gaokao, China’s national college entrance examinations, organized by the Center for China and Globalization (CCG)

When he first heard that he might get into a university for workers, peasants and soldiers, the then 21-year-old Xu Xiaoping was thrilled.

But soon he was turned down because the local education commission chief in his hometown of Taixing, East China’s Jiangsu Province did not like him because the young man had a sweetheart.

“He considered my love to be puppy love. A young man’s future was simply decided by the whims of a local education commission chief,” Xu, now a 61-year-old angel investor, recalled at a seminar commemorating the 40th anniversary of the resumption of the gaokao, China’s national college entrance examinations, organized by the Center for China and Globalization (CCG) over the weekend.

During the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), the gaokao system was cancelled and replaced by a recommendation system in which only workers, peasants and soldiers could access higher education, and even then only after strict political and family background checks. Millions of high school students in China had no opportunity to continue their campus life for over a decade.

“The incident brought me a deep understanding of the Cultural Revolution, which blocked the path to both my love and future,” Xu said.

Fortunately, Xu was able to be among the very first batch of college students after the gaokao was reinstated in 1977. His personal development and that of his peers was closely connected to the fate of the country, as they experienced, participated in and boosted China’s reform and opening-up, which was launched in 1978.

The first gaokao-takers since its resumption had their fate rewritten thanks to the renewed opportunities opened to them, but 40 years later, many of them are disappointed by the country’s lagging education system.

Special candidates

“Most of the candidates had already been soldiers, peasants or workers before they took the gaokao in 1977, a unique phenomenon that never happened in the following years,” Qian Yingyi, dean of the School of Economics and Management at Tsinghua University who sat the gaokao in 1977 and was then admitted by Tsinghua, said at the seminar.

Qian, along with millions of other “educated youths,” was relocated from an urban area to remote areas as part of the “Up to the Mountain and Down to the Countryside” movement initiated by then Chinese leader Mao Zedong.

The tough living conditions they endured meant they had to prepare for the gaokao all by themselves.

Middle schools nationwide suspended classes and universities barely admitted new students during the Cultural Revolution, so by 1977, tens of millions of junior and senior middle school students had not attended school for a decade.

This resulted in a huge age gap among the first group of college students, with the youngest at around 15 and the oldest in their mid-30s.

In the winter of 1977, about 5.7 million candidates took the gaokao, but only 270,000 of them were admitted the next spring. The admission rate of first gaokao – only 4.7 percent – was lower than that in any of the 40 years since.

The fate of the first group of college students was shaped by China’s reform and opening-up drive initiated by top leader Deng Xiaoping.

A majority of the 30 experts attending the CCG seminar were later sent to study in the US after Beijing and Washington established diplomatic ties in 1979.

The resumption of the gaokao marked the coming of a new era that highlighted talent, and also marked China’s transformation from chaos to stability and from stressing one’s family background to acknowledging that knowledge can change one’s fate, according to CCG.

Beat robots

Relying as it does on rote learning, the gaokao is an overly rigid talent selection system that is in dire need of change, said Shao Hong, deputy president of the Central Institute of Socialism, at the seminar.

“Current gaokao reforms are not ideal as changing exam questions and designating times candidates can take exams cannot alter the excessive competition brought by the gaokao,” Shao said.

Millions of candidates fight to get enrolled by the few national-level and provincial universities which are allocated sufficient education resources, such as funding, high-quality teachers and equipment, according to Shao.

China should clear away unnecessary approval procedures for building schools and support the development of new education patterns such as private universities, online universities and homeschools, Shao said.

However, gaokao reform should not be conducted only at universities; instead, China needs to redesign its whole education system from top to bottom, said Tang Min, vice president of the Youchange China Social Entrepreneur Foundation and councillor of the State Council, told the seminar.

“If China cannot establish a low-cost and highly efficient lifelong education system, we will soon be replaced by robots,” Tang said. (By Zhang Hui)